Stefan G. Hofmann, Ph.D., David A. Spiegel, M.D.

advertisement

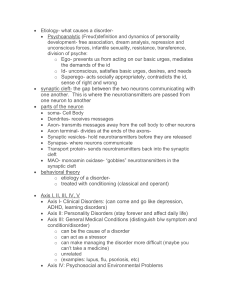

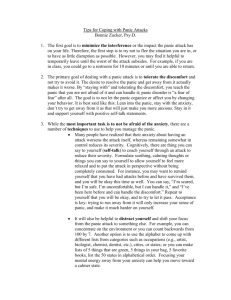

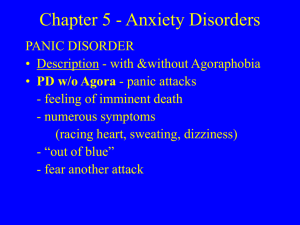

Special Articles JHofmann Anxiety Psychother and SG,Panic; Pract Spiegel Res Agoraphobia; DA: 1999; Panic 8(1):3–11 control Cognitive-Behavioral treatment and its Therapy applications. Panic Control Treatment and Its Applications Stefan G. Hofmann, Ph.D. David A. Spiegel, M.D. Panic Control Treatment (PCT) is a widely used, empirically validated cognitive-behavioral treatment for panic disorder. Initially developed for the treatment of panic disorder with limited agoraphobic avoidance, PCT more recently has been finding broader applications. It has been used as an aid to pharmacotherapy discontinuation in panic disorder; in the treatment of panic attacks associated with other disorders such as schizophrenia; and, in combination with a situational exposure component, in the treatment of patients with moderate to severe agoraphobia. The authors critically review the evidence for the clinical efficacy of PCT and recent work directed at further enhancing the long-term efficacy and cost-effectiveness of treatment. (The Journal of Psychotherapy Practice and Research 1999; 8:3–11) S ince panic disorder was formally recognized as a discrete entity in DSM-III, it has become one of the most intensively studied anxiety disorders. By definition, panic disorder causes significant distress or interference with the individual’s life, exacting substantial personal costs. In addition, the disorder imposes high direct and indirect costs on the nation in medical resources used for care, treatment, and rehabilitation and in reduced or lost productivity.1 A growing body of evidence supports both the efficacy and effectiveness (clinical utility) of psychosocial interventions for panic disorder. For example, a recent meta-analysis of 43 controlled studies found that cognitive and cognitive-behavioral treatments, collectively, had a higher mean treatment effect size and a lower attrition rate than pharmacological treatments.2 In addition, evidence is beginning to appear from naturalistic studies that cognitive-behavioral therapy for panic disorder may be more cost-effective than pharmacotherapy, even within the first treatment year.3 Yet despite the demonstrated efficacy and favorable cost profile of cognitive-behavioral therapy for panic disorder,4 most patients treated in clinical practice settings do not receive it.5–7 That situation is due in large part to two problems: limited knowledge by physicians and the general public about the nature and benefits of Received June 22, 1998; revised August 27, 1998; accepted September 1, 1998. From the Department of Psychology, Boston University, and the Center for Anxiety and Related Disorders at Boston University. Address correspondence to Dr. Hofmann, Center for Anxiety and Related Disorders at Boston University, 648 Beacon Street, 6th Floor, Boston, MA 02215. Copyright © 1999 American Psychiatric Press, Inc. J Psychother Pract Res, 8:1, Winter 1999 3 Panic Control Treatment and Its Applications cognitive-behavioral therapies, and the lack of an effective means for disseminating new treatments, resulting in reduced treatment availability.8 The present article provides an overview of one of the most well-studied forms of cognitive-behavioral therapy for panic disorder, Panic Control Treatment (PCT),9,10 and reviews the evidence for its efficacy. Also reviewed is some recent work directed at extending the application of PCT to new populations and enhancing its long-term efficacy and cost-effectiveness. DESCRIPTION OF TREATMENT The general goal of PCT is to foster within patients the ability to identify and correct maladaptive thoughts and behaviors that initiate, sustain, or exacerbate anxiety and panic attacks. In service of that goal, the treatment combines education, cognitive interventions, relaxation and controlled breathing procedures, and exposure techniques. It is usually delivered in 11 or 12 weekly sessions, either individually to patients or in a small group format. The PCT protocol includes a variety of information and skill-building components.10 In early sessions, patients are taught about the nature and function of fear and its nervous system substrates. The fear response is presented as a normal and generally protective state that enhances our ability to survive and compete in life. Panic attacks are conceptualized as inappropriate fear reactions arising from spurious but otherwise normal activation of the body’s fight-or-flight nervous system. Like other fear reactions, they are portrayed as alarms that stimulate us to take immediate defensive action. Because we normally associate fight-or-flight responses with the presence of danger, panic attacks typically motivate a frantic search for the source of threat. When none is found, affected individuals may look inward and interpret the symptoms as signs that something is seriously wrong with them (e.g., “I’m dying of a heart attack,” “I’m losing my mind”). In addition to normalizing and demystifying panic attacks, the educational component of PCT provides patients with a model of anxiety that emphasizes the interaction between the mind and body and provides a rationale and framework for the skills to be taught during treatment. A three-component model is used, in which the dimensions of anxiety are grouped into physical, cognitive, and behavioral categories. The physical component includes bodily changes (e.g., neurological, hormonal, cardiovascular) and their associated somatic sensations (e.g., shortness of breath, palpitations, light4 headedness). The cognitive component consists of the rational and irrational thoughts, images, and impulses that accompany anxiety or fear (e.g., thoughts of dying, images of losing control, impulses to run). The behavioral component contains the things people do when they are anxious or afraid (e.g., pacing, leaving or avoiding a situation, carrying a safety object). Most important, these three components are described as interacting with each other, often with the result that anxiety is heightened. Having laid this foundation, PCT then teaches patients skills for controlling each of the three components of anxiety. To manage some of the physical aspects of anxiety, such as sensations due to hyperventilation (e.g., lightheadedness and tingling sensations) or muscle tension (e.g., trembling and dyspnea), patients are taught slow, diaphragmatic breathing or progressive muscle relaxation. To reduce anxiety-exacerbating thoughts and images, patients are taught to critically examine, on the basis of past experience and logical reasoning, their estimations of the likelihood that a feared event will occur, the probable consequences if it should occur, and their ability to cope with it. In addition, they are helped to design and conduct behavioral experiments to test their predictions. To change maladaptive anxiety and fear behaviors, patients are taught to engage in graded therapeutic exposure to cues they associate with panic attacks. The exposure component of standard PCT (called interoceptive exposure) focuses primarily on internal cuesspecifically, frightening bodily sensations. During exposure, patients deliberately provoke physical sensations like smothering, dizziness, or tachycardia by means of exercises such as breathing through a straw, spinning, or vigorous exercise. These exercises are done initially during treatment sessions, with therapist modeling, and subsequently by patients at home. As patients become less afraid of the sensations, more naturalistic activities are assigned, such as drinking caffeinated beverages, having sexual intercourse, or watching scary movies. Exposure to external cues (traditional situational exposure) is not systematically addressed in standard PCT, although as patients begin to apply the techniques they have learned, they are encouraged to gradually reenter situations they have been avoiding. The developers did not include a more systematic situational exposure component in PCT because they wanted to focus initially on the experience of panic attacks, rather than on avoidance behavior, since this had not been done previously. An optional agoraphobia supplement was developed later, J Psychother Pract Res, 8:1, Winter 1999 Hofmann and Spiegel for use with patients who have significant situational avoidance.11 EFFICACY OF PCT The practice guidelines published by the American Psychiatric Association concluded that pharmacotherapy and cognitive-behavioral therapy are the first-line treatments for panic disorder.4 Moreover, PCT is classified as a “well-established” intervention for panic disorder by the Task Force on Promotion and Dissemination of Psychological Procedures of the American Psychological Association, Division of Clinical Psychology.12 For a treatment to be classified as “well-established,” the following criteria had to be met: first, the efficacy of the intervention had to be demonstrated in at least two clinical trials conducted by different investigators or in a large series of well-designed single case studies; second, treatment had to be delivered in accordance with a manual; third, the characteristics of the subject sample had to be clearly delineated; and fourth, the treatment had to be either as efficacious as an already established treatment or superior to a placebo or other treatment. The efficacy of PCT for the treatment of panic disorder with limited agoraphobia has been demonstrated in numerous clinical trials. In an early study, PCT was found to be superior to a waitlist condition and a relaxation condition.9 In an intent-to-treat analysis, approximately 80% of patients assigned to PCT were panic free at posttreatment, compared with 40% of patients assigned to applied relaxation and 30% of waitlist patients. Similar results were reported by Klosko and colleagues,13,14 who demonstrated that PCT was superior to either the waitlist or drug placebo as well as alprazolam in the treatment for panic disorder. The authors found that 87% of patients in the PCT group were panic free by the end of treatment, compared with 50% in the alprazolam condition, 36% in the placebo group, and 33% in the waitlist group. A 2-year follow-up of PCT completers found that gains were maintained.15,16 Subsequently, Telch et al.17 found that a treatment similar to PCT was effective when administered in an 8-week group therapy format. At posttreatment, 85% of PCTtreated patients were panic free, versus 30% in a waitlist condition. When a more stringent outcome criterion was used, including measures of panic frequency, general anxiety, and agoraphobic avoidance, 63% of PCTtreated patients and only 9% of waitlist subjects were classified as improved. J Psychother Pract Res, 8:1, Winter 1999 Most recently, M. Katherine Shear at the University of Pittsburgh, Jack M. Gorman at Columbia University, Scott Woods at Yale University, and David H. Barlow at our center at Boston University compared PCT to imipramine, a pill placebo, and combinations of PCT with imipramine or a pill placebo. The results from that study suggest that PCT was comparable to imipramine on nearly all measures during treatment, with better maintenance of gains after treatment discontinuation.18 Furthermore, the results showed that more than one-third of all eligible patients refused participation in the study because they were unwilling to take imipramine.19 In contrast, only 1 out of 308 potential participants refused the study because of the possibility of receiving psychotherapy.19 ACTIVE INGREDIENTS OF PCT PCT consists of a combination of cognitive and behavioral treatment components, including education, cognitive restructuring, breathing retraining or relaxation, and interoceptive exposure. It is not known at present whether all of those components contribute uniquely to the efficacy of the treatment. Good outcomes have been reported for related treatments that differ in their emphasis on the components of PCT.20–22 Direct comparisons of the various components of PCT are lacking, but some case studies23 and the aforementioned meta-analysis of panic disorder treatment studies2 provide some indirect data relating to active ingredients. Among the psychosocial treatments studied, therapies incorporating both cognitive restructuring and interoceptive exposure had the highest overall mean effect size (ES = 0.88, 7 studies). Only three studies evaluated cognitive interventions alone as treatment, and the results were varied, with effect sizes ranging from –0.95 to 1.10 (mean ES = 0.18). However, other studies suggest that a combination of interoceptive exposure and cognitive restructuring is not significantly more effective than either treatment alone.21,24 Until further information is available, the relative importance of the elements of PCT remains unclear. LIMITATIONS OF EXISTING TREATMENT STUDIES Although no other type of psychosocial intervention has been shown to be more effective for panic disorder than PCT, several limitations of existing studies necessitate 5 Panic Control Treatment and Its Applications care in interpreting published efficacy data. First, as noted earlier, most studies of PCT have enrolled panic disorder patients with little or no agoraphobia. The efficacy of PCT for patients with greater degrees of agoraphobia is largely unknown, but it is probably lower than for less avoidant patients. Second, even in samples with little or no agoraphobia, panic-free rates generally are higher than response rates based on more global measures of improvement. For example, in the Telch et al. study,17 although 85% of patients were panic free at posttreatment, only 63% met a more stringent response criterion including measures of general anxiety and agoraphobic avoidance. Similarly, a study of subjects treated with variations of PCT at our center found that 68% were panic free 3 months posttreatment, but only 40% met broader criteria for high endstate functioning.25 Third, the efficacy data from nearly all treatment studies to date have been based on cross-sectional assessments. Although such assessments show good maintenance of gains on average following cognitive-behavioral therapy, longitudinal data reveal that many patients have a fluctuating posttreatment course, with periods of symptom recrudescence. For example, in the Brown and Barlow study,25 40% of subjects met criteria for high endstate functioning at 3 months posttreatment and 57% at 24 months posttreatment, but only 27% met the criteria at both 3 and 24 months. These findings indicate that there still is room for improvement in PCT and similar cognitive-behavioral interventions for panic disorder. Fourth, it is uncertain how PCT compares with some of the more recently investigated pharmacotherapies, such as selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors. Most of the comparative treatment outcome studies have used “older” medications, such as imipramine, thus limiting the generalizability of the results. MODIFICATIONS TO PCT In recent years, clinicians and researchers have begun to experiment with variations of PCT. Some modifications, such as combining PCT with situational exposure, including significant others in treatment, or adding a relapse prevention component, are intended to extend the applicability of the treatment or improve its long-term outcome. Others, such as administering PCT in abbreviated or self-help formats, are intended to improve the cost-effectiveness of treatment or make it more accessible to patients. 6 Combining PCT With Situational Exposure When PCT initially was developed, the necessary and sufficient criterion for the diagnosis of panic disorder was the presence of a minimum number of panic attacks within a specified period of time. Psychosocial treatments at the time (e.g., relaxation therapies and situational exposure) tended to focus on general arousal and tension or situational avoidance. PCT differed in that it specifically targeted patients’ experiences of panic attacks and anticipatory anxiety. Consistent with that focus, trials of PCT were conducted among patients for whom panic attacks were the principal problemthat is, patients having limited agoraphobic avoidance. As discussed earlier, the treatment was very effective in eliminating attacks in that group. However, other measures indicated that despite being panic free, some patients continued to evidence functional impairment, largely owing to residual agoraphobic avoidance. Presumably that would have been even more the case if patients having more marked agoraphobia were included. To address that problem, clinicians often combine PCT with in vivo situational exposure assignments,11 which require patients to systematically enter anxietyprovoking situations and stay there until their anxiety subsides. Although such combinations have not been well studied, clinical experience and what empirical evidence there is suggest that this approach is effective. For example, several investigators have reported good results with combinations of exposure therapy and cognitive interventions like those used in PCT.26–32 Recently, we have been experimenting with the combination of PCT and brief (2 or 3 days) massed exposure for treating panic disorder patients with moderate to severe agoraphobia. Preliminary results are encouraging.33 Including Significant Others in Treatment As a result of early clinical observations that the interpersonal systems of individuals with panic disorder and agoraphobia may be disrupted by treatment interventions,34 some researchers have tried including significant others in treatment. Although the original observations have not been supported consistently,35 data do suggest that inclusion of family members in treatment may enhance the efficacy of PCT and related psychosocial treatments, particularly exposure therapy. For J Psychother Pract Res, 8:1, Winter 1999 Hofmann and Spiegel example, Barlow and colleagues36,37 found that including significant others in exposure therapy significantly improved the outcome at posttreatment and at both 12- and 24-month follow-ups. Additionally, the inclusion of spouses in treatment for panic disorder and agoraphobia (including PCT) has been associated with improvement in marital satisfaction.37–40 Advantages also have been found for the involvement of mothers in the treatment of adolescents with agoraphobia. 41 Adding Relapse Prevention Strategies To further improve the long-term outcome of PCT, we currently are experimenting with the inclusion of a relapse prevention component, the goal of which is to teach patients to anticipate and respond constructively to setbacks that might occur after treatment has ended. Interventions like these have been shown to be helpful in various psychiatric disorders.42–44 Other strategies also may be useful. For example, in a recent case at our center, the use of psychophysiological recording was helpful in treating relapse after PCT.45 Abbreviated and Self-Help Formats A burgeoning area of interest has been the use of abbreviated or self-help treatments for anxiety disorders, and evidence is accumulating that such approaches are viable for panic disorder. For example, Craske et al.46 found a 4-session PCT protocol more effective than an equivalent amount of nondirective supportive therapy. Furthermore, Côté et al. found that 10 hours of in-person and telephone therapy was as effective as 20 hours of standard face-to-face cognitive-behavioral therapy administered over the same time period.47 The two groups combined (total N = 21) had a 90% panic-free rate at follow-up. However, the study is limited by the small number of subjects, which might have contributed to the lack of significant findings. Promising results also have been reported with selfhelp treatments involving minimal therapist contact (e.g., 3 hours).48–50 Hecker et al.,49 for example, found that self-directed PCT was not significantly different from therapist-directed PCT. The authors provided panic disorder patients (N = 16) with the first edition of the PCT workbook Mastery of Your Anxiety and Panic51 and randomly assigned participants to either a self-directed group or a therapist-directed group. Individuals in the therapist-directed group met with the therapist weekly J Psychother Pract Res, 8:1, Winter 1999 for 12 weeks to work through the materials. Participants in the self-directed group met with the therapist only three times over 12 weeks to assign readings and answer questions. Statistical tests revealed no difference between the two groups. Participants in both groups improved with treatment and maintained their gains at 6-month follow-up. However, the lack of significant findings might have been a result of the weak statistical power due to the small number of subjects. Unfortunately, the authors did not report the necessary information to calculate effect sizes. On the other hand, there is also some evidence to suggest that individuals having severe levels of interference and symptomatology may require more therapist involvement. For example, in a study of panic disorder patients with severe agoraphobia, therapist-administered treatment was substantially more effective than a selfhelp manual.52 Further enhancement of the cost-effectiveness and dissemination of PCT may be possible through the incorporation of new technologies into treatment. As early as 1987, Ghosh and Marks53 demonstrated that exposure therapy administered by means of a computer program was as effective as therapist-administered exposure for the treatment of agoraphobia. Recently, Newman et al.54 used a palmtop computer to administer a portion of the PCT. Preliminary data suggest that this method can lead to a significant reduction in the need for therapist contact. For a review of the current status of computer-aided treatments for mental health problems, see Marks et al.55 Overall, then, in cases that do not involve severe disability, there are effective alternatives to standard outpatient treatment by a therapist. Moreover, many empirically validated treatments have been published in manualized form, so that individuals can follow them either on their own or in conjunction with a therapist.10 Increased focus on services research will allow practitioners to determine the efficacy of this treatment format. USE OF PCT IN SPECIAL POPULATIONS Most studies of PCT have involved patients with a principal diagnosis of panic disorder (with limited agoraphobia) who were either unmedicated or on a stable dose of medication. However, researchers have begun to investigate its efficacy in other populations. Two examples are panic disorder patients being discontinued from benzodiazepine therapy and patients with schizophrenia and panic attacks. 7 Panic Control Treatment and Its Applications Patients Being Discontinued From Benzodiazepine Therapy The efficacy of benzodiazepine medications in the treatment of panic disorder has been well established,56,57 and two of these medicationsalprazolam and clonazepamare approved by the Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of panic disorder. Unfortunately, a drawback of these treatments is that a substantial proportion of patients relapse when drug discontinuation is attempted.58,59 Recently, several small studies have found that the administration of PCT concurrently with drug taper and discontinuation markedly improved the ability of panic disorder patients to stop and remain abstinent from benzodiazepine use. For example, Spiegel et al.60 assigned patients treated with alprazolam to either supportive medical management (SMM) with slow, flexible drug taper or the same taper procedure done concurrently with PCT. The taper procedure was highly effective in that 80% of subjects in the SMM group and 90% in the PCT group were able to stop alprazolam use for at least 2 weeks. However, by 6-month follow-up, half of the patients in the SMM group had relapsed, versus none in the PCT group. In a similar study, Otto et al.61 discontinued panic disorder patients from alprazolam or clonazepam either with or without concurrent PCT, using a somewhat faster, fixed taper procedure. Seventy-six percent of the patients who received PCT, versus 25% of those who did not, were able to discontinue drug use, and at 3-month follow-up, 77% of those in the PCT group who had discontinued the drug were still benzodiazepine free. We currently are participating in a larger, two-site study to confirm and extend those findings. PCT as a Treatment for Panic Attacks in Patients With Schizophrenia Patients with schizophrenia often report recurrent episodes of panic attacks.62,63 Most treatment studies of panic disorder and panic attacks in patients with schizophrenia have used benzodiazepines64 or imipramine65 as an adjunct to antipsychotic medication. In addition to the usual side effect and risk profile of benzodiazepines (sedation, cognitive impairment, and abuse potential), there is also some evidence of increased risk of behavioral and social disinhibition in schizophrenic patients taking some anti-anxiety medications. For panic attacks associated with schizophrenia, a 8 recent preliminary study suggests that PCT may be an effective alternative to pharmacotherapy.66 In that study, 11 consecutively admitted patients who met DSM-III-R criteria for schizophrenia and panic disorder participated in a 16-week open trial of group cognitive-behavioral therapy for panic disorder. Eight patients completed the treatment, with the majority of those showing significant reductions in both the frequency of panic attacks and functional interference due to panic attacks. Encouraged by those results, our group is currently conducting a controlled trial that is funded by the National Alliance for Research on Schizophrenia and Depression to evaluate the efficacy of PCT as a treatment to reduce panic attacks in patients with schizophrenia. Combination of PCT With Pharmacotherapy In their introduction to the report of the 1992 Consensus Development Conference on the Treatment of Panic Disorder, Wolfe and Maser67 noted that the modal clinical treatment for panic disorder at that time was a combination of medication and psychosocial therapy. More recently, Uhlenhuth68 reported that the consensus among world experts on pharmacotherapy for panic disorder still highly favors a combined treatment approach. These findings reflect the widely held belief that combined treatment regimens are superior to treatments administered alone, but there is very little empirical evidence to support that impression.69 Considering the added cost of combined therapy, it would seem important to demonstrate a sufficient benefit to warrant the expense. A recent review of published studies combining benzodiazepines and cognitive-behavioral therapy for panic disorder found little evidence that the combination was superior to cognitive-behavioral therapy alone for most patients.64 In fact, some studies have found poorer longterm outcomes for PCT when it has been administered in combination with benzodiazepines.25,60 Those findings are consistent with results from animal laboratories indicating that benzodiazepines may interfere with the types of learning that are most important for psychosocial treatment interventions.35,70 This potentially detrimental effect of benzodiazepines on the outcome of PCT appears to be minimized if the drugs are discontinued prior to the conclusion of PCT. Therefore, if benzodiazepines are to be prescribed in conjunction with PCT (e.g., when urgent relief of impairment due to panic symptoms is needed), it should be done as a temporary measure with J Psychother Pract Res, 8:1, Winter 1999 Hofmann and Spiegel the understanding that the medication will be tapered during the psychosocial treatment. The situation is less clear with regard to the combination of antidepressant medications and cognitive-behavioral therapy. Studies have fairly consistently found a benefit to combining an antidepressant with in vivo situational exposure therapy for patients with panic disorder and agoraphobia.26,71–73 However, there is little information regarding the combination of antidepressants with more cognitively focused therapies for patients with little or no agoraphobia. In the multicenter comparative treatment study of panic disorder referred to earlier,18 the combination of PCT plus imipramine was compared to PCT, imipramine, and a pill placebo, each administered alone, and to the combination of PCT and a pill placebo. Preliminary reports indicate that the combined treatment may be modestly better than either PCT or imipramine alone on some measures (although not overall response) during both acute and maintenance treatment but loses its advantage over PCT when the medication is discontinued.18 It would appear, on the basis of these data, that the routine administration of an antidepressant with PCT is not warranted; however, whether there are some patients for whom such an approach would be indicated is presently unknown. SUMMARY AND CONCLUSION Panic Control Treatment is a brief, structured, cognitivebehavioral therapy developed initially for the treatment of panic disorder with limited agoraphobia. The efficacy of PCT in its intended population has been well established, and when PCT is combined with a situational exposure module, its applicability may be extended to more agoraphobic patients. Follow-up assessments out to at least 2 years posttreatment show that patients as a group maintain their improvement, although individuals may experience some symptom fluctuation. The inclusion of a relapse prevention component may be helpful for those cases. In addition, there is some evidence that including a significant other in treatment may improve compliance with homework assignments and reduce interpersonal conflict associated with panic disorder. Among its more novel applications, PCT has shown promise in helping panic disorder patients to discontinue high-potency benzodiazepines and as an alternative to pharmacotherapy for treating panic attacks in patients with schizophrenia. Given the cost-effectiveness and clinical value of PCT and related therapies for panic disorder, it is imperative that efforts be made to make these treatments more widely accessible to patients. National probability samples indicate that only three out of four individuals with panic disorder seek treatment for their condition.74 Worse still, surveys consistently have shown that only a small number of those who do seek care receive empirically supported psychosocial treatments.5–7 As Barlow and Hofmann8 have noted, this latter situation is due at least in part to a lack of availability, especially in primary care settings, of therapists who have been trained in these interventions. A misguided belief that pharmacotherapy is less expensive than PCT may also be a factor. To facilitate its dissemination, PCT has been published in manual and workbook formats.10,11,75 In addition, there have been encouraging trials of self-help and computer-assisted versions, which may be useful when trained therapists are not available or to reduce the amount of therapist time required for treatment.46 Further efforts in this direction are needed and currently are under way. REFERENCES 1. Hofmann SG, Barlow DH: The costs of anxiety disorders: implications for psychosocial interventions, in Cost-Effectiveness of Psychotherapy, edited by Miller NE, Magruder KM. Oxford, England, Oxford University Press (in press) 2. Gould RA, Otto MW, Pollack MH: A meta-analysis of treatment outcome for panic disorder. Clin Psychol Rev 1995; 15:810–844 3. Otto MW, Pollack MH, Penava S, et al: The costs and benefits of cognitive-behavioral and pharmacologic treatments for panic disorder. Paper presented to the European Association for Behavioural and Cognitive Therapies, Venice, Italy, September 1997 4. American Psychiatric Association: Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with panic disorder. Am J Psychiatry 1998; 155(5, suppl) J Psychother Pract Res, 8:1, Winter 1999 5. Breier A, Charney DS, Heninger GR: Agoraphobia with panic attacks: development, diagnostic stability, and course of illness. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1986; 43:1029–1036 6. Taylor CB, King R, Margraf J, et al: Use of medication and in vivo exposure in volunteers for panic disorder research. Am J Psychiatry 1989; 146:1423–1426 7. Goisman RM, Rogers MP, Steketee GS, et al: Utilization of behavioral methods in a multicenter anxiety disorders study. J Clin Psychiatry 1993; 54:213–218 8. Barlow DH, Hofmann SG: Efficacy and dissemination of psychosocial treatment expertise, in Science and Practice of Cognitive Behaviour Therapy, edited by Clark DM, Fairburn CG. Oxford, England, Oxford University Press, 1997 9 Panic Control Treatment and Its Applications 9. Barlow DH, Craske MG, Cerny JA, et al: Behavioral treatment of panic disorder. Behavior Therapy 1989; 20:261–282 10. Barlow DH, Craske MG: Mastery of Your Anxiety and Panic II (MAP II). Albany, NY, Graywind, 1994 11. Craske MG, Barlow DH: Agoraphobia Supplement to the MAP II Program. Albany, NY, Graywind, 1994 12. American Psychological Association: Task Force on Promotion and Dissemination of Psychological Procedures: a report to the Division 12 Board of the American Psychological Association, 1993. Available from the Division 12 of the American Psychological Association, 750 First Street, NE, Washington, DC 20002-4242 13. Klosko JS, Barlow DH, Tassinari R, et al: A comparison of alprazolam and cognitive-behavior therapy in treatment of panic disorder. J Consult Clin Psychol 1990; 58:77–84 14. Klosko JS, Barlow DH, Tassinari R, et al: “A comparison of alprazolam and cognitive-behavior therapy in treatment of panic disorder”: correction. J Consult Clin Psychol 1995; 63:830 15. Craske MG, Brown TA, Barlow DH: Behavioral treatment of panic disorder: a two-year follow-up. Behavior Therapy 1991; 22:289– 304 16. Barlow DH: Long-term outcome for patients with panic disorder treated with cognitive-behavioral therapy. J Clin Psychol 1990; 51:17–23 17. Telch MJ, Lucas JA, Schmidt NB, et al: Combined pharmacological and behavioral treatment for agoraphobia. Behav Res Ther 1993; 23:325–335 18. Shear MK: Cognitive-behavioral therapy of panic disorder. Paper presented to the American Psychiatric Association, Toronto, Ontario, Canada, May 1998 19. Hofmann SG, Barlow DH, Papp LA, et al: Pretreatment attrition in a comparative treatment outcome study on panic disorder. Am J Psychiatry 1998; 155:43–47 20. Clark DM, Salkovskis PM, Hackman A, et al: A comparison of cognitive therapy, applied relaxation, and imipramine in the treatment of panic disorder. Br J Psychiatry 1994; 164:759–769 21. Margraf J, Barlow DH, Clark, DM, et al: Psychological treatment of panic: work in progress on outcome, active ingredients, and follow-up. Behav Res Ther 1993; 1:1–8 22. Clark DM, Salkovskis PM, Chalkley AJ: Respiratory control as a treatment for panic attacks. J Behav Ther Exp Psychiatry 1985;16:23–30 23. Hofmann SG, Bufka L, Barlow DH: Panic provocation procedures in the treatment of panic disorder: early perspectives and case studies. Behavior Therapy (in press) 24. Chambless DL, Gillis MM: A review of psychosocial treatments of panic disorder, in Treatment of Panic Disorder: A Consensus Development Conference, edited by Wolfe BE, Maser J. New York, Wiley, 1994, pp 149–173 25. Brown TA, Barlow DH: Long-term outcome of cognitive-behavioral treatment of panic disorder: clinical predictors and alternative strategies for assessment. J Consult Clin Psychol 1995; 63:754–765 26. deBeurs E, van Balkom AJLM, Lange A, et al: Treatment of panic disorder with agoraphobia: comparison of fluvoxamine, placebo, and psychological panic management combined with exposure and exposure in vivo alone. Am J Psychiatry 1995; 152:683–691 27. Emmelkamp PMG, Brilman E, Kuiper H, et al: The treatment of agoraphobia: a comparison of self-instructional training, rational emotive therapy, and exposure in vivo. Behav Modif 1986; 10:37– 53 28. Emmelkamp PMG, Mersch PP: Cognition and exposure in vivo in the treatment of agoraphobia: short-term and delayed effects. Cognitive Therapy Research 1982; 6:77–90 10 29. Michelson LK, Marchione KE, Greenwald M, et al: A comparative outcome and follow-up investigation of panic disorder with agoraphobia: the relative and combined efficacy of cognitive therapy, relaxation training, and therapist-assisted exposure. J Anxiety Disord 1996; 10:297–330 30. Öst LG, Hellstrom K, Westling BE: Applied relaxation, exposure in vivo, and cognitive methods in the treatment of agoraphobia. Paper presented at annual meeting of the Association for Advancement of Behavior Therapy, Washington, DC, November 1989 31. van den Hout M, Arntz A, Hoekstra R: Exposure reduced agoraphobia but not panic, and cognitive therapy reduced panic but not agoraphobia. Behav Res Ther 1994; 32:447–451 32. Williams SL, Rappaport A: Cognitive treatment in the natural environment for agoraphobics. Behavior Therapy 1983; 14:299–313 33. Vitali AE, Baker SL, Hofmann SG, et al: The efficacy of cognitive behavioral treatment followed by brief intensive exposure for panic disorder with agoraphobia. Poster presented at the annual meeting of the Association for Advancement of Behavior Therapy, New York, NY, November 1997 34. Milton F, Hafner J: The outcome of behavior therapy for agoraphobia in relation to marital adjustment. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1979; 36:807–811 35. Barlow DH: Anxiety and Its Disorders: The Nature and Treatment of Anxiety Disorder. New York, Guilford, 1988 36. Barlow DH, O’Brien GT, Last CG: Couples treatment of agoraphobia. Behavior Therapy 1984; 15:41–48 37. Cerny JA, Barlow DH, Craske M, et al: Couples treatment of agoraphobia: a two-year follow-up. Behav Res Ther 1987; 18:401–405 38. Arnow BA, Taylor CB, Agras WS, et al: Enhancing agoraphobia treatment outcome by changing couple communication patterns. Behav Res Ther 1985; 16:452–467 39. Craske MG, Burton T, Barlow DH: Relationships among measures of communication, marital satisfaction and exposure during couples treatment of agoraphobia. Behav Res Ther 1989; 27:131–140 40. Himadi WG, Cerny JA, Barlow DH, et al: The relationship of marital adjustment to agoraphobia treatment outcome. Behav Res Ther 1986; 24:107–115 41. Barlow DH, Seidner AL: Treatment of adolescent agoraphobics: effects on parent-adolescent relations. Behav Res Ther 1983; 21:519–527 42. Hiss H, Foa EB, Kozak MJ: Relapse prevention program for treatment of obsessive-compulsive disorder. J Consult Clin Psychol 1994; 62:801–808 43. Marlatt GA, Gordon JR: Relapse Prevention: Maintenance Strategies in Addictive Behavior Change. New York, Guilford, 1985 44. Öst LG: A maintenance program for behavioral treatment of anxiety disorders. Behav Res Ther 1989; 27:123–130 45. Hofmann SG, Barlow DH: Ambulatory psychophysiological monitoring: a potentially useful tool when treating panic relapse. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice 1996; 3:53–61 46. Craske MG, Maidenberg E, Bystritsky A: Brief cognitive-behavioral versus non-directive therapy for panic disorder. J Behav Ther Exp Psychiatry 1995; 26:113–120 47. Côté G, Gauthier JG, Laberge B, et al: Reduced therapist contact in the cognitive behavioral treatment of panic disorder. Behavior Therapy 1994; 25:123–145 48. Gould RA, Clum GA: Self-help plus minimal therapist contact in the treatment of panic disorder: a replication and extension. Behavior Therapy 1995; 26:533–546 49. Hecker JE, Losee MC, Fritzler BK, et al: Self-directed versus therapist-directed cognitive behavioral treatment for panic disorder. J Anxiety Disord 1996; 10:253–265 J Psychother Pract Res, 8:1, Winter 1999 Hofmann and Spiegel 50. Lidren DM, Watkins PL, Gould RA, et al: A comparison of bibliotherapy and group therapy in the treatment of panic disorder. J Consult Clin Psychol 1994; 62:865–869 51. Barlow DH, Craske MG: Mastery of Your Anxiety and Panic (MAP). Albany, NY, Graywind, 1989 52. Holden AE, O’Brian GT, Barlow DH, et al: Self-help manual for agoraphobia: a preliminary report on effectiveness. Behav Res Ther 1983; 14:545–556 53. Ghosh A, Marks IM: Self-treatment of agoraphobia by exposure. Behavior Therapy 1987; 18: 3–16 54. Newman MG, Kennardy J, Herman S, et al: Comparison of cognitive-behavioral treatment of panic disorder with computer assisted brief cognitive behavioral treatment. J Consult Clin Psychol 1997; 65:178–183 55. Marks IM, Shaw S, Parkin R: Computer-aided treatments of mental health problems. Clinical Psychology Science and Practice 1998; 5:151–170 56. Spiegel DA: Efficacy studies of alprazolam in panic disorder. Psychopharmacol Bull 1998; 34:191–195 57. Davidson JR, Moroz G: Pivotal studies of clonazepam in panic disorder. Psychopharmacol Bull 1998; 34:169–174 58. Fyer AJ, Liebowitz MR, Gorman JM, et al: Discontinuation of alprazolam in treatment in panic patients. Am J Psychiatry 1987; 144:303–308 59. Pecknold JC, Swinson RP, Kuch K, et al: Alprazolam in panic disorder and agoraphobia: results from a multicenter trial, III: discontinuation effects. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1988; 45:429–436 60. Spiegel DA, Bruce TJ, Gregg SF, et al: Does cognitive behavior therapy assist slow-taper alprazolam discontinuation in panic disorder? Am J Psychiatry 1994; 151:876–881 61. Otto MW, Gould RA, Pollack MH: Cognitive-behavioral treatment of panic disorder: considerations for the treatment of patients over the long term. Psychiatric Annals 1994; 24:307–315 62. Argyl N: Panic attacks in chronic schizophrenia. Br J Psychiatry 1990; 157:430–433. 63. Moorey H, Soni SD: Anxiety symptoms in stable chronic schizophrenics. Journal of Mental Health 1994; 3:257–262 64. Wolkowitz OM, Pickar D: Benzodiazepines in the treatment of schizophrenia: a review and reappraisal. Am J Psychiatry 1991; J Psychother Pract Res, 8:1, Winter 1999 148:714–726 65. Siris SG, Aaronson A, Sellew AP: Imipramine-responsive paniclike symptomatology in schizophrenia. Biol Psychiatry 1989; 25:485–488 66. Arlow PB, Moran ME, Bermanzohn PC, et al: Cognitive-behavioral treatment of panic attacks in chronic schizophrenia. J Psychother Pract Res 1997; 6:145–150 67. Wolfe BE, Maser JD (eds): Treatment of Panic Disorder: A Consensus Development Conference. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Press, 1994 68. Uhlenhuth EH: Treatment strategies in panic disorder: recommendations of an expert panel. Paper presented to the World Regional Congress of Biological Psychiatry, São Paulo, Brazil, April 1998 69. Spiegel DA, Bruce TJ: Benzodiazepines and exposure-based cognitive behavior therapies for panic disorder: conclusions from combined treatment trials. Am J Psychiatry 1997; 154:773–780 70. Wardle J: Behaviour therapy and benzodiazepines: allies or antagonists. Br J Psychiatry 1990; 156:163–168 71. Mavissakalian MG, Michelson L, Dealy RS: Pharmacological treatment of agoraphobia: imipramine versus imipramine with programmed practice. Br J Psychiatry 1983; 143:348–355 72. Zitrin CM, Klein DF, Woerner MG: Treatment of agoraphobia with group exposure in vivo and imipramine. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1980; 37:63–72 73. Telch MJ, Lucas RA: Combined pharmacological and psychological treatment of panic disorder: current status and future directions, in Treatment of Panic Disorder: A Consensus Development Conference, edited by Wolfe BE, Maser JD. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Press, 1994, pp 177–197 74. National Institutes of Health: Treatment of panic disorder. NIH Consensus Development Conference Consensus Statement, 9(2). Available from the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. National Institutes of Health, Public Health Service. Office of Medical Applications of Research. Federal Building, Room 618, Bethesda, MD 20892 75. Craske MG, Meadows E, Barlow DH: Therapist’s Guide for the “Mastery of Your Anxiety and Panic II” and “Agoraphobia Supplement.” Albany, NY, Graywind, 1994 11