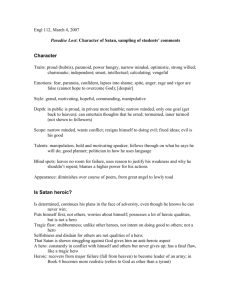

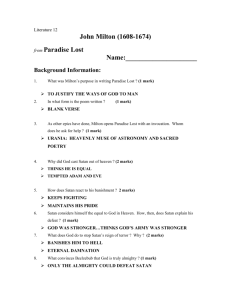

Paradise Lost

advertisement

Lindsey Jeanne Kennedy Epic Essay The extent to which the character of Satan in Milton’s Paradise Lost play the part of a Homeric Hero Satan is notoriously known for his deceptive, dark nature. When combined with the influence of Homer’s genius of ancient Greek epic identity, the product is Milton’s version of a controversial character. His first sanctioned disciple, John Milton is the first to initially seek and ultimately cultivate a sense of literary power through his epic work Paradise Lost. It is important to recognize that with Milton’s decision to establish an epic also comes his conscious decision to identify himself as an epic writer. Subsequently, this decision comes with assumed expectations, for himself and his readers, associated with not only the epic genre, but also preconceived prejudices concerning characterizations. That said, Milton’s figure of Satan inherently represents a controversial character surrounded by mixed reservation. Satan contrasts with classical Homeric heroes, yet upholds certain specific epic conventions. In Paradise Lost, Satan adheres to the classical epic hero, a character that can be compared with other classical hero’s such as Homer’s Achilles. A direct comparison can be made between Satan and Achilles in respect to their classical epic heroism, “He is a variant of Achilles, who equates honor with his own status . . . and feels slighted by his commander-in-chief, refuses his orders and believes himself superior” (Forsyth 30). Although Satan’s status is not that of a Greek warrior, he nonetheless possesses power. In addition, in Paradise Lost, God plays the role of Satan’s “commander-in-chief”, who rejects his acceptance and thus forces him upon evil. In respect to his function as a hero, “He is Odysseus and Jason on their heroic voyages, leader and chief warrior in battle during and after the War in Heaven, and through it all the most powerful speaker, able to rally and organize his troops with the eloquence of his appeals to their own heroic values” (Forsyth 30). Even though they are entirely dissimilar characters with unrelated roles, there are parallels that can be drawn between well-known Homeric heroes and Satan. While many of Satan’s roles in Paradise Lost do not justify his Homeric heroism, his earnest nature is one that accurately depicts him as such. With more courage and perseverance than the average mortal, Satan raises complex questions and concerns toward God. Although his inherent traits of deception and rebellion ring true in the end, in result of his eternal exile, his initial curiosity about and interest in the human life are legitimate. Even though he lacks the intelligence of Homeric heroes such as Odysseus, his naïve nature is not cowardly. On the other hand, Satan reflects a complex symbolic meaning that not only reveals Milton’s individual viewpoint but also counteracts the validity of his Homeric cognizance. Milton’s initial, positive portrayal of Satan in Book I as not only powerful, but also heroic is an unusual depiction of the notoriously dark character. This unfamiliar representation of such an infamously powerless creature creates an uncomfortable situation for the reader. Whichever interpretation is perceived, for the sake of this analysis, it is important to recognize and identify the range of traits in which Satan does possess, both characteristic of a Homeric hero and an entirely separate one. Perhaps the most prominent contradiction to Satan’s heroic qualities is that he does not fit the image of a hero in the traditional sense. This conflict allows one to consider that the traditional hero is in fact far more complex than one may perceive. For many readers of epics or any other genre, a hero is generally a male figure with good intentions who is faced with challenges. For instance, a classic Lindsey Jeanne Kennedy Epic Essay example of a Homeric Hero can be found in the young heart of Achilles, the Iliadic warrior leader. In almost every circumstance, heroes face specific challenges, which are successfully overcome time after time. Moreover, if these challenges are not overcome, like in the case of Achilles, they are persistently attempted until death defeats them. In Paradise Lost, Satan accomplishes his goal of corrupting humankind. Because this accomplishment is not admirable, however, it therefore creates an initial disturbance to a traditional expectation set for his heroic role. A traditional role of Homeric heroes is the practice of code of honor. Similar to Achilles’ commitment to battle comes his strong self-discipline and dedication to his word. Although Satan fails to consistently demonstrate honor throughout the entire poem, it is worth noting that his initial just-fallen angel exemplifies honorable qualities. From the beginning of Book I, Satan shows his determination to step up to God and face the challenges surrounding him. Although he is aggressive in nature, the ambition and courage that he demonstrates are similar to a Homeric hero: The Mother of Mankinde; what time his Pride Had cast him out from Heav’n, with all his Host Of Rebel Angels, by whose aid aspiring To set himself in Glory above his Peers, He trusted to have euald the most High, If he oppos’d; and with ambitious aim Against the Throne and Monarchy of God Rais’d impious Warr in eav’n and Battel proud With vain attempt (Milton I:36-44) Later in Book I, even after just awakening himself, he feels obligated to awaken the others, thus playing the role of a leader: “Aware, arise, or be for ever fall’n, / They heard, and were abasht, and up they sprung / Upon the wing” (Milton I:330-32). Along with honor comes the role of a leader, a traditional heroic trait widespread throughout epic poems, including the Iliad. Perhaps the best example of Satan’s leadership is in Book I after the angels have fallen: On the Beach Of that inflamed Sea, he stood and calld His Legions, Angel Forms, who lay instranst Thick as Autumnal Leaves that strow the Brooks In Vallombrosa” (Milton I:299-303) In addition, this is reiterated in following lines, “He calld so loud, that all the hollow deeps /Of Hell resounded” (Milton I:3I4-I5). His initial commencement and subjective role as a leader characterizes him as a hero in the very beginning of the epic. In order to then justify Satan’s heroism in this context, it is useful to consider Aristotle’s concept of hamartia. This concept allows one to understand the complexities associated with a realistic hero, as opposed to an ideal one (McManus). Satan has heroic thoughts, ideas and intentions, however his flaw is that he gets distracted by his own pride far too easily. His heroism therefore lies in his devout dedication in and determination to transform himself. Satan longs to change through the knowledge of not only his Lindsey Jeanne Kennedy Epic Essay true nature, but also God’s. “The process of moral self-determination – the driving urge toward selfdefinition that we normally recognize in the heroes of Homeric epic – is equally operative in Milton’s Satan, yet…this very preoccupation with self along with the craving for dominon and the hunger for glory, forms the cornerstone of the infernal city” (Steadman 254). His persistence is a heroic quality that drives him to challenge and question God. Although stereotypical intentions of Satan do shine through after his exile, he demonstrates the will to change for the better. Although Milton’s unique characterization of Satan does possess some qualities of a Homeric hero, he also retains many dishonorable traits as well. There is no doubt that Satan initially desires to return to Heaven. However, there is also no doubt that he has a tragic flaw in his pride and obsession of power and control. In other words, as much as Satan wanted to return to Heaven, he would not be satisfied there if he still remained to be below God. In that sense, his selfishness shines through, and shows the reader a different side of the otherwise heroic character. For example, in Book I Satan says: “Better to reign in Hell, then serve in Heav’n” (Milton I:263). This is a direct example of Satan’s all or nothing mentality, portraying the sinister side of his competitive nature. Nonetheless, he serves the function of a hero, but has a tragic flaw is much greater than that of which a Homeric hero can relate to. It is clear then to recognize Satan’s tragic flaw. After falling from Heaven, he threatens and challenges God for another chance. However, unsuccessful portrayal of weakness and vulnerability eventually yield his revenge: Farewel happy Fields Where Joy for ever dwells: Hail horrours, hail Infernal World, and thou profoundest Hell Receive thy new Possessor: One who brings A mind not to be chang’d by Place or Time. The mind is its own place, and in it self Can make a Heavn’n of Hell, a Hell of Heav’n (Milton I:249-55) Such oratory not only re-characterizes Satan but also debunks his heroic nature. It is appropriate then to conclude that although Satan does possess certain Homeric traits, overall he merely serves the function of a fundamental hero in Paradise Lost, with an entirely different purpose than Homeric heroes. It is obvious that although Satan has the same amount of power as Homeric heroes such as Achilles, he utilizes it in different ways. In Book I, we are shown that he channels his inability to redeem himself through alternative aggressive behavior: “Here at least / We shall be free / Here we may reign secure, and in my choice / To reign is worth ambition though in Hell” (Milton I:258-59; 26I-62). This change in Milton’s portrayal of Satan coincides with Satan’s inevitable acceptance of evil in Book IV: “So farewell Hope, and with Hope farewell Fear, / Farewell Remorse: all Good to me is lost; / Evil be thou my Good” (Milton IV:109-11). This infamous speech sanctions Satan’s inherent evil, and thus ends his final attempts at reaching Heaven. In conclusion, when judging Satan’s character, it is important to consider his entire role from Book I to Book V. Milton’s first impressions of him as a just-fallen angel represent powerful leadership and strong commitment. Whether Milton’s intention is for the reader to familiarize themselves with Satan Lindsey Jeanne Kennedy Epic Essay early on or not, his early character traits certainly make one consider the shared human traits between one and Satan. Throughout Paradise Lost, however, this Satan loses his grasp on reality. Ironically, his appearances change in accordance to his character as well. For example, when he is still mindful of Heaven and God, he is in a just-fallen angel. However, by Book V his demented view of Earth and Heaven coincide with his final appearance as a snake. This is worth noting because it is obviously not traditional for a Homeric hero to both physically and mentally transform throughout the time frame of the poem. Therefore, to the extent of his full character, with all considerations, Satan’s form does not represent that of a traditional Homeric hero. Lindsey Jeanne Kennedy Epic Essay Bibliographical References Forsyth, Neil. The Satanic Epic. Princeton, NJ: Princeton UP, 2003. McManus, Barbara F. Outline of Aristotle's Theory of Tragedy in the Poetics. Nov. 1999. Web. 23 Sept. 2010. <http://www2.cnr.edu/home/bmcmanus/poetics.html>. Milton, John. Selected Works. Paradise Lost. 1667. Steadman, John M. The Idea of Satan as the Hero of “Paradise Lost”. Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society, Vol. 120, No. 4, Symposium on John Milton. (Aug. 13, 1976), pp. 253-294.