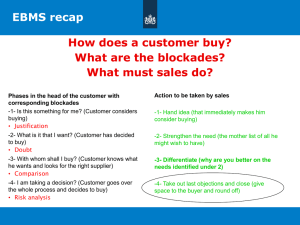

Consumer And Organisational Buyer Behaviour 3

advertisement