CBA Guide V3 Final March 2009 - National Defense Industrial

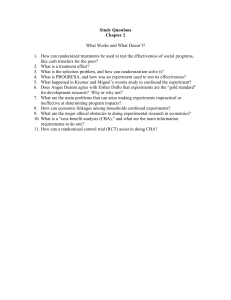

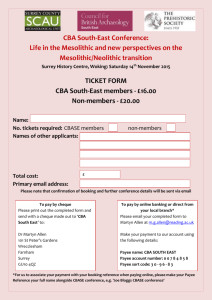

advertisement