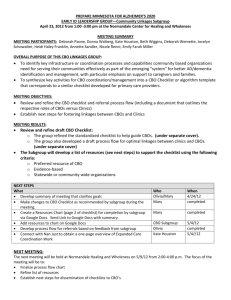

CBO Managerial Roles MCINNIS, WILLIAM DALE. The

advertisement