A Teaching Case Study - Foundation for Child Development

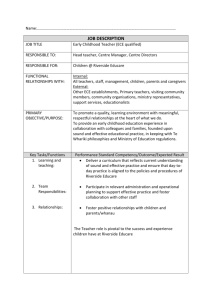

advertisement