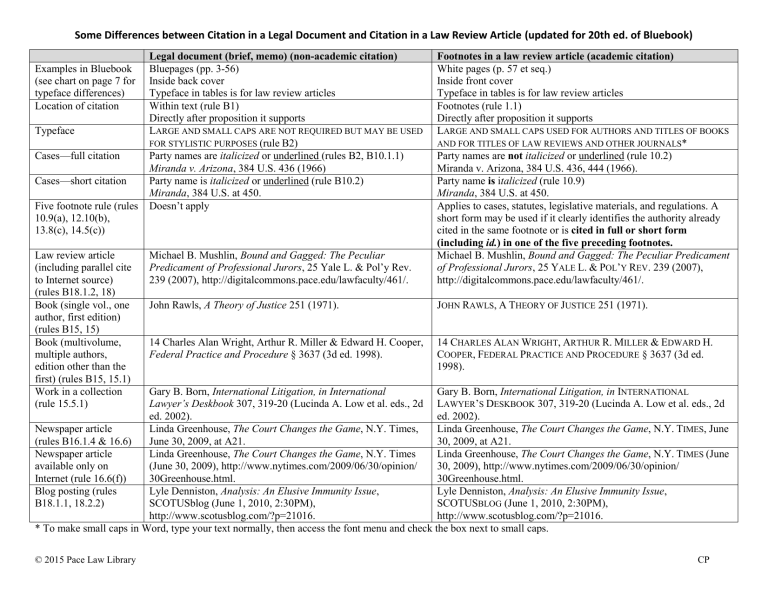

Some Differences between Citation in a Legal Document and

advertisement

Some Differences between Citation in a Legal Document and Citation in a Law Review Article (updated for 20th ed. of Bluebook) Examples in Bluebook (see chart on page 7 for typeface differences) Location of citation Typeface Cases—full citation Cases—short citation Five footnote rule (rules 10.9(a), 12.10(b), 13.8(c), 14.5(c)) Law review article (including parallel cite to Internet source) (rules B18.1.2, 18) Book (single vol., one author, first edition) (rules B15, 15) Book (multivolume, multiple authors, edition other than the first) (rules B15, 15.1) Work in a collection (rule 15.5.1) Legal document (brief, memo) (non-academic citation) Bluepages (pp. 3-56) Inside back cover Typeface in tables is for law review articles Within text (rule B1) Directly after proposition it supports LARGE AND SMALL CAPS ARE NOT REQUIRED BUT MAY BE USED FOR STYLISTIC PURPOSES (rule B2) Party names are italicized or underlined (rules B2, B10.1.1) Miranda v. Arizona, 384 U.S. 436 (1966) Party name is italicized or underlined (rule B10.2) Miranda, 384 U.S. at 450. Doesn’t apply Michael B. Mushlin, Bound and Gagged: The Peculiar Predicament of Professional Jurors, 25 Yale L. & Pol’y Rev. 239 (2007), http://digitalcommons.pace.edu/lawfaculty/461/. Footnotes in a law review article (academic citation) White pages (p. 57 et seq.) Inside front cover Typeface in tables is for law review articles Footnotes (rule 1.1) Directly after proposition it supports LARGE AND SMALL CAPS USED FOR AUTHORS AND TITLES OF BOOKS AND FOR TITLES OF LAW REVIEWS AND OTHER JOURNALS* Party names are not italicized or underlined (rule 10.2) Miranda v. Arizona, 384 U.S. 436, 444 (1966). Party name is italicized (rule 10.9) Miranda, 384 U.S. at 450. Applies to cases, statutes, legislative materials, and regulations. A short form may be used if it clearly identifies the authority already cited in the same footnote or is cited in full or short form (including id.) in one of the five preceding footnotes. Michael B. Mushlin, Bound and Gagged: The Peculiar Predicament of Professional Jurors, 25 YALE L. & POL’Y REV. 239 (2007), http://digitalcommons.pace.edu/lawfaculty/461/. John Rawls, A Theory of Justice 251 (1971). JOHN RAWLS, A THEORY OF JUSTICE 251 (1971). 14 Charles Alan Wright, Arthur R. Miller & Edward H. Cooper, Federal Practice and Procedure § 3637 (3d ed. 1998). 14 CHARLES ALAN WRIGHT, ARTHUR R. MILLER & EDWARD H. COOPER, FEDERAL PRACTICE AND PROCEDURE § 3637 (3d ed. 1998). Gary B. Born, International Litigation, in International Gary B. Born, International Litigation, in INTERNATIONAL Lawyer’s Deskbook 307, 319-20 (Lucinda A. Low et al. eds., 2d LAWYER’S DESKBOOK 307, 319-20 (Lucinda A. Low et al. eds., 2d ed. 2002). ed. 2002). Newspaper article Linda Greenhouse, The Court Changes the Game, N.Y. Times, Linda Greenhouse, The Court Changes the Game, N.Y. TIMES, June (rules B16.1.4 & 16.6) June 30, 2009, at A21. 30, 2009, at A21. Newspaper article Linda Greenhouse, The Court Changes the Game, N.Y. Times Linda Greenhouse, The Court Changes the Game, N.Y. TIMES (June available only on (June 30, 2009), http://www.nytimes.com/2009/06/30/opinion/ 30, 2009), http://www.nytimes.com/2009/06/30/opinion/ Internet (rule 16.6(f)) 30Greenhouse.html. 30Greenhouse.html. Blog posting (rules Lyle Denniston, Analysis: An Elusive Immunity Issue, Lyle Denniston, Analysis: An Elusive Immunity Issue, B18.1.1, 18.2.2) SCOTUSblog (June 1, 2010, 2:30PM), SCOTUSBLOG (June 1, 2010, 2:30PM), http://www.scotusblog.com/?p=21016. http://www.scotusblog.com/?p=21016. * To make small caps in Word, type your text normally, then access the font menu and check the box next to small caps. © 2015 Pace Law Library CP Comparison of Text with Citations in a Legal Document to the Same Text with Citations in a Law Review Article In a legal document: In a law review article: The Fifth Amendment protects the rights of an individual against selfincrimination. U.S. Const. amend. V. The Supreme Court has held that “the prosecution may not use statements, whether exculpatory or inculpatory, stemming from custodial interrogation of the defendant unless it demonstrates the use of procedural safeguards effective to secure the privilege against self-incrimination.” Miranda v. Arizona, 384 U.S. 436, 444 (1966). Therefore, police are required to give Miranda warnings prior to interrogating a suspect in order to protect the suspect’s Fifth Amendment right against self-incrimination. See Brandon L. Garrett, Judging Innocence, 108 Colum. L. Rev. 55, 90 (2008). In addition, the Fifth Amendment’s protection against selfincrimination extends “outside of criminal court proceedings and serves to protect persons in all settings in which their freedom of action is curtailed in any significant way from being compelled to incriminate themselves,” Miranda, 384 U.S. at 467, and trial courts are required to exclude involuntary confessions from the trial, see Garrett, supra, at 90. This privilege against self-incrimination “can be asserted in any proceeding, civil or criminal, administrative or judicial, investigatory or adjudicatory.” Kastigar v. United States, 406 U.S. 441, 444 (1972). However, a grand jury witness granted immunity “may not refuse to comply with the order [to testify] on the basis of his privilege against self-incrimination.” Id. at 448; 18 U.S.C. § 6002 (2012). The Fifth Amendment protects the rights of an individual against selfincrimination.1 The Supreme Court has held that “the prosecution may not use statements, whether exculpatory or inculpatory, stemming from custodial interrogation of the defendant unless it demonstrates the use of procedural safeguards effective to secure the privilege against selfincrimination.”2 Therefore, police are required to give Miranda warnings prior to interrogating a suspect in order to protect the suspect’s Fifth Amendment right against self-incrimination.3 In addition, the Fifth Amendment’s protection against self-incrimination extends “outside of criminal court proceedings and serves to protect persons in all settings in which their freedom of action is curtailed in any significant way from being compelled to incriminate themselves,”4 and trial courts are required to exclude involuntary confessions from the trial.5 This privilege against self-incrimination “can be asserted in any proceeding, civil or criminal, administrative or judicial, investigatory or adjudicatory.”6 However, a grand jury witness granted immunity “may not refuse to comply with the order [to testify] on the basis of his privilege against self-incrimination.”7 Use [ ] to indicate inserted material within a quotation. (rule 5.2(a)) © 2015 Pace Law Library -------------------------------1 U.S. CONST. amend. V. Miranda v. Arizona, 384 U.S. 436, 444 (1966). 3 See Brandon L. Garrett, Judging Innocence, 108 COLUM. L. REV. 55, 90 (2008). 4 Miranda, 384 U.S. at 467. 5 See Garrett, supra note 3, at 90. 6 Kastigar v. United States, 406 U.S. 441, 444 (1972). 7 Id. at 448; 18 U.S.C. § 6002 (2012). 2 CP