Anatomy and Physiology of the Elasmobranch Olfactory System

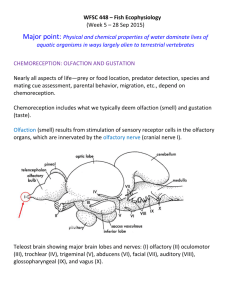

advertisement