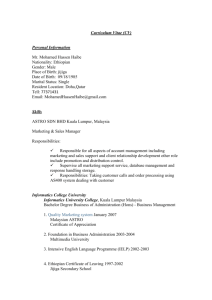

CONSTRUCTION PROJECTS NOR HAYATI BINTI IBRAHIM

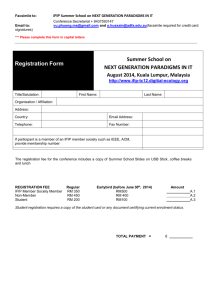

advertisement