Video Streaming: the current state of play in an

advertisement

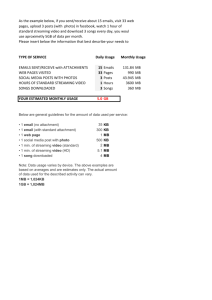

Video Streaming: the current state of play in an academic setting Diana Blackwood, Curtin University of Technology, Western Australia Introduction Curtin University of Technology is Western Australia’s largest university with over 40,000 students studying at Curtin in 2008. Curtin has several campuses both in regional WA and offshore (Malaysia, Singapore) and around 10,000 students are studying at these campuses or by distance education. The University is committed to providing a student-centered learning environment and encourages teaching areas to provide flexible learning opportunities that will meet the needs of a diverse student population. Flexible learning incorporates access to learning resources via contemporary technologies for example, e-Reserve, internet technologies and the use of learning management systems; the flexible delivery of learning experiences and assessment, for example iLectures, podcasting; and distance education. The University has developed an extensive infrastructure to support flexible learning. Curtin IT Services supports staff in training and use of both learning management systems such as Blackboard and iLectures. The Curtin iLectures unit currently records and uploads over 6,000 lectures, seminars, conference sessions, video and audio reference material each year. This represents approximately 300 – 400 hours of video and audio each week - an extensive “streaming service” and infrastructure in which the Library was able to participate. From 2006 onwards, academics at Curtin started to make requests for streamed video content. This was generally from pre-purchased videos and DVD’s in the Library’s audiovisual collection that they had previously used to support their teaching. They wanted to make this content more widely available in an online environment. This paper will examine why Curtin University academics started to request streamed video content; it will provide an overview of the licensing, copyright issues and storage issues associated with making digital video content available in a University setting; and will investigate the growing number of potentially useful sources of digital video available in Australia and overseas. I will discuss these in both their local and international contexts. What is video streaming? In simplest terms video streaming is the showing of video over the internet. More technically, streaming media uses a streaming server to transmit audio, video and multimedia via digital code as a continuous real-time stream. Using an appropriate player to view the stream, users do not have to download large files on their computers. As soon as enough data has been received and stored in the buffer, the video will start to play. The buffer is continuously refreshed as the streamed content is viewed and no files are left behind. 1 Streaming media has become part of our everyday experience of the internet. Digital video abounds on a multitude of websites such as television news broadcasts and programs, sporting events, news sites and concert webcasts. The medium can be delivered in real time or on demand and is used to promote, advertise, entertain and educate. Many universities are including video clips on their websites in order to provide more interactive and visual content for prospective students. See the welcome to country on Curtin University’s website for example. In what way do academics want to use streamed video content and what do they perceive the benefits to be for their students? The Curtin experience At Curtin University, requests to stream video content came largely from the Faculty of Health Sciences, notably from the Schools of Physiotherapy, Occupational Therapy & Social Work and Psychology. There has been one request from Curtin Business School and one from the Faculty of Humanities. 1. Peter Allen from the School of Psychology uses streamed video from a variety of sources, including the streaming of pre-purchased DVD content where the streaming rights have been investigated and arranged by the Library. However, he also directs students to video content on the internet (eg. Google Video, the Internet Archive, TED, ABC and so on). Allen shows this content in lectures embedded in PowerPoint and sometimes embeds in Blackboard. He is keen for the Library’s E-Reserve to accept mediums other than text, such as the streaming content he is using and demonstrating. Allen has commented “I tend to think that students develop a much deeper understanding of concepts when they are illustrated by examples”. When using examples such as the bystander apathy study by Darley & Latane in the Kitty Genovese murder, he states “I could …bullet point my way through… (which seems like a bit of a wasted opportunity considering the technologies and multimedia content now available to us) or present them with a mixture of video graphics etc.” In terms of supporting student outcomes, Allen is keen to point out that digital video should illustrate and not obscure meaning and that lectures ensure that students can draw links from the streamed content to the theoretical material that it is supposed to be illustrating. (P. Allen, personal communication, Nov 12, 2008). 2. Stephanie Parkinson from the School of Physiotherapy, is keen to use streaming content to assist students who are effectively off campus due to full time clinical placement. In two instances Parkinson has asked the Library to investigate a streaming video licence – once for an assessment DVD of the Chedoke McMaster Stroke Inventory and one for a German DVD on using stroke affected limbs. In one instance Parkinson streamed an in house video produced by her School. Like Peter Allen from Psychology she is keen for the streamed content to be placed in the Library’s E-Reserve for her relevant units. Parkinson states that third, fourth and Graduate Entry Masters students in full time clinics have limited time to study and limited time on campus. The benefits of making the DVD’s available by streaming are that students are not at the mercy of the DVD being available for loan, and that students can watch them whilst on clinical placement. In Parkinson’s opinion both videos help students with 2 observational skills as well as potentially increasing their accuracy in assessment skills with real patients in clinics. Students themselves have informally requested to have in house video content available to them as it helps them have a better clinical picture of what movement abnormalities look like if they are exposed to them more often. (S. Parkinson, personal communication, Nov 14, 2008). 3. Fran Crawford from the School of Social Work requested a video to be streamed for which we were unable to obtain clearance for digital rights. Crawford consequently streamed in house videos specially made by a Curtin University research unit for a Social Work conference in Perth. Crawford agrees with Parkinson that the availability of streamed content is much easier than taking the video out of the library. She states “The videos were originally made to translate abstract concepts of qualitative research into everyday social work contexts and over the time that I have used them, they have served this purpose well. Streaming allowed me to use them without taking up lecture time”. (F. Crawford, personal communication, Nov 16, 2008). Australian Universities Both the University of Melbourne and the Royal Melbourne Institute of Technology (RMIT) Library have made pages of streamed video links from Australian TV stations available on their websites. They have used a simple browsable interface. No information on the success of these projects was available at the time of writing this paper. UK and US academic and digital libraries The literature presents a vast array of uses of streaming video in academic libraries. Streaming video can be used to replicate a lecture, demonstrate a process or a practice and played to all learners at the same time (synchronously) or viewed asynchronously or on demand. Shephard (2003) cites a number of interesting case studies from the UK higher education sector. These include using a streamed video for Nursing students in a group lecture situation to provide a ‘real patient scenario; using a live stream during a practical class to teach ‘how to measure blood pressure’; use of a video stream to describe a technical procedure in a cooking demonstration; and the use of an instructional steaming video for medical students on how to examine patients. Shephard also discusses the variety of websites that exist which encourage academic staff to engage with this technology and experiment with it. Boeke (2004) has surveyed a number of worldwide digital libraries which include UK and US universities and has discussed how “streaming technology provides great potential for digital libraries to increase access to their specialized video and audio collections over the internet.” (p. 1) Participants have cited the usefulness of the media when applied to oral histories, video collections, off-air TV News archives and the digitisation of rare and unique sound recordings for the Hoagy Carmichael Collection at Indiana University. Other studies discuss the use of streaming video in telemedicine and dentistry (Engilman, Cox, Bednar, & Proffit, 2007; Hahm et al., 2007), engineering (Ranaldo, Rapuano, Riccio, & Zoino, 2007) and for catering and fashion marketing students. (Strom, 2002, May) The application of streaming video for off campus and distance 3 education students has been discussed by Mullins-Dove (2006) who also mentions the use of streaming video in the recruitment of new students. In terms of perceived benefits, the literature presents conflicting viewpoints. Ross (2005) states “the use of video streaming in education is exciting and multifaceted. Research has shown that the use of video content leads to more attentive, more knowledgeable and higher achieving students” whereas Shephard (2003, p. 295) states that in regard to streamed video there is “relatively little evidence-base in the educational literature to support its use or development”. Shepherd’s concern is that the case studies she cites represent what she calls ‘action research’ which demonstrate very little formal evaluation and states ”to what extent did the students learn from the video or from any number of additional resources” (p. 297). She does however, acknowledge the enthusiasm with which academics entered into the projects she discusses and the collaborative teamwork that each required. Mullins-Dove (2006, p.67) however, states that “Recent Studies indicate that whether or not the use of streaming video actually increases student achievement, perceptions of this technology are positive, both by instructors and students.” Licensing and copyright issues Licensing In October 2007, Curtin Library emailed a number of our main video suppliers to establish a picture of licensing issues related to digital streaming. Our specific queries were: • as a publisher are you prepared to grant us a license to stream content if we already hold one of your videos or DVDs? • if so, what would be the likely conditions of the license? • are you able to indicate the likely cost of negotiating a license to stream video content? The responses varied enormously: • Some give permission with no extra charge for the library to pay; • Some require a license fee to be paid for each title to be streamed. This could be modest annual fee others or a fee calculated on the number of students, the number of campuses, the length and age of the tile to be streamed etc; • Some do not give permission to digitize’ or otherwise reproduce into a digital format or copy on to a server, any DVD, VHS or digital titles or materials; • Some do not have a policy, guidelines or costing for streaming items distributed by their company; • Some will agree to stream with the proviso that the content is to be used for a particular course and group of students in a password protected environment. Course content is to be distributed through recognized course management software, such as Blackboard or WebCT. Some producers do charge a fee for each semester the content is used, thus, the content must be disabled and a new fee paid each time the course is offered. • Some stipulated one campus only NOTE: Not all suppliers are producers and very often they work as an intermediary between a producer and a library. 4 In the Library’s investigations into streaming permissions, the issue of license fees has not yet come up. All requests from academics have either been for titles which did not charge or for Australian TV programs that we were able to obtain from authorised suppliers for a modest fee (see below). There is an expectation from Faculty that the Library would pay any licensing fees and administer license agreements in they way that is currently done for electronic journals and databases. If costs are simply too high, the Library could exercise it’s discretion in refusing to obtain an expensive title. If Faculty still wanted to proceed, it would then be a matter of them negotiating and paying themselves. For example, one supplier quoted the following when asked about costs. If Curtin University of Technology (40,000 students) wanted a digital streaming licence for one title for one year it would cost $965, for two years it would cost $1447.50, and three years $1930. For ten titles it would cost $2450 for one year, $3675 for two years and $6125 for three years! Our US colleagues have more experience in the development of online video collections. Even so, the consensus appears to be that “at the moment it seems to be a particularly intricate process to secure video streaming content.” Prosser (2006, p. 5). Alberico (2007, p.1) states that “large scale licensing and online distribution of commercial educational video by libraries or library consortia is a relatively new phenomenon.” He suggest that it is 10 years behind licensing models for e-journals and databases and goes on to say “It remains to be determined whether the online educational video market will move to pay per view approach, a vendor hosted subscription model or a rights purchase arrangement with the licensee assuming responsibility for hosting the streams.” (p.4) Clark (2005) states that ”digital licensing is a relatively new field for video: some licensors are established, others are working out agreements on a case by case basis.” Copyright What we can’t do On the subject of copying videos or DVD’s by educational institutions for the purpose of video streaming, Australian copyright law as stated in the Australian Copyright Council’s information sheet Videos & DVDs: copying & downloading (Australian Copyright Council, December, 2006), says: “There are no specific exceptions that allow educational institutions to copy purchased, rented or borrowed videos or DVDs for educational purposes….. ……. an educational institution may be able to make a copy of a video or DVD for educational instruction provided: • the circumstances of the use amount to a special case; • the use does not conflict with a normal exploitation of the contents of the video or DVD; • the use does not unreasonably prejudice the legitimate interests of the owner of the copyright; and • the copying is not made for commercial advantage or profit.” It is doubtful that the Library could use any of these exceptions in order to copy videos or DVD’s for streaming. On the Australian Copyright Council’s website under Recent Q&As on copyright for education and teaching, the following is stated with regards to the question Can a teacher video-stream a commercially produced DVD to a class? 5 “This depends on the type of technology being used to facilitate the streaming. The Copyright Act allows you to play a commercially produced DVD in class where the instruction is not for profit, and to ‘communicate’ it electronically (for example, by streaming). However, unless the DVD is a “Screenrights copy” [see below] (that is, a copy of something broadcast on TV), in most cases the Copyright Act would not allow you to copy it onto the server or content management system you are using in order to stream it. In most cases, copying a commercially-produced DVD would involve circumventing an access-control technological protection measure (such as CSS), and this is prohibited by the Copyright Act. If the DVD is not protected by an access-control technological protection measure, you may be able to copy it in order to stream it for a class under the “special case” exception for educational institutions. You are more likely to be able to rely on this exception to copy the DVD if: • you need to show the DVD for a specific class; • it is not feasible to stream the DVD without copying it; • you cannot get an off-air copy made under the scheme administered by Screenrights; • you don’t make more copies than are needed in order to show to the particular class; • students are not able to download the film; and • you do not keep the copy for any longer than you need it for the class.” What we can do- AVCC Part VA license The University’s Part VA licence is one of the statutory licensing schemes in which Curtin University participates through the Australian Vice-Chancellors’ Committee. For payment of a fee to the relevant copyright collection society (“Screenrights”), the University is permitted under particular conditions, to copy and communicate broadcasts (television, radio, cable and satellite) for educational purposes. For example, an academic could tape an episode of the ABC’s 7:30 Report and then have this tape uploaded to a university streaming server and make it available to students. If the academic misses the program and wants to make it available, another option is to purchase it from two Australian companies Tape Services and Enhance TV. These two organisations are authorised to tape TV programs off-air and make them available to educational institutions for a small charge and hold large collections of TV programs copied previously. The Library used their services for an SBS program which was requested to be streamed by an academic in the School of Public Health. Other sources of streamed video content Vendor hosted content Curtin University Library has taken out a subscription to Informit Media’s relatively new product TV News. This will be available for clients from January 2009 at a cost to the Library of A$30,000. This database provides access to Australian Television News and current affairs programs as well as TV documentaries. The 2008 trial to this database was a huge success with academics. Informit, the commercial arm of RMIT has used the Screenrights agreement mentioned earlier to be able to copy these TV programs. 6 Programs can be viewed from the site as progressive downloads (progressive downloads represent a HTTP download from a Web site rather than streaming downloads from a streaming server). If academics want to place the programs in an online learning management system, the files are available as video downloads rather than streams. This has raised concerns regarding the cost of the downloads and the implication this will have for students’ monthly internet usage quotas. Another vendor who will shortly be releasing streamed video content is Alexander Street Press. Two of their products are Theatre in Video and Counseling and Therapy in Video. These not only provide online video content, but also provide the type of functionality that you would expect on a database platform such as indexing and searching, the ability to bookmark, annotate, cite, link to, put into playlists or folders, and share—with permanent URLs. It also allows users to create video clips and embed them wherever they like. The latest quote for Counseling and Therapy in video was US$20,000. Consortial models using one supplier of video content Two University consortia who have set up video projects are OhioLINK and VIVA (Virtual Library of Virginia). The Digital Media Center at OhioLINK, a consortium of 89 college and academic libraries in Ohio, is providing access to a variety of multimedia material including educational films and documentaries. OhioLINK uses Films On Demand , a web-based digital video delivery service that allows clients to view streaming videos from Films Media Group FMG. They have over a thousand titles in their collection and use a common authentication system. VIVA, a publicly supported consortium of libraries at 71 higher education institutions, has licensed the rights in perpetuity to around 500 titles from the US Public Broadcasting Service (PBS). These titles are made available by video stream to consortium members using a Shibboleth-enabled streaming service hosted at the University of Virginia. PBS requires authentication by username and password. James Madison University, as a member of VIVA has access to the PBS material but have also incorporated other streaming video suppliers into their collection – see http://www.lib.jmu.edu/resources/video.aspx. JMU has purchased content form big suppliers such as Discovery Education Streaming but also free content from ResearchChannel and Annenberg Media. Pay per view One supplier SourceLearn which is collaborating with BBC Active, has developed a pay per view model. SourceLearn is available only to academic staff at European institiutions. Their website states “With SourceLearn you pay only for programs that your students use. You choose which programs your students can watch and when they can watch. You will be billed only when your students actually view the programs and you will pay only for what has been viewed. Cost are exceedingly low making SourceLearn the most economical way to license media for learning”. Where to store streamed content? Curtin Library The question that Curtin Library is currently investigating is where to place streamed video content. At present content is being stored on one of Curtin’s streaming servers and being made available by academics in their Blackboard units. 7 However, in relation to broadcasts that have been taped off-air and streamed as part of the Part VA Licence mentioned earlier, the University’s copyright policy and procedures document, Nov 2005 states that: “Online (web) communication … broadcasts must be arranged via the Library’s webbased Electronic Reserve system”. If this is a requirement for broadcasts streams, it would seem logical for Curtin University to place all video streamed content in E-Reserve. Two Curtin academics, Peter Allen and Stephanie Parkinson have indicated that this would be their preferred option. The main stumbling block to this approach is that some suppliers are asking that their streamed content by only made available to students within a particular course within a course learning management system. Although E-Reserve partially complies with this as students are required to log in to see scanned journal articles and book chapter, E-Reserve is a subset of the total library catalogue and as such can be accessed by all students. This may be an area where negotiation needs to take place with suppliers. There is also the question of which organization unit within the Library itself will manage the streamed content. All indicators would point to the need for a collaborative approach. Requests for streaming content are generally received by Faculty librarians, the Resources & Access staff (acquisitions, technical services & IT) make enquiries about licensing, the streaming itself is carried out by the Curtin iLectures unit which is part of Curtin IT Services, then if content is going to be held in E-Reserve, it would be managed by the E-Reserve staff. At the time of writing this paper, this issue was under discussion with all Library stakeholders. What are other universities doing? A number of interesting projects are reported in the literature which have addressed the issue of where to store content. The first is James Madison University where records to streamed video are placed in the catalogue. DVD’s are purchased, streamed and uploaded to the streaming server by IT staff and then catalogued. (Clark et al., 2005) Online videos can be searched by title or keyword in the catalogue, at a collection level by clicking on the series title in the catalogue record or by accessing the collection at the database level by accessing the Madison Digital Image Database (MDID) at http://did.cit.jmu.edu/. Secondly, the Borough of Manhattan Community College (BMCC), one of the campuses of the City University of New York, set up a project to stream video and audio content to make their physical video and DVD collection more accessible after hours and to extend their electronic reserves service. Their initial goal was to create digital archives copies of high use videos in their collection and to stream these to the classroom. The project then developed into making streams available on demand to students. The BMCC decided to place links to streamed videos on their electronic reserves site, ERes (Eng & Hernandez, 2006). This was in order to comply with the US TEACH Act which allows educational institutions to use copyright protected materials for distance education. Links were placed on course pages administered by lecturers and access limited to students enrolled in those courses by username and password. 8 The third example is The Northern Lakes College in north-central Alberta, Canada. The College has made around 350 digital videos available to students at distant locations of Northern Lakes College (Prosser, 2006). Initially the software used to mount and acquire titles was Media on Demand (MonD) which allowed the media to be shown from the desktop. However, the College has since discovered that MonD was not going to be compatible with Microsoft Vista, so have moved all 650 or so video streaming titles to the catalogue. Prosser states “It wasn’t a seamless process, but I think this has been a good thing because now content is collected in one place regardless of format.” (Prosser, personal communication, Nov 15, 2008) Conclusion The Curtin video supplier survey and subsequent investigations and literature searching have provided a much clearer picture of the challenges and opportunities inherent in making streamed video content available to Curtin University staff and students. We now have a rich array of options available to us: to continue to provide access to streamed content on request but for the library to host this content; to digitize high use items in the Library’s audiovisual collections when permission can be obtained, to actively seek out sources of free digital content and make these available on our website; to subscribe to a collection of streamed content such as PBS or FMG or to subscribe to vendor collections such as TV News. We may also adopt a blend of these options. Enthusiasm from academics has certainly been demonstrated and the streaming video infrastructure is also very developed at Curtin. Is video streaming in fact, “an overdue Library service” (Clark, 2005), one in which Australian universities appear to be lagging behind? Appendix 1 - Sources of digital video Europe SourceLearn https://www.sourcelearn.com/about.asp https://www.sourcelearn.com/about.asp UK Lifesign (http://www.lifesign.ac.uk), Click and Go Video'(http://www.clickandgovideo.ac.uk/) and Diverse (http://www.sar.bolton.ac.uk/diverse/). US Annenberg Media Learner.org http://www.learner.org/ Discovery Education http://www.discoveryeducation.com/products/streaming/ Research Channel http://www.researchchannel.org/prog/ FMG http://ffh.films.com/ PBS http://www.pbs.org/ WGBH http://openvault.wgbh.org/ New Day Films http://www.newdaydigital.com/ Google Video http://video.google.com.au/?hl=en&tab=wv The Internet Archive http://www.archive.org/index.php TED http://www.ted.com/ 9 Australia VOCAM Online Safety Videos http://www.vocam.com/products/vocamonlinedvds/solution.aspx?vdo=promotion&sol =vocamonlinedvds ABC Video on Demand http://www.abc.net.au/vod/ Tape Services http://www.tapeservices.sa.edu.au/ Enhance TV www.enhancetv.com.au/ The Learning Federation develops digital curriculum content for all Australian and New Zealand schools. The project is a collaborative initiative of all Australian and New Zealand governments. http://www.thelearningfederation.edu.au/default.asp Bibliography Alberico, R. (2007). Developing video streaming service across campuses: the VIVA experience. In EDUCAUSE Australasia, April 29 - May 2, 2007 Melbourne, Australia. Albertico, R. (2008, June 11). Developing a Statewide Video Streaming Service for Higher Education. Paper presented at the 2008 NMC Summer Conference, Princeton University, New Jersey. Australian Copyright Council. (December, 2006). Videos and DVD's : copying & downloading [Information Sheet G026]. Boeke, C. (2004). Streaming in Digital Libraries: A Survey of Current Trends and Applications. LBSC Fall ’04. Available from: fedlinksurvey.pbwiki.com/f/StreamingSurveyPaperBoekeFall04.pdf Clark, J., Maxfield, S., & Saunders, B. (2005). Online Video Collections: Transition from Media Checkout to Media Streaming. Paper presented at the Educause Annual Conference, Orlando. Eng, S., & Hernandez, F. A. (2006). Managing streaming video: A new role for technical services. Library Collections, Acquisitions, and Technical Services, 30(3-4), 214-223. Engilman, W. D., Cox, T. H., Bednar, E. D., & Proffit, W. R. (2007). Equipping orthodontic residency programs for interactive distance learning. American Journal of Orthodontics and Dentofacial Orthopedics, 131(5), 651-655. Retrieved 20 October, 2008, from Web of Knowledge database. Hahm, J. S., Lee, H. L., Kim, S. I., Shimizu, S., Choi, H. S., Ko, Y., et al. (2007). A remote educational system in medicine using digital video. HepatoGastroenterology, 54(74), 373-376. Retrieved 20 October, 2008, from Web of Knowledge database. Mullins-Dove, T. G. (2006). Streaming Video and Distance Education. Distance Learning, 3(4), 63. Retrieved 20 October, 2008, from ProQuest database. Prosser, H. (2006). Video streaming in the Wild West. Partnership : the Canadian Journal of Library and Information Practice and Research, 1(1), 1-9. 10 Ranaldo, N., Rapuano, S., Riccio, M., & Zoino, F. (2007). Remote control and video capturing of electronic instrumentation for distance learning. Ieee Transactions on Instrumentation and Measurement, 56(4), 1419-1428. Retrieved 20 October, 2008, from Web of Knowledge database. Ross, J. (2005). STREAMING VIDEO: Why to Do It, How to Do It, and Where to Get It. MultiMedia & Internet@Schools, 12(5), 9. Shephard, K. (2003). Questioning, promoting and evaluating the use of streaming video to support student learning. British Journal of Educational Technology, 34(3), 295-308. Strom, J. (2002, May). Streaming Video: Overcoming Barriers for Teaching and Learning. Paper presented at the International Symposium on Educational Conferencing Banff, Canada. 11