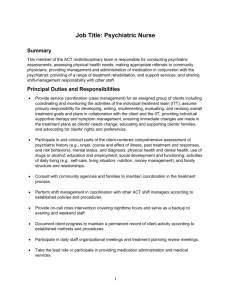

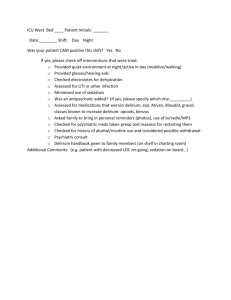

Acute Psychiatric Management - HETI

advertisement