(1992). Short-term memory at the turn of the century

advertisement

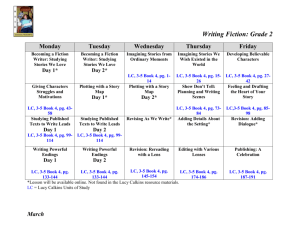

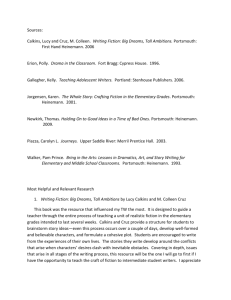

Historical Lessons in the Science of Psychology Short-Term Memory at the Turn of the Century Mary Whiton Calkins's Memory Research Stephen Madigan and Ruth O'Hara University of Southern California Mary Whiton Calkins (1863-1930) is often mentioned in accounts of the history of memory research as the inventor of the method of paired associates as well as for her investigations of primacy, recency, frequency, and vividness in association formation. Her experimental studies over the period from 1892 to 1894 not only introduced the paired associates method but were also pioneering investigations of immediate memory that led Calkins to identify modality effects, primacy and recency effects, and a number of other phenomena rediscovered many years later. Calkins's work deserves more recognition in historical accounts of the early years of experimental psychology and memory research. The purpose of this article is to draw attention to some interesting and largely unknown aspects of Mary Whiton Calkins's (1863-1930) work on association and memory. Accounts of the early years of experimental psychology commonly refer to her studies of primacy, recency, frequency, and vividness as well as to her introduction of the paired associates method (Cofer, 1979; Newman, 1987; Postman, 1985). Calkins's articles describing this research in fact contained much more than reports of the effects of the four factors affecting associability. A detailed examination of her experimental procedures and data reveals that she reported many experimental effects that were rediscovered and recognized as fundamental much later. Among her findings, using modern names for them, were modality effects in immediate recall; recency effects and the influence of interpolated events on recency effects; intraserial repetition; negative recency effects; output interference; and unlearning effects. Readers may be familiar with Calkins as the first woman to serve as president of the American Psychological Association (APA) in 1905; also, she has been included in recent accounts of the careers of women in psychology. Biographical information about Calkins can be found in her own statement (Calkins, 1930) and in Furumoto (1979) and Scarborough and Furumoto (1987). In this article we will focus on the purpose, methodology, and results of her research. The biographical details are drawn mostly from Scarborough and Furumoto's account 170 of Calkins's status and studies at Harvard over the period from 1890 to 1894. The Research Setting Calkins, with a Smith College undergraduate degree, was hired by Wellesley College in 1887 as an instructor of Greek. She was encouraged by the college to obtain advanced training in psychology with a view to assuming a newly created position in that subject. Despite policies that excluded women from graduate programs, Calkins was finally able to join William James's graduate seminar in the fall of 1890, pursuing at the same time training in laboratory practices with Edmund Sanfbrd at Clark University in 1891—1892. However, this graduate training was not undertaken as an officially admitted graduate student, nor was her work and study with Hugo Miinsterburg in 1892-1894, which formed the basis of her research and publications on association and memory. Calkins's research initially appeared in the first volume of Psychological Review in the form of a brief report describing a research program "undertaken as an attempt to answer experimentally the question of the relative significance of frequency, vividness, recency, and earliness as conditions of association" (Calkins, 1894, p. 476). This was followed by a second brief report (Calkins, 1896a) and then by a more detailed theoretical and experimental treatment (Calkins, 1896b). The purpose of the experimental studies was to "supplement the purely introspective study of the nature of association by describing in relatively concrete terms the probable direction of trains of associated images" (Calkins, 1896b, p. 35). The first 34 pages of this article dealt with the causes and course of association, with special emphasis on the distinction between the objects of consciousness and the contents of consciousness. These two terms correspond fairly closely to cue and to-be-remembered item in current memory research terminology. In Calkins's usage, an object of consciousness was a percept; the contents of consciousness were the stored associations evoked by the object. AICorrespondence concerning this article should be addressed to Stephen Madigan, Department of Psychology, University of Southern California, Los Angeles, CA 90089-1061. February 1992 • American Psychologist Copyright 1992 by the American Psychological Association, Inc. 0003-066X/92/S2.00 Vol.47, No. 2, 170-174 though the specifics of the association theory to which she devoted considerable space have little contemporary interest, the objects-contents distinction does because it appears to be directly responsible for the basic experimental tool she devised—the method of paired associates. The Paired Associates Method We say "appears to be directly responsible" because one of the curious aspects of Calkins's 1894 and 1896 articles is that there was in them not one word of rationalization of the method. For Calkins it may have been a simple and direct way of realizing the objects-contents in a fashion that could not be done with serial learning methods. We should note here too that although Calkins was apparently thefirstsystematically to use and report a paired associates methodology, she did not use the term paired associates. In fact she used no name at all for the procedure in her experimental reports. The attribution of the term method of right associates to Calkins (Stevens & Gardner, 1982, p. 83) is incorrect; Calkins used that term only in her autobiographical statement some 30 years later (Calkins, 1930). The earliest use of the term paired associate that we have been able tofindin English is by Thoradike (1908), who did not cite Calkins's studies or methods. The Experiments Calkins's 1894 and 1896 articles reported the results of several independent experiments with about 60 subjects and 2,200 study-test trials in all. The basic procedure was to present lists of from 7 to 12 paired associate items, the cue items being color names or three-letter nonsense syllables and the response items being two- or three-digit numbers. Auditory and visual presentation were used in different studies. Calkins's procedure was essentially a single-trial paired associates procedure, identical in all important respects to the methods described by Murdock (1974) and others. Rather than using a probe technique to test a single pair per list, Calkins typically tested every item presented, usually with an immediate test but sometimes with a "filled interlude" between presentation and testing. With this basic research tool Calkins set out to study the influence of four characteristics of an object of consciousness that might influence the readiness with which the object called some specific contents to mind. These were primacy, recency, frequency, and vividness. Her methodology involved within-list or within-sequence contrasts. For example, to study the effects of frequency, Calkins constructed lists in which a pair, such as WEZ31, might occur two or three times, whereas another pair, such as WEZ-47, might occur once, all in the same list. Similarly, to study recency, Calkins used sequences in which pairs such as WEZ-39 and WEZ-31 occurred in the same list, one in the last or second-to-the last serial position, and one earlier. Calkins used an additional procedure that extended the obvious parallel with the retroactive interference (AB-AC) paradigm: She required subjects to attempt recall of both of the response items February 1992 • American Psychologist in any order to the stimulus or cue item, a procedure later called the modified modified free recall (MMFR) test (Barnes & Underwood, 1954). Table 1 shows an example of one of Calkins's lists, consisting of color-number pairs and designed to study frequency effects. In her experiments subjects were tested with several such sequences, each differing in the variable studied. For example, some sequences had vivid as opposed to ordinary pairings, some sequences had more and less recent pairings, and so on. The Results Calkins's main finding concerning the influence of primacy, recency, frequency, and vividness was that frequency was by far the strongest influence: In general, a repeated pairing overrode the influence of a vivid one or a recent one. The effect was strong enough to suggest to her a mental hygiene application: "The prominence of frequency is of course of grave importance, for it means the possibility of exercising some control over the life of the imagination, and of definitely combatting harmful or troublesome associations" (1896b, p. 56). Calkins's findings concerning other contrasts, such as primacy versus vividness, led to no such clear-cut conclusions. However, in discussing her data Calkins made a number of interesting observations of effects that were peripheral to the primacy-recency-frequency-vividness issue but of considerable interest to contemporary memory theory. The following are among the more noteworthy observations made by Calkins. Recency Effects Calkins explicitly recognized the nature of the short-term recency effect in several ways. One was to arrange test sequences so that the last pair in a list was never tested first, her rationale being a sensory-memory consideration: "The recent color . . . was placed second, not first, in Table 1 Example of Calkins's (1896)Experimental Materials: Paired Associate List to Test Frequency Effects Study series Serial position 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 Test series Color Number Color Green Brown Violet Light grey Violet Orange Blue Violet Medium grey Violet Light green Strawberry 47 73 26 58 61 84 12 61 39 61 78 52 Blue Light grey Strawberry Green Violet Orange Brown Medium grey Light green 171 the test series so that no after-image of the numeral might remain" (1896b, p. 44). Calkins also clearly identified the effects of interpolated events (test trials in this case) on recency effects: "The swiftly decreasing influence of recency . . . is thus clearly indicated: even the intervention of only two colors between the last combination of color and numeral was sufficient to annihilate the effect of recency" (p. 45). Interestingly, Calkins did not refer to James's concept of primary memory in this connection even though her description of recency effects seems very close to this concept. Figure 1 Serial Position Effects and the Negative Recency Effect in Immediate (I) and Delayed (D) Recall 100 Calkms (1898) o I 80-- o—o o Modality Effects The second of Calkins's two sets of experiments involved auditory rather than visual presentation, with pairs of nonsense syllables and numbers. Her comparisons of results with the visual series in the first experiment led her to observe that "the records of the recency experiments show the very striking effect of auditory recency" (1896b, p. 50). Just as later research showed the restriction of modality effects to an auditory superiority for recent items (Murdock, 1974), so Calkins found that visual and auditory series seemed essentially similar except for the influence of recency. Calkins (1986b) also attributed the modality effect to a storage rather than a retrieval process: "The suggestiveness, not the reproduction, seems to be increased in the auditory series" (p. 51). Negative Recency Effect When a recall test is delayed by a filled interval (test events, rehearsal-preventing activity), recall of terminal items in a sequence tends to fall below that of earlier items i n t t e sequence. This is especially true when a list is recalled immediately and then again some time later. In this case the effect of serial position is reversed: The last item in a list, typically recalled most frequently in an immediate test, is now least frequently recalled in the second, delayed test. This negative effect of recency (Craik, 1970) was described by Calkins in two ways. In her paired associate studies she compared the recall of pairs of a given kind that had been presented at different serial positions. She found that the last pair in a list was recalled less frequently than pairs from more remote serial positions when not tested immediately. She also advanced what would now be called an encoding or learning deficit interpretation of the effect: "This decrease is evidently the result of fatigue; the twelfth pair is not observed with the same attention as the earlier ones" (1894, p. 482). This, in fact, became a common interpretation of the effect much later (McCabe & Madigan, 1973). The occurrence of the negative recency effect in the serial position effects of an immediate and a delayed recall was also reported by Calkins in her replication of Kirkpatrick's (1894) study of free recall of objects and auditorially and visually presented object names (Calkins, 1898). Figure 1 shows Calkins's serial position data for immediate (I) and delayed (D) recall of a list of 10 auditorially presented words. The main point of these data 172 CD J-, -t-> a 40-CD •—• O S-, CD 20-- D 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Serial position 10 Note. Data are from "Short Studies in Memory and in Association From the Wellesley College Psychological Laboratory: I. A Study of Immediate and of Delayed Recall of the Concrete and of the Verbal" by M. W. Calkins, 1898, Psychological Review, 5, p. 453. for Calkins was that "in delayed recall of auditory words [the last item of a list] is even one of those least well remembered" (p. 456). The comparison of these results with an unwitting replication performed some 75 years later is interesting (Madigan, McCabe, & Itatani, 1972, Experiment 2). Figure 2 shows immediate serial recall and delayed free recall of lists of auditorially presented words from that study. Calkins's serial position effects are noisy (items were confounded with serial positions, and subjects were tested with only one list), but for all of the differences in design and procedure in the two experiments they both show the reversal of the effect of serial position in immediate and delayed tests. Primacy Effects Calkins (1986b) also noted important characteristics of primacy effects in immediate recall. These included the observation of "the ineffectiveness of primacy in the long series" (p. 46) and a cumulative rehearsal hypothesis about the origin of the effect: The subject "may not only accentuate the first presentation but recur to it while learning the rest of the series" (p. 46), a conclusion also reached by Glanzer (1972). Calkins may also have been the first to use the term primacy in connection with list recall experiments. February 1992 • American Psychologist Contingency Effects in Recall Figure 2 Serial Position Effects and the Negative Recency Effect in Immediate (I) and Delayed (D) Recall 100 Madigan et al. (1972) p I Although Calkins dealt with joint recall effects only briefly, her very thorough reporting of data allows readers to reconstruct 2 X 2 tables to examine contingency effects in recall. For example, given recall of the frequent pair, what was the probability of recall of a pairing presented once? Table 2 indicates a positive dependency in recall: Probability of recall of normal pairings was .220 (44/ 200) whereas probability of recall of normal pairings given recall of the frequent pairing was .308 (37/120). A similar analysis of vividness effects also indicates positive dependency in recall. The theoretical significance of analyses such as these was to be debated many years later (Hintzman, 1972). Afterwards 2 3 4 5 6 7 Serial position Note. Data are from "Immediate and Delayed Recall of Words and Pictures" by S. A. Madigan, L. McCabe, and S. Itatani, 1972, Canadian Journal of Psychology, 26, p. 411. Copyright 1972 by the Canadian Psychological AssociationAdapted by permission. Unlearning Effects As already noted, Calkins (1896b) used lists in which the same cue or stimulus item was paired with different response items. She described an effect obtained with such materials as "the negative result of habit, since the effect of habitual combination with a given stimulus is seen to be a small decrease in the likelihood of ordinary connection with the same stimulus" (p. 40). Table 2 illustrates the kind of data Calkins was considering. These data come from 200 test sequences in the visual presentation experiments, using lists in which there was a frequent pairing (e.g., violet-61 presented three times) and an "ordinary" pairing (e.g., violet-26 presented once). These data show an intraserial repetition effect, with items presented three times recalled with probability .60 (120/200). They also show an unlearning effect, with the ordinary pairing recalled with probability .22 (44/200). In this experiment the probability of recall of "normal" pairings (cue and response terms occurring once only, e.g., orange-84 in Table 1) was .26; the difference between this and the recall of ordinary pairings was what Calkins referred to as the negative result of habit. There are important differences between Calkins's procedures and the list-learning procedures usually used to study retroactive interference, but she was clearly describing interference effects in a way not very different from the unlearning account of retroactive interference (Barnes & Underwood, 1954). February 1992 • American Psychologist Calkins's theoretical and experimental efforts were met by an immediate disappointment. In 1895 she took the equivalent of a doctoral examination at Harvard University; the award of the doctoral degree was very enthusiastically recommended by James, Josiah Royce, and Miinsterburg, to no avail. Receipt of the recommendation was acknowledged but not acted on by Harvard. Calkins returned to Wellesley in 1895 as an associate professor and was appointed professor there in 1898, "the matter of her degree remaining unresolved" (Scarborough & Furumoto, 1987, p. 46). In 1902 she declined the offer of a doctorate from Radcliffe College. Twenty-five years later the issue was resolved, in a way: A petition to the university from Harvard degree holders to award Calkins the PhD was rejected. Calkins published no further along the lines of her 1894-1896 research, and her last publication on memory (Calkins, 1898) appears to have been the replication of Kirkpatrick's (1894) study. Her subsequent theoretical interests revolved around introspection and the concept oftheself(Hilgard, 1987). As Stevens and Gardner (1982) noted, Calkins was not mentioned by Boring (1929) in connection with the paired associate method and her name did not occur in the first comprehensive review of human learning (McGeoch, 1942). Her discoveries reviewed in this article appear to be essentially unknown and unacknowledged. Calkins's research is not entirely alone in this respect. A notable case is Daniels's (1893) research testing retention Table 2 Calkins's (1896) Unlearning and Dependency Effects in Recall with Frequent Pairings Ordinary pairing Frequent pairing Recalled Not recalled Total Recalled Not recalled Total 37 7 44 83 73 156 120 80 200 173 of a minimal amount of material over intervals up to 20 seconds with a distracting task—a procedure now known as the Brown-Peterson paradigm (Brown, 1958; Peterson & Peterson, 1959). Daniels's research has been cited only infrequently and sometimes misdated (Blumenthal, 1977; Murdock, 1987; Newman, 1987), and like Calkins' findings it did nothing to establish a continuing interest in phenomena of immediate memory. Accordingly, Calkins's and Daniels's research seem to fit Sarup's (1978) category of historical anticipations: "those antecedent ideas that have a likeness to, but not developmental ties with, later modes of thought" (p. 478). Calkins's and Daniels's studies are good examples of Newman's (1987) point that a wide variety of experimental methods were in use in memory research around the turn of the century; serial learning in the Ebbinghaus tradition was by no means the only procedure used. However, the study of multitrial learning and transfer that prevailed approximately between 1920 and 1960 proceeded without much attention to phenomena of immediate memory. More than 50 years would pass before they became the focus of intense experimental and theoretical efforts, and this perhaps explains the contemporary lack of awareness of earlier work such as Calkins's and Daniels's. It should also be said that Calkins herself downplayed the memory implications of her research: Her interest was in associative processes, and not in the use of the paired-associates procedure as a test of "mere memory" (1894, p. 479). She cited very little memory research of any kind in her 1894-1896 articles. Nonetheless, it should be clear from the examples of Calkins's methods, results, and writings that her work represents something more than old data that can be evaluated or reinterpreted in contemporary terms, and more than mere intimations of present-day theoretical concepts in earlier writings. Calkins explicitly recognized and vividly described several basic phenomena of immediate memory. A graph of serial position curves showing the effects of distracting activities on the recency effect has become almost as common in introductory texts as a graph of Ebbinghaus's curve of forgetting, and it seems appropriate that her discovery of this effect, among several others, be recognized as such. To quote one of the reviewers of this article, her writings on association and memory "constitute a truly remarkable legacy, as they represent important, basic, replicable phenomena that are fundamentally important to our current conceptualization of human memory." REFERENCES Barnes, J. M., & Underwood, B. J. (1954). "Fate" of first list associations in transfer theory. Journal of Experimental Psychology, 58, 97-105. Blumenthal, A. L. (1977). The process of cognition. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall. Boring, E. G. (1929). A history of experimental psychology. New York: Appleton. 174 Brown, J. (1958). Some tests of the decay theory of immediate memory. Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology, 10, 12-21. Calkins, M. W. (1894). Association: I. Psychological Review, I. 476483. Calkins, M. W. (1896a). Association: II. Psychological Review, 3, 3249. Calkins, M. W. (1896b). Association: An essay analytical and experimental. Psychological Review Monograph Supplements, 1, (2). Calkins, M. W. (1898). Short studies in memory and in association from the Wellesley College Psychological Laboratory: I. A study of immediate and of delayed recall of the concrete and of the verbal. Psychological Review, 5, 451-456. Calkins, M. W. (1930). Mary Whiton Calkins. In C. Murchison, (Ed.) A history of psychology in autobiography (Vol. 1, pp. 31 -62), Worcester, MA: Clark University Press. Cofer, C. (1979). Human learning and memory. In I. E. Hearst (Ed.), The first century of experimental psychology (pp. 323-370). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum. Craik, F. I. M. (1970). The fate of primary memory items in free recall. Journal of Verbal Learning and Verbal Behavior, 9, 143-148. Daniels, A. H. (1893). The memory after-image and attention. The American Journal of Psychology, 6, 558-564. Furumoto, L. (1979). Mary Whiton Calkins (1863-1930): Fourteenth president of the American Psychological Association. Journal of the History of the Behavioral Sciences, 15, 346-356. Glanzer, M. (1972). Storage mechanisms in free recall. In G. H. Bower (Ed.), The psychology of learning and motivation: Advances in research and theory (Vol. 5, pp. 129-193). San Diego, CA: Academic Press. Hilgard, E. (1987). Psychology in America: A historical survey. San Diego, CA: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich. Hintzman, D. L. (1972). On testing the independence of associations. Psychological Review, 79, 261-264. Kirkpatrick, E. A. (1894). An experimental study of memory. Psychological Review, 1, 602-609. Madigan, S. A., McCabe, L., & Itatani, S. (1972). Immediate and delayed recall of words and pictures. Canadian Journal of Psychology, 26, 407-414. McCabe, L., & Madigan, S. (1973). Negative effects of recency in recall and recognition. Journal of Verbal Learning and Verbal Behavior, 10, 307-310. McGeoch, J. (1942). The psychology of human learning. New York: Longmans, Green. Murdock, B. B., Jr. (1974). Human memory: Theory and data. New York: Wiley. Murdock, B. B., Jr. (1987). Serial order effects in a distributed memory model. In D. S. Gorfein & R. R. Hoffman (Eds.), Memory and learning: The Ebbinghaus centennial conference (pp. 277-331). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum. Newman, S. E. (1987). Ebbinghaus' "On Memory": Some effects on early American research. In D. S. Gorfein & R. R. Hoffman (Eds.), Memory and learning: The Ebbinghaus centennial conference (pp. 77-87). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum. Peterson, L. R., & Peterson, M. J. (1959). Short-term retention of individual verbal items. Journal of Experimental Psychology, 58, 193— 198. Postman, L. (1985). Human learning. In G. A. Kimble & K. Schlesinger (Eds.), Topics in the history of psychology (Vol. 1, pp. 69-133). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum. Sarup, G. (1978). Historical antecedents of psychology: The recurrent issue of old wine in new bottles. A merican Psychologist, 33, 478-485. Scarborough, E., & Furumoto, L. (1987). Untold lives: The first generation of American women psychologists. New York: Columbia University Press. Stevens, G., & Gardner, S. (1982). The women ofpsychology. Cambridge, MA: Schenkman. Thorndike, E. L. (1908). Memory for paired associates. Psychological Review, 15, 122-138. February 1992 • American Psychologist