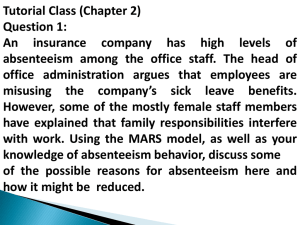

work related attitudes as predictors of employee absenteeism

advertisement