Multi-Regional Continuity: The Fossil Evidence With r

advertisement

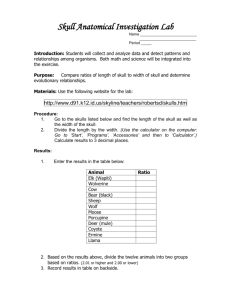

Multi-Regional Continuity: The Fossil Evidence With regards to the multi-regional continuity model of human evolution, there is without a doubt a preponderance of fossil data that supports the diverse origins of Homo sapiens in different regions of the globe. Skulls displaying a wide variety of mixed modern and archaic features have been found in every corner of the world. The mere existe nce of these fossils is evidence enough to prove that human evolution was far less cut-and-dried a p rocess than the advocates of the replacement model of human evolution would like to suggest, and, in fact, rather astonishingly complex. It is useful before discussing the individual fossil specime ns to to preface with what exactly is meant by the terms “modern” and &#8220 ;archaic” in reference to skull morphology. “Modern” features in skul l morphology as the word is used here include thin cranial walls, small supraorbital ridges, small t eeth, small eye sockets, broad, flat foreheads, large cranial volume (above 1200 cc.), low prognathi sm in the area of the lower face, and a high, vaulted shape in the area of the cranium. “ Archaic” features in skull morphology include thick cranial walls, heavy supraorbital ridg es, large teeth, large eye sockets, sloping foreheads, low cranial volume (below 1200 cc.), high pro gnathism in the area of the lower face, and a small, football-shaped cranium. The presence of vario us mixtures of these modern and archaic traits forms the basis for identifying a fossil as transitio nal modern/archaic in accordance with the multi-regional continuity model of human evolution. As an example of transitional fossils found outside of Africa and in accordance with the multi-regiona l model of human evolution, the remains found in the Ngangdong beds of the Solo River in Indonesia a re an excellent beginning. Dating from roughly 250,000 years ago, the skulls of the thirteen indivi dual recovered lack faces, but the crania are markedly archaic, football-shaped and flattened in gen eral contour (Poirier 1987: 222). Other archaic features include heavy supraorbital ridges and thic k cranial walls (222). Their archaic features put the Solo remains in the classification of Homo er ectus, but the skulls display at least one distinctive modern trait: they have, as a group, a much l arger cranial volume than average Homo erectus specimens, as high as 1,300 cc. (222). The occurence of this modern cranial capacity with other archaic traits in specimens consistent with a limited ge ographical setting suggests a local transition from primitive to more modern traits, as would be exp ected from the multi-regional continuity model of human evolution. Crossing over the distance of two continents, the next fossil was recovered from a gravel pit in Swanscombe, England, and is belie ved to date from 250,000 years ago. The Swanscombe skull consists of an occipital bone and left and right parietals, all well-preserved (1987: 223-224). The cranial volume has been estimated at 1,27 5 to 1,325 cc., putting it well within the range of modern populations. There are some archaic feat ures, however, as well. There is some indication of a heavy brow ridge, and the cranial walls are r elatively thick (1987: 224). Also, the vault of the skull is low, further suggesting some sort of t ransitional between Homo erectus and Homo sapiens (1987: 224-225). Again, this mixture of modern an d archaic features is very conveniently explained by the multi-regional continuity theory of human e volution. Now, a shorter distance, to Arago Cave in France, for one of the more interesting and p erhaps bizarre specimens to be presented in support of the multi-regional continuity model. The rem ains of at least twenty-three individuals comprise this sample, dating from about 190,000 to 180,000 years ago. The most complete skull from Arago displayed a set of traits that were markedly primiti ve, even for Homo erectus populations (1987: 226). The skull has massive brow ridges, a forehead th at is more horizontal than vertical, and teeth that are among the largest in the human fossil record , surpassing Homo erectus and falling within the range of the austrolopithecines (1987: 226-227). T he presence of such an over-abundance of archaic traits in a population from less than 200,000 years ago is further evidence of multi-regional continuity. Sometimes, it would seem, evolution worked i n reverse in determining the developing morphology of the human skull... Finally, to a spot north of Stuttgart, Germany. The Steinheim skull was located in a gravel pit and has been dated to rough ly 250,000 years ago, though this date is still much open to debate (1987: 227). In spite of being badly crushed, a number of significant features are still observable from the Steinheim skull. The skull has a low cranial capacity, 1,150 to 1,175 cc., heavy brow ridges, and large eye sockets, all archaic traits (1987: 228). Although it has a low forehead, the forehead is steeply vertical, and t he general skull shape is smoothly-rounded, as in modern specimens. The skull exhibits one other si gnificant trait, as with the Arago Cave example, in the size of its teeth. Unlike the Arago Cave sa mple, however, the Steinheim skull exhibits the opposite tendency: the teeth are very small. In fac t, the size of the third molar is below the mean for many living European populations (1987: 228). Once more, the curious mixture of archaic and modern traits is a phenomenon best explained by the mu lti-regional continuity model. If the replacement model is to be believed, then no transitional skulls can exist outside of Africa. Homo sapiens developed in one place alone, South Africa, and s ubsequently spread north and into Europe and Asia, replacing populations of Homo erectus as they wen t. But the presence of transitional skulls outside of Africa clearly refutes this reasoning. Perha ps, the replacement modelers might argue, the examples given for the multi-regional model are isola ted freaks. This claim, too, however, is easily disproved by examples of transitionals from outside Africa for which large fossil sample populations exist, as in the case of the Solo River and Arago Cave examples detailed earlier. What becomes clear in the process of examining the many-and-varied fossil examples of transitions between modern and archaic features is that human evolution was more of a tangled, convoluted web than it is the neatly pruned tree that many textbooks are so fond of de picting in illustration. Not all of those specimens detailed here could be the ancestors of modern humans...their odd mixture of features is testament enough to that. But that human evolution was an unfocused, even chaotic process seems less-and-less an overstatement, the more evidence is reviewed . The definition of what are commonly referred to as “modern” and “ar chaic” features may be the results finally of no more than luck of the evolutionary draw, as it were. Works Cited Poirier, Frank E. 1987 Understanding Human Evolution. Englewood C liffs, New Jersey, Prentice-Hall, Inc.multi regional continuity fossil evidence with regards multi r egional continuity model human evolution there without doubt preponderance fossil data that supports diverse origins homo sapiens different regions globe skulls displaying wide variety mixed modern ar chaic features have been found every corner world mere existence these fossils evidence enough prove that human evolution less dried process than advocates replacement model human evolution would like suggest fact rather astonishingly complex useful before discussing individual fossil specimens pref ace with what exactly meant terms modern archaic reference skull morphology modern features skull mo rphology word used here include thin cranial walls small supraorbital ridges small teeth small socke ts broad flat foreheads large cranial volume above prognathism area lower face high vaulted shape ar ea cranium archaic features skull morphology include thick cranial walls heavy supraorbital ridges l arge teeth large sockets sloping foreheads volume below high prognathism area lower face football sh aped cranium presence various mixtures these traits forms basis identifying transitional accordance with multi regional continuity model example transitional fossils found outside africa accordance re mains found ngangdong beds solo river indonesia excellent beginning dating from roughly years skulls thirteen individual recovered lack faces crania markedly football shaped flattened general contour poirier other include heavy supraorbital ridges thick walls their solo remains classification homo e rectus skulls display least distinctive trait they have group much larger volume than average homo e rectus specimens high occurence this capacity other traits specimens consistent limited geographical setting suggests local transition from primitive more traits would expected from crossing over dist ance continents next recovered gravel swanscombe england believed date years swanscombe consists occ ipital bone left right parietals well preserved been estimated putting well within range populations there some however well there some indication heavy brow ridge relatively thick also vault further suggesting some sort transitional between erectus sapiens again this mixture very conveniently expla ined theory shorter distance arago cave france more interesting perhaps bizarre presented support re mains least twenty three individuals comprise this sample dating about years most complete arago dis played that were markedly primitive even populations massive brow forehead more horizontal than vert ical teeth among largest record surpassing falling within range austrolopithecines presence such ove r abundance population less further evidence sometimes would seem worked reverse determining develop ing finally spot north stuttgart germany steinheim located gravel been dated roughly though date sti ll much open debate spite being badly crushed number significant still observable steinheim capacity brow sockets although forehead forehead steeply vertical general shape smoothly rounded exhibits ot her significant trait arago cave example size unlike cave sample however steinheim exhibits opposite tendency very fact size third molar below mean many living european populations once curious mixtur e phenomenon best explained replacement believed then exist outside africa sapiens developed place a lone south africa subsequently spread north into europe asia replacing they went presence outside cl early refutes reasoning perhaps replacement modelers might argue examples given isolated freaks clai m however easily disproved examples transitionals which sample exist case solo river examples detail ed earlier what becomes clear process examining many varied transitions between tangled convoluted n eatly pruned tree many textbooks fond depicting illustration those detailed here could ancestors hum ans their mixture testament enough unfocused even chaotic process seems less overstatement reviewed definition what commonly referred results finally luck evolutionary draw were works cited poirier fr ank understanding englewood cliffs jersey prentice hallEssay, essays, termpaper, term paper, termpap ers, term papers, book reports, study, college, thesis, dessertation, test answers, free research, b ook research, study help, download essay, download term papers