Environmental Conditions, Resources, and Conflicts

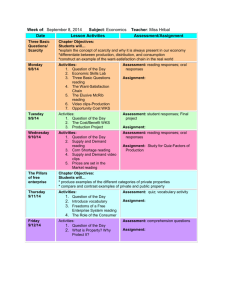

advertisement