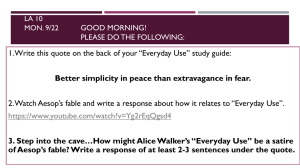

The Everyday Use of Quilts

advertisement

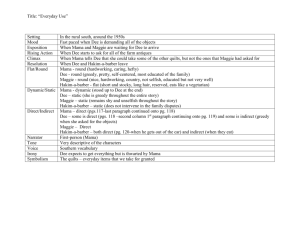

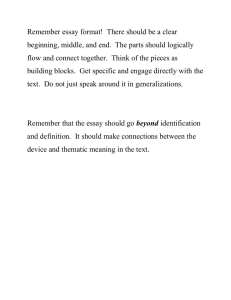

Dix 1 Rebecca Dix Dr. Mosser Paper 1 September 26, 2012 Every Day Use of Quilts: Opposing Views on Preserving Heritage Alice Walker’s “Everyday Use” tells the story of an African American family with differing individual perspectives on the meaning behind their cultural heritage. Walker uses a first person narrative, told from Mama’s perspective, to highlight the differences between her two daughters, Dee and Maggie. On the one hand, Dee is the progressive eldest daughter, otherwise known as Wangeroo Leewanika Kemanjo, who attempts to take ownership of the family’s handmade quilts during a visit home. On the other hand, Maggie is the more traditional, younger sibling, who does not go to college, but remains significantly in touch with the family history behind the quilts. Throughout the story, conflict arises surrounding both daughters’ unique perspective on how the quilts should be put to use. In the end, Mama, who, like Maggie is not college educated, assumes authority over the situation, and gives both quilts to Maggie. In the story, Walker uses quilts to symbolize a communication barrier between traditional and progressive viewpoints on preserving the family’s cultural heritage. Walker’s character, Maggie, represents the traditional perspective on heritage. Early on, Maggie is depicted as a quiet and helpful daughter, at peace with the poverty she is seemingly destined for (407). During the conflict, Mama narrates, “It was Grandma and Big Dee who taught her [Maggie] how to quilt herself,” which suggests Maggie’s understanding of the effort behind each quilt’s construction as well as the connection she holds with Dix 2 family members who define portions of her cultural heritage (411). When Dee argues with Mama about the quilts, she reasons, “Maggie would put them on the bed and in five years they’d be in rags” (411). In this way, Dee’s statement suggests that Maggie’s idea of “everyday use” will destroy the quilts, which are a source of heritage that should be preserved and untouched. In context, Maggie’s decision to use the quilts as household items make sense because she will need the quilts to keep warm at night and does not have enough money to waste on new quilts. From the traditional perspective, Maggie and Mama see quilt construction to be synonymous with heritage construction, a participatory process that acts as a familial foundation, a way to preserve the past. Since Maggie’s grandmother and aunt taught her to stitch, she has participated in the construction of their heritage, and deserves the quilts because she is part of that aspect of the family’s heritage. In addition, this perspective suggests that heritage should be preserved as a continuation of the past, and should be used to grant necessities, in this case a warm bed, to future family members in need. However, Dee, the progressive sibling, does not see the quilts in the same way. Dee’s character reflects attributes of Walker’s time at Spellman College and Sara Lawrence University, where Walker participated as an activist for the Civil Right’s Movement. Furthermore, Spellman College was an “all‐black” education system, and when Walker received a scholarship to attend Sarah Lawrence in New York, “She felt that she had more intellectual freedom,” a progressive attitude similar to Dee’s worldview on the progressive importance of education (“Where Life and Art Intersect” 3‐4). Although Dee was named after her aunt Dicie, Big Dee, and Grandma Dee, when Mama asks about her name change, she appears to reject her familial heritage by stating, “I couldn’t bare it any longer, being Dix 3 named after the people who oppress me” (408). Dee’s response suggests a need to remove her life from the oppressive past and progress forward into the future. In this way, Dee is ready to renounce her connections to slavery, a stigma, which in her opinion labels African Americans as inferior to whites. In addition, Dee’s version of “everyday use” involves hanging the quilts as relics of the past, an aesthetically appealing source of intellectual conversation for enlightened thinkers. Similarly, Dee wishes to decorate her house with the family’s churn top and dasher, whittled by Uncle Buddy and Aunt Dee’s first husband Henry (409‐10). After reluctantly allowing Dee to have the churn top and dasher, Mama is confused by Dee’s insistence to take the quilts: “I didn’t want to bring up how I had offered Dee (Wangeroo) a quilt when she went away to college. Then she had told me they were old‐fashioned, out of style” (410‐11). Mama’s comment is important because it shows that college aided in the evolution of Dee’s thought processes. Perhaps, education has given Dee the ability to think critically about preserving her heritage, causing her to focus on the quilt’s aesthetic qualities. To Dee, the quilts should be remembered and admired as artistic heirlooms. In this way, Dee perceives the churn, quilts, and dasher as the perfect means to represent her roots to others, just as changing her name to Wangeroo and wearing vibrant flowing dresses and chunky bracelets illustrates a connection with her African roots (408). Furthermore, Dee’s perspective on heritage unveils a desire to present the quilts as the artistic legacy of her family’s heritage, which, in preserving the items as art, presents an innovative way to eliminate the “old‐fashioned” thought processes that she believes hinders Maggie and Mama’s path to prosperity. Dix 4 All in all, Walker uses the quilts to symbolize a communication barrier between traditional and progressive family members by presenting two differing perspectives on heritage preservation, which, in many ways, both viewpoints are equally justifiable. Walker uses Mama to describe the quilts, narrating: In both of them were scraps of dresses Grandma Dee had worn fifty and more years ago. Bits and pieces of Grandpa Jarrell’s paisley shirts. And one teeny faded blue piece, about the size of a penny matchbox, that was from Great Grandpa Ezra’s uniform that he wore in the Civil War. (410) In this way, Walker uses descriptive language, pertaining to the family’s past, to define how the construction of a quilt is necessary for future generations to conceptualize meaning behind each mismatched piece of fabric. On the one hand, Maggie’s character understands that preserving heritage is preserving the unseen efforts put forth in the creation of one’s heritage. Maggie represents the quilt’s intricate stitching and fluffy cotton insides, used to keep the quilt together and give warmth to those who need comfort. On the other hand, Dee’s character communicates the principle of preserving heritage as a natural progression of human thought and beauty. Dee wishes to preserve the significance behind the quilt’s artistic design, which is why she does not want the quilts to go to ruin. For instance, the “teeny faded blue piece” may fall off, eliminating Grandpa Ezra and his life as a Civil War soldier from the family’s heritage and collective conscious. Thus, the quilts symbolize a communication barrier because, although both Dee and Maggie desire ownership, neither side can understand what it means to be parts of a whole. Although Maggie offers the quilts to Dee, she still wants them for herself because she makes the comment “like somebody used to never winning anything, or having anything reserved Dix 5 for her” (411). In this way, Maggie’s traditional ways cause her to submit, which furthers the communication barrier because, during Civil Rights, traditional views caused many African Americans to submit to others, not stand up for themselves. In the end, if members from the family’s past had never made the quilts, then Dee would not consider the quilts to be representative relics of her family’s heritage. In contrast, if Grandma Dee and Aunt Dicie had not taught Maggie how to quilt, then she would not have such a personal connection with the family’s history. All in all, Maggie appreciates the craft behind the values, and Dee wishes to converse and compound on the values and aesthetics produced by the craft with intellectual comrades. Furthermore, Walker creates Maggie and Dee as unique characters, and their conflicting perspectives work together, as parts of a whole within the story. Overall, “Everyday Use” illustrates that preserving heritage requires two kinds of people. First, there are people like Maggie, a lover of the craft, who knows that each stitch further binds her family together and grants peace, even to those who do not possess superior mindsets. Second, there are people like Dee, projector of the values within the craft, who refuses complacency and dedicates her life to learning, communicating, and understanding artistic value and cultural roots. Furthermore, the communication barrier within Walker’s story, symbolized by quilts, is necessary because it allows readers to see the ways that heritage acts to preserve the family’s past as well as progress higher understandings of human values and purpose into the future. Dix 6 Works Cited "Where Life and Art Intersect." National Council of Teachers of English. N.p., n.d. Web. 24 Sept. 2012. <https://secure.ncte.org/library/NCTEFiles/Resources/Books/Sample/01143chap01.pdf>.