Contracts-wilkinsonryan-2011-concise

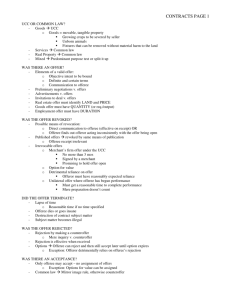

advertisement