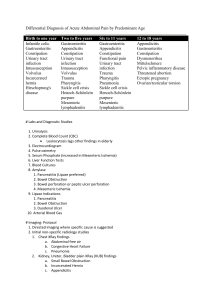

R e s i d e n t s ’ S e c t i o n • S t r u c t u r e d R ev i ew

McLaughlin et al.

Mesenteric Panniculitis and Its Mimics

Downloaded from www.ajronline.org by 198.108.143.18 on 08/15/14 from IP address 198.108.143.18. Copyright ARRS. For personal use only; all rights reserved

Residents’ Section

Structured Review

Residents

inRadiology

Patrick D. McLaughlin1,2

Antonella Filippone 3

Michael M. Maher 1,2

McLaughlin PD, Filippone A, Maher MM

Keywords: mesenteric panniculitis, mesentery, retractile

mesenteritis, sclerosing mesenteritis

DOI:10.2214/AJR.12.8493

Received December 22, 2011; accepted after revision

June 6, 2012.

1

Department of Radiology, Cork University Hospital,

Wilton, Cork, Munster, Eire, Ireland. Address

correspondence to M. M. Maher (m.maher@ucc.ie). 2

Department of Radiology, University College Cork,

Cork, Ireland.

3

Department of Neurosciences and

Imaging,Section of Radiological Imaging,

“G.d’Annunzio”University, Chieti, Italy.

WEB

This is a Web exclusive article.

AJR 2013; 200:W116–W123

0361–803X/13/2002–W116

© American Roentgen Ray Society

W116 The “Misty Mesentery”: Mesenteric

Panniculitis and Its Mimics

Key Points

1. The term “misty mesentery” was coined by

Mindelzun et al. in 1996 to describe a regional increase in mesenteric fat density that

is seen frequently at abdominopelvic CT.

2.Mesenteric panniculitis (MP) is one of the

broad range of disorders that may result in the

imaging finding of a misty mesentery on CT.

3. MP cannot be diagnosed on CT without the

exclusion of many other possible causes of

a misty mesentery including disorders that

result in mesenteric edema, lymphedema,

hemorrhage, and infiltration with inflammatory or neoplastic cells.

4. Retractile mesenteritis results in irregular

fibrotic mesenteric masses that simulate

a number of neoplastic conditions of the

mesentery and peritoneum such as carcinoid tumors, desmoid tumors, and peritoneal carcinomatosis.

The term “misty mesentery” was coined

by Mindelzun et al. [1] in 1996 to describe a

regional increase in mesenteric fat density at

abdominopelvic CT. This imaging finding is

commonly encountered during review of abdominal CT scans [2]; when a misty mesentery is observed, the radiologist must consider

many pathologic entities involving the mesenteric fat and adjacent organs that may result in

the infiltration of these tissues by fluid, fibrous

tissue, or inflammatory or neoplastic cells.

Mesenteric panniculitis (MP) is one of

the broad range of disorders that may result

in the imaging finding of a misty mesentery

on CT. MP is pathologically characterized

by inflammation and variable amounts of fibrosis and fat necrosis of the mesentery. Although MP is an important potential cause

for a misty mesentery on CT, MP is a diagnosis that requires the exclusion of a range

of important diseases and ultimately may require histologic confirmation [3].

In this article, we describe the key CT findings associated with MP. We outline the imag-

ing features of MP and of a wider spectrum of

related disorders belonging to the parent group

sclerosing mesenteritis. A misty mesentery can

be seen in association with a range of pathologic entities other than MP. Imaging findings

in conditions known to mimic MP are also described in an attempt to provide the radiologist

with a basis for rational differential diagnosis.

Pathophysiology

MP belongs to a continuum of idiopathic

disorders of the mesentery and peritoneum referred to as “sclerosing mesenteritis” [4]. Pathologically, sclerosing mesenteritis can be divided

into three stages. The first stage is mesenteric

lipodystrophy in which a layer of foamy macrophages replaces the mesenteric fat [4]. The second stage is MP in which there is an infiltrate

of plasma cells, polymorphonuclear leukocytes,

and foamy macrophages [4, 5]. The final stage

is retractile mesenteritis, which is characterized

by collagen deposition, fat necrosis, and fibrosis

that leads to tissue retraction [4, 5].

The cause of sclerosing mesenteritis remains unclear, although several possible

causes have been proposed in the literature including previous abdominal surgery, abdominal trauma, autoimmunity, vasculitis, and infection [6]. Sclerosing mesenteritis has been

associated in a number of case studies with a

variety of intraabdominal and extraabdominal

malignant diseases including lymphoma, colorectal carcinoma, gastric carcinoma, renal

cell carcinoma, melanoma, myeloma, chronic

lymphocytic leukemia, and carcinoid tumors

[6]. Currently, there is no clear answer to the

question of how strongly sclerosing mesenteritis is associated with underlying malignancy.

Kipfer et al. [7] reported that 30% of patients

with sclerosing mesenteritis had an underlying

malignancy, whereas Daskalogiannaki et al.

[6] reported a higher rate of 69% of sclerosing mesenteritis patients with coexisting malignancy. Other investigators have found that

AJR:200, February 2013

Downloaded from www.ajronline.org by 198.108.143.18 on 08/15/14 from IP address 198.108.143.18. Copyright ARRS. For personal use only; all rights reserved

Mesenteric Panniculitis and Its Mimics

the coexistence of malignancy and sclerosing

mesenteritis is not significantly different than

in patients undergoing routine abdominopelvic CT without findings suggesting sclerosing

mesenteritis [8]. The possibility that sclerosing mesenteritis may represent a nonspecific

paraneoplastic response has been suggested,

but available data are limited and the exact relationship between sclerosing mesenteritis and

malignancy remains unclear. There is, however, an established association between sclerosing mesenteritis and other idiopathic inflammatory disorders such as orbital pseudotumor,

retroperitoneal fibrosis, sclerosing cholangitis,

and Reidel thyroiditis [3].

Clinical Characteristics

Sclerosing mesenteritis is reported across

a large age range, typically extending from

the third to the ninth decades. Cases of

sclerosing mesenteritis in the pediatric age

range are rare but have been documented as

case reports in the literature [9]. The most

commonly reported mean age of presentation lies in the seventh decade and a male

preponderance is accepted [4, 7].

Very rarely patients with MP may present

with acute abdominal symptoms including abdominal pain, bloating, nausea, or weight loss

[5], and an abdominal mass may be palpated

in up to 50% of this subgroup [7]. In this subgroup of acutely symptomatic patients, treatment with steroids or a combination of steroids and other drugs such as tamoxifen has

been shown to be beneficial [10]. An increasing proportion of asymptomatic patients continue to be identified when undergoing modern cross-sectional imaging; Daskalogiannaki

et al. [6] reported imaging findings consistent

with MP in 0.6% of 6620 consecutive patients

undergoing routine abdominopelvic CT.

Imaging Findings in Mesenteric

Panniculitis

MP results in a masslike area of heterogeneously increased fat attenuation on CT that

may displace local bowel loops but typically

does not displace the surrounding mesenteric vascular structures [2] (Fig. 1). Ultrasound

may show a well-defined hyperechoic mass

with small central hypoechoic areas or a heterogeneous but predominantly hyperechoic mass [11]. On MRI, a mesenteric mass is

seen with intermediate signal intensity on T1weighted images and with slightly higher signal intensity on T2-weighted images [12]. Mesenteric lymph nodes are often seen within the

region of segmental mesenteric stranding and

nodes may be enlarged to greater than 1 cm in a

small percentage of cases [13]. Approximately

90% of cases involve the small-bowel mesentery [10] and changes are more commonly centered to the left of the midline corresponding

with the jejunal mesentery [14] (Fig. 2).

Important imaging signs of MP include the

“tumoral pseudocapsule” sign (Fig. 3), which

refers to the presence of a peripheral curvilinear band of soft-tissue attenuation limiting

the heterogeneous mesenteric mass from the

surrounding normal mesentery, and the “fat

halo” sign (Fig. 4), which refers to the preservation of normal fat density in the fatty tissue surrounding the mesenteric vessels. The

thickness of the tumoral pseudocapsule band

of soft tissue is typically not greater than 3 mm

[6]. The sensitivities of the fat halo and tumoral pseudocapsule signs were reported as 75%

and 50%, respectively, in a series of 17 pathologically confirmed cases [13]. The specificity

of these signs has not yet been defined to our

knowledge, but radiologists should be aware

that the fat halo sign may also be present in

patients with mesenteric lymphoma [15, 16]

and the tumoral pseudocapsule sign may also

be found in cases of benign and malignant

mesenteric lipomatous tumors [2].

Mimics of Mesenteric Panniculitis

When a misty mesentery is observed on CT,

it is incumbent on the radiologist to consider

and, if possible, exclude alternative causes of a

regional increase in mesenteric fat density such

as edema (Fig. 5), hemorrhage, lymphedema,

inflammation (Fig. 6), and neoplasia (Fig. 7)

before suggesting a diagnosis of MP [1].

Mesenteric Edema

Mesenteric edema may be caused by systemic diseases such as hypoproteinemia or hepatic, cardiac, or renal failure or may be related

to local vascular diseases such as portal hypertension and hepatic, portal, or mesenteric vein

thrombosis. Ascites and fluid in the subcutaneous adipose tissues are not associated with MP;

when these findings are present, the radiologist

should suspect mesenteric edema due to a systemic disease rather than MP. A misty mesentery was identified in 86% of patients with hepatic cirrhosis undergoing abdominal CT [17];

a large number of those patients had evidence

of edema in other adipose compartments but

more than one third of cirrhotic patients may

have evidence of only a misty mesentery.

The pattern of mesenteric edema secondary to mesenteric vein thrombosis tends to be

focal and is typically in continuity with seg-

mental bowel wall thickening, which may indicate the presence of small-bowel ischemia.

Mesenteric Inflammation

Pancreatitis is the most common process associated with inflammation of the small-bowel

mesentery but virtually all other inflammatory diseases of the gastrointestinal tract including cholecystitis, appendicitis, diverticulitis,

inflammatory bowel disease, and infective peritonitis may also result in inflammatory changes

in the adjacent mesentery [3]. Tuberculous peritonitis should be suspected when the following

signs are observed in association with a misty

mesentery [18]: lymphadenopathy with central

hypodensity due to caseous necrosis; nodularity of the mesenteric fat; smooth thickening of

the peritoneum typically with pronounced enhancement; and high-density ascites, which is

proposed to be caused by high protein content.

Mesenteric Hemorrhage

Acute hemorrhage into the small-bowel mesentery typically displays high CT attenuation

values in the range of 40–60 HU. A history of

trauma, anticoagulation therapy, blood dyscrasia, or mesenteric ischemia may be present.

Mesenteric Lymphedema

Primary mesenteric lymphedema, or small

intestinal lymphangiectasia, is a rare disorder

first described in 1961 by Waldmann et al. [19].

Mesenteric lymphedema is associated with

diffuse nodular thickening of the small-bowel

wall resulting from dilated lymphatic channels

within the small-bowel villi. The changes may

be segmental, ascites is usually present, and

small-bowel thickening may assume a stratified appearance due to mucosal or submucosa

edema [20]. Paraaortic and mesenteric lymph

nodes are not usually visible, which may allow differentiation of mesenteric lymphedema from other conditions, such as lymphoma,

Whipple disease, celiac disease, and tuberculosis, all of which can produce diffuse small intestinal wall thickening [21].

Mesenteric Neoplasia

Perhaps the most challenging differential diagnosis to exclude when a misty mesentery is

encountered is early-stage Hodgkin and nonHodgkin lymphoma; lymphoma is the most

common tumor involving the mesentery. Late

stage disease usually presents little diagnostic

difficulty because of the typically bulky mesenteric lymphadenopathy, but early stage disease

can produce mildly enlarged nodes; a misty

mesentery; and, as previously stated, even the

AJR:200, February 2013W117

Downloaded from www.ajronline.org by 198.108.143.18 on 08/15/14 from IP address 198.108.143.18. Copyright ARRS. For personal use only; all rights reserved

McLaughlin et al.

fat halo sign [15, 16]. Any additional lymphadenopathy seen outside the mesenteric region,

particularly in the retroperitoneum, should immediately raise suspicion for early stage lymphoma [2]. Radiologists should recognize that

treatment response after chemotherapy may

also result in high-density changes in the mesenteric fat that can be indistinguishable from

MP [8] despite an improvement in or even resolution of the mesenteric lymphadenopathy.

Primary mesenteric neoplasms, such as neurofibromas, lipomas, and mesenteric liposarcomas, can mimic MP and may also display a

curvilinear rim of soft tissue surrounding their

peripheral margins mimicking the previously

described tumoral pseudocapsule sign [2]. An

imaging finding that can help in distinguishing

these rare neoplasms from MP and other benign pathologic processes is visible mass effect

on adjacent mesenteric vessels [8]. Mass effect

is not a feature of MP, and in such cases, imaging-guided percutaneous biopsy or laparoscopy and biopsy should be considered.

Imaging Findings in Retractile

Mesenteritis

Retractile mesenteritis represents the more

chronic and fulminant subgroup of sclerosing

mesenteritis [4]. Its imaging characteristics differ greatly from those of the MP subgroup and

are typified by the presence of one or more irregular fibrotic soft-tissue mesenteric masses

(Fig. 8). Calcification may be seen within the

soft-tissue mass, most likely reflecting a sequela

of fat necrosis, and there may be encasement

of the adjacent bowel loops and vascular structures, leading to signs of obstruction and occasionally to hollow visceral ischemia [13, 22].

on CT, but the primary carcinoid tumor, most

commonly involving the ileum, may not be

detectable on CT. Small-bowel investigations

such as CT enterography, CT enteroclysis, or

double-balloon and capsule endoscopy are frequently required to detect the small primary tumors [3]. Desmoid tumors constitute a benign

proliferation of fibrous tissue and are seen in

association with familial colorectal polyposis,

otherwise known as Gardner syndrome, most

commonly after laparotomy or in the postpartum patient [2]. Most mesenteric desmoid tumors are isoattenuating relative to muscle.

Mesenteric vessels are usually displaced but

not encased by the mass [2].

When retractile mesenteritis involves the

omentum or peripancreatic region, it may

simulate widespread carcinomatosis; infection; or, rarely, pancreatic malignancy [23].

Conclusion

Radiologists should be aware that sclerosing

mesenteritis has two imaging phenotypes—

namely, MP and retractile mesenteritis. MP results in a segmental increase in mesenteric fat

density termed the “misty mesentery”; however, this imaging finding is nonspecific and MP

cannot be diagnosed on CT without the exclusion of a range of important differential diagnoses that can mimic MP on imaging studies,

including causes of mesenteric edema, lymphedema, hemorrhage, or infiltration. Retractile

mesenteritis results in irregular fibrotic mesenteric masses and therefore simulates neoplastic conditions of the mesentery and peritoneum

such as carcinoid tumors, desmoid tumors, and

peritoneal carcinomatosis.

References

Mimics of Retractile Mesenteritis

The imaging features of retractile mesenteritis overlap with numerous malignant conditions

of the mesentery and peritoneum such as carcinoid tumors, desmoid tumors, and peritoneal

carcinomatosis [2]. Because of the overlapping

imaging findings in these conditions, retractile

mesenteritis is also a diagnosis of exclusion and

typically requires extensive histologic sampling

and often resection to exclude neoplasia [3].

Gastrointestinal carcinoid tumors typically appear as a solid mass located in the mesentery with imaging features of a surrounding

desmoplastic reaction resulting in stellate linear stranding of the adjacent mesenteric tissues

[2] (Fig. 9). Calcifications are visible in up to

70% of these lesions and they are often indistinguishable from retractile mesenteritis on CT.

The mesenteric mass is often easily identified

W118

1.Mindelzun RE, Jeffrey RB Jr, Lane MJ, Silverman PM. The misty mesentery on CT: differential

diagnosis. AJR 1996; 167:61–65

2.Filippone A, Cianci R, Di Fabio F, Storto ML.

Misty mesentery: a pictorial review of multidetector-row CT findings. Radiol Med 2011; 116:351–365

3.Horton KM, Lawler LP, Fishman EK. CT findings

in sclerosing mesenteritis (panniculitis): spectrum

of disease. RadioGraphics 2003; 23:1561–1567

4.Emory TS, Monihan JM, Carr NJ, Sobin LH.

Sclerosing mesenteritis, mesenteric panniculitis

and mesenteric lipodystrophy: a single entity? Am

J Surg Pathol 1997; 21:392–398

5.Vlachos K, Archontovasilis F, Falidas E, Mathioulakis S, Konstandoudakis S, Villias C. Sclerosing

mesenteritis: diverse clinical presentations and

dissimilar treatment options—a case series and

review of the literature. Int Arch Med 2011; 4:17

6.Daskalogiannaki M, Voloudaki A, Prassopoulos

P, et al. CT evaluation of mesenteric panniculitis:

prevalence and associated diseases. AJR 2000;

174:427–431

7.Kipfer RE, Moertel CG, Dahlin DC. Mesenteric

lipodystrophy. Ann Intern Med 1974; 80:582–588

8.

van Breda Vriesman AC, Schuttevaer HM,

Coerkamp EG, Puylaert JB. Mesenteric panniculitis: US and CT features. Eur Radiol 2004;

14:2242–2248

9.Sampert C, Lowichik A, Rollins M, Inman C,

Bohnsack J, Pohl JF. Sclerosing mesenteritis in a

child with celiac disease. J Pediatr Gastroenterol

Nutr 2011; 53:688–690

10.Akram S, Pardi DS, Schaffner JA, Smyrk TC. Sclerosing mesenteritis: clinical features, treatment, and

outcome in ninety-two patients. Clin Gastroenterol

Hepatol 2007; 5:589–596; quiz, 523–524

11.Catalano O, Cusati B. Sonographic detection of

mesenteric panniculitis: case report and literature

review. J Clin Ultrasound 1997; 25:141–144

12.Kakitsubata Y, Umemura Y, Kakitsubata S, et al.

CT and MRI manifestations of intraabdominal

panniculitis. J Clin Imaging 1993; 17:186–188

13.Sabate J, Torrubia S, Maideu J. Sclerosing mesenteritis: imaging findings in 17 patients. AJR 1999;

172:625–629

14.Seo BK, Ha HK, Kim AY, et al. Segmental misty

mesentery: analysis of CT features and primary

causes. Radiology 2003; 226:86–94

15.Yenarkarn P, Thoeni RF, Hanks D. Case 107:

lymphoma of the mesentery. Radiology 2007;

242:628–631

16.Zissin R, Metser U, Hain D, Even-Sapir E. Mesenteric panniculitis in oncologic patients: PET-CT

findings. Br J Radiol 2006; 79:37–43

17.Chopra S, Dodd GD, Chintapalli KN, Esola CC,

Ghiatas AA. Mesenteric, omental, and retroperitoneal edema in cirrhosis: frequency and spectrum

of CT findings. Radiology 1999; 211:737–742

18.Akhan O, Pringot J. Imaging of abdominal

tuberculosis. Eur Radiol 2002; 12:312–323

19.Waldmann TA, Steinfeld JL, Dutcher TF, Davidson J, Gordon R Jr. The role of the gastrointestinal

system in “idiopathic hypoproteinemia.” Gastroenterology 1961; 41:197–207

20.Simpson AJ, Amer H. The radiology corner: segmental lymphangiectasia of the small bowel. Am J

Gastroenterol 1979; 72:95–100

21.Horton KM, Corl FM, Fishman EK. CT of nonneoplastic diseases of the small bowel: spectrum of

disease. J Comput Assist Tomogr 1999; 23:417–428

22.Hassan T, Balsitis M, Rawlings D, Shah AA. Sclerosing mesenteritis presenting with complete

small bowel obstruction, abdominal mass and hydronephrosis. Ir J Med Sci 2012; 181:393–395

23. Scudiere JR, Shi C, Hruban RH, et al. Sclerosing mesenteritis involving the pancreas: a mimicker of pancreatic cancer. Am J Surg Pathol 2010; 34:447–453

AJR:200, February 2013

Downloaded from www.ajronline.org by 198.108.143.18 on 08/15/14 from IP address 198.108.143.18. Copyright ARRS. For personal use only; all rights reserved

Mesenteric Panniculitis and Its Mimics

A

B

Fig. 1—47-year-old man with masslike region of heterogeneously increased fat attenuation consistent with mesenteric panniculitis.

A and B, Axial contrast-enhanced CT images show fatty mass (arrow) displacing local bowel loops but not displacing surrounding mesenteric vascular structures.

Bilateral extra renal pelves are also incidentally shown.

A

B

C

D

Fig. 2—75-year-old man with mesenteric panniculitis.

A and B, Axial contrast-enhanced CT images show involvement of jejunal mesentery (arrow) that initially is located on left side of abdomen.

C and D, Axial contrast-enhanced CT images acquired at later date show involvement of jejunal mesentery (arrow) persists but has moved in interim to right side of abdomen.

AJR:200, February 2013W119

Downloaded from www.ajronline.org by 198.108.143.18 on 08/15/14 from IP address 198.108.143.18. Copyright ARRS. For personal use only; all rights reserved

McLaughlin et al.

A

B

Fig. 3—60-year-old man with mesenteric panniculitis.

A and B, Axial contrast-enhanced CT images show peripheral curvilinear band of soft-tissue attenuation (arrows), limiting heterogeneous mesenteric mass from

surrounding normal mesentery. This finding is referred to as “tumoral pseudocapsule” sign.

Fig. 4—63-year-old man with mesenteric

panniculitis. Axial contrast-enhanced CT image

shows preservation of normal fat density in tissues

surrounding mesenteric vessels (arrows), thereby

creating “fat halo” sign.

A

B

Fig. 5—58-year-old man with acute superior mesenteric venous thrombosis.

A and B, Axial CT images show filling defect (arrow, A) in superior mesenteric vein with associated regional increase in mesenteric fat density as result of edema. There

also is moderate volume of ascites (arrowheads).

W120

AJR:200, February 2013

Downloaded from www.ajronline.org by 198.108.143.18 on 08/15/14 from IP address 198.108.143.18. Copyright ARRS. For personal use only; all rights reserved

Mesenteric Panniculitis and Its Mimics

A

B

Fig. 6—Mesenteric inflammation as mimic of mesenteric panniculitis (MP).

A and B, Axial (A) and coronal (B) contrast-enhanced CT images of 43-year-old

man with acute pancreatitis show local increase in mesenteric fat density and

mild adenopathy (arrow, A) secondary to inflammation. Pancreas appears normal

on CT but presence of ascites (arrowheads, B) and retroperitoneal fluid is strongly

suggestive of diagnosis other than MP.

C, Axial contrast-enhanced CT image of 28-year-old woman with acute appendicitis

(arrow) shows local increase in mesenteric fat density secondary to inflammation.

C

AJR:200, February 2013W121

Downloaded from www.ajronline.org by 198.108.143.18 on 08/15/14 from IP address 198.108.143.18. Copyright ARRS. For personal use only; all rights reserved

McLaughlin et al.

A

B

C

D

Fig. 7—78-year-old man with non-Hodgkin lymphoma.

A and B, Axial (A) and coronal (B) contrast-enhanced CT images acquired at initial diagnosis show multiple pathologically enlarged mesenteric lymph nodes (arrow).

C and D, Axial (C) and coronal (D) contrast-enhanced CT images acquired after successful treatment with chemotherapy show previously enlarged mesenteric

lymph nodes are now smaller; however, residual heterogeneously increased mesenteric fat attenuation (arrowhead) after therapy mimics appearance of mesenteric

panniculitis.

W122

AJR:200, February 2013

Downloaded from www.ajronline.org by 198.108.143.18 on 08/15/14 from IP address 198.108.143.18. Copyright ARRS. For personal use only; all rights reserved

Mesenteric Panniculitis and Its Mimics

A

B

Fig. 8—43-year-old woman with retractile mesenteritis.

A, Axial contrast-enhanced CT image shows irregular, poorly circumscribed mesenteric soft-tissue mass (arrow), which is inseparable from terminal ileum, and punctate

foci of calcification likely representing internal fat necrosis.

B, Coronal contrast-enhanced CT image shows irregular, poorly circumscribed mesenteric soft-tissue mass (arrow).

A

B

Fig. 9—58-year-old man with carcinoid tumor of distal ileum.

A, Axial contrast-enhanced CT image shows solid mesenteric mass with internal calcification (arrow) closely resembling appearance of retractile mesenteritis.

B, Coronal contrast-enhanced CT image shows solid mesenteric mass (arrow) closely resembling appearance of retractile mesenteritis.

AJR:200, February 2013W123

![Paper_Prof_Wang_final1[1]](http://s3.studylib.net/store/data/005836194_1-85fb8d8882c087decd1a6d9c9fdc99c0-300x300.png)