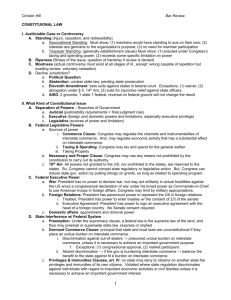

Constitutional Law - February 2010

advertisement

QUESTION NO. 7 FEBRUARY 2010 OREGON BAR EXAM The State of Franklin is in the midst of a deep economic recession. Unemployment is high. Franklin’s tax revenues are down and government services are being cut. Two important industries in Franklin are food processing and micro-brewed beer. In response to the economic crisis, the Franklin Legislature enacted a package of three bills: House Bill 25 requires that crops grown in Franklin be processed or packaged at food processing plants in Franklin before sale or export. House Bill 50 provides that any U.S. citizen paying Franklin state income tax is entitled to a deduction for childcare expenditures incurred while seeking employment. House Bill 100 imposes a 5% tax on beer imported from foreign countries. You are legal counsel to the Governor of Franklin. The Governor has asked you if any of these bills likely violate any provision of the U.S. Constitution. The Governor will veto a bill if you advise her that the bill is most likely unconstitutional. Discuss potential arguments and counterarguments that might be raised regarding the validity of each bill under the U.S. Constitution and whether you would advise the Governor to sign or veto: (35%) 1. House Bill 25. (35%) 2. House Bill 50. (30%) 3. House Bill 100. © 2010 Oregon State Board of Bar Examiners QUESTION NO. 7 FEBRUARY 2010 OREGON BAR EXAM Constitutional Law Answer Outline I. House Bill 25 requires that crops grown in Franklin be processed or packaged at food processing plants in Franklin before sale or export. ISSUE: Dormant Commerce Clause a. Unless preempted by Congress, state governments generally may regulate local aspects of interstate commerce as long as the regulation: i. Does not discriminate against out-of-state competition to benefit local economic interests; and ii. Is not unduly burdensome (the incidental burden on interstate commerce does not outweigh the legitimate local benefit of the regulation). If a state regulation is discriminatory, it will generally be upheld only if the regulation furthers an important state interest and there are no reasonable non-discriminatory alternatives, or if the state is a market participant. b. State regulations that discriminate against interstate commerce that operate in the nature of a tariff or trade barrier against out-of-state competitors are almost always invalid. The Supreme Court has sometimes said that such regulations are subject to “rigorous scrutiny.” i. See, e.g., C & A Carbone, Inc. v. Town of Clarkstown, N.Y., 511 U.S. 383, 392 (1994): “Discrimination against interstate commerce in favor of local business or investment is per se invalid, save in a narrow class of cases in which the municipality can demonstrate, under rigorous scrutiny, that it has no other means to advance a legitimate local interest.” 1. In Carbone, a local ordinance that required all local solid waste to be processed at the local waste processing plant was held to be a violation of the dormant commerce clause. The town had enacted the ordinance in order to finance the construction of the plant. 2. Although the regulation only applied to the local transport of waste, its effects were interstate in reach. 3. The regulation deprived competitors, including out-ofstate firms, access to the local market. c. Such regulations have long been held invalid. As summarized by the Court in Carbone: “In Dean Milk Co. v. Madison, 340 U.S. 349, 71 S.Ct. 295, 95 L.Ed. 329 (1951), we struck down a city ordinance that required all milk sold in the city to be pasteurized within five miles of the city lines. We found it “immaterial that Wisconsin milk from outside the Madison area is subjected to the same proscription as that moving in interstate commerce.” * * * In this light, the flow control ordinance is just one more instance of local processing requirements that we long have held invalid. See Minnesota v. Barber, 136 U.S. 313, 10 S.Ct. 862, 34 L.Ed. 455 (1890) (striking down a Minnesota statute that required any meat sold within the State, whether originating within or without the State, to be examined by an inspector within the State); FosterFountain Packing Co. v. Haydel, 278 U.S. 1, 49 S.Ct. 1, 73 L.Ed. 147 (1928) (striking down a Louisiana statute that forbade shrimp to be exported unless the heads and hulls had first been removed within the State); Johnson v. Haydel, 278 U.S. 16, 49 S.Ct. 6, 73 L.Ed. 155 (1928) (striking down analogous Louisiana statute for oysters); Toomer v. Witsell, 334 U.S. 385, 68 S.Ct. 1156, 92 L.Ed. 1460 (1948) (striking down South Carolina statute that required shrimp fishermen to unload, pack, and stamp their catch before shipping it to another State); Pike v. Bruce Church, Inc., supra (striking down Arizona statute that required all Arizona-grown cantaloupes to be packaged within the State prior to export); South-Central Timber Development, Inc. v. Wunnicke, 467 U.S. 82, 104 S.Ct. 2237, 81 L.Ed.2d 71 (1984) (striking down an Alaska regulation that required all Alaska timber to be processed within the State prior to export). The essential vice in laws of this sort is that they bar the import of the processing service. Outof-state meat inspectors, or shrimp hullers, or milk pasteurizers, are deprived of access to local demand for their services. Put another way, the offending local laws hoard a local resource-be it meat, shrimp, or milk-for the benefit of local businesses that treat it.” Id. 391-2. d. House Bill 25 is a local processing requirement of just this sort. The bill would discriminate against interstate commerce by barring outof-state food processors from the market of processing crops grown in Franklin. It is not likely that Franklin can demonstrate, under rigorous scrutiny, that House Bill 25 is the only means available to advance a legitimate local interest. In fact, it is not clear that Franklin could demonstrate any legitimate local interest being advanced. e. House Bill 25 is most likely unconstitutional and should be vetoed. II. House Bill 50 provides a state income tax deduction to any United States citizen residing in Franklin for child care expenditures incurred while seeking employment. ISSUES: 14th Amendment Equal Protection (Alienage Discrimination) and Congress’ Art. I, Sec. 4 “naturalization” power a. The 14th Amendment applies to actions of state governments. State government classification of people is subject to one of three levels of scrutiny: i. Strict scrutiny applies if the classification is a “suspect classification” or involves a “fundamental right.” State government classifications based on race, national origin, and alienage are suspect classifications. To survive strict scrutiny, such classification must be necessary to achieve a compelling government interest. ii. Intermediate scrutiny applies if the classification is a “quasisuspect classification.” Classifications based on gender or legitimacy are treated as quasi-suspect classifications. To survive intermediate scrutiny, such classification must be substantially related to an important government interest. iii. Rational basis review applies to any other classification. To survive rational basis review, the classification must be rationally related to a legitimate government interest. b. State law classifications based on alienage, such as laws that condition benefits on citizenship, are usually subject to strict scrutiny (with at least one exception), and are generally invalid. i. For instance, in Graham v. Richardson, 403 U.S. 365 (1971), the Court held invalid a state statute that denied welfare benefits to resident aliens and one that denied them to aliens who had not resided in the United States for a specified number of years. ii. In applying strict scrutiny, the Graham Court stated: “a State's desire to preserve limited welfare benefits for its own citizens is inadequate to justify Pennsylvania's making noncitizens ineligible for public assistance, and Arizona's restricting benefits to citizens and longtime resident aliens. * * * [T]he ‘justification of limiting expenses is particularly inappropriate and unreasonable when the discriminated class consists of aliens. Aliens like citizens pay taxes and may be called into the armed forces. * * * [A]liens may live within a state for many years, work in the state and contribute to the economic growth of the state.’ * * * There can be no ‘special public interest’ in tax revenues to which aliens have contributed on an equal basis with the residents of the State.” Id. at 375-6. iii. Similarly, the Court has invalidated state laws requiring U.S. citizenship in order to be admitted to the bar, Application of Griffiths, 413 U.S. 717 (1973), or to compete for civil service jobs, Sugarman v. Dougall, 413 U.S. 634 (1973). However, the Court has exempted from strict scrutiny those state government classifications requiring U.S. citizenship that “are bound up with the operation of the state as a governmental entity.” Ambach v. Norwick, 441 U.S. 69 (1979). Therefore, citizenship requirements for employment as a teacher, id., and police officer, Foley v. Connelie, 435 U.S. 291 (1978), have been subject only to rational basis review and upheld. This exception is referred to as the Self Governance or Political Function exception to strict scrutiny. c. House Bill 50 explicitly makes a government benefit (i.e., a tax deduction) contingent on U.S. citizenship. It is unlikely that Franklin can demonstrate that such a classification is necessary to achieve a compelling government interest. Preserving limited state resources for the benefit of citizens has been held to not be a compelling government interest. d. An additional argument against the validity of House Bill 50 is that it infringes upon Congress’s authority under Article I, Section 4 to “establish a uniform rule of naturalization.” In Graham, the Court held that state restrictions on state benefits were also contrary to Art. I, Sec. 4 because “State laws that restrict the eligibility of aliens for welfare benefits merely because of their alienage conflict with * * * overriding national policies in an area constitutionally entrusted to the Federal Government.” Graham, at 378. Therefore, unless Congress has authorized such a distinction based on citizenship, states may not infringe on Congress’ plenary authority over citizenship issues by enacting laws making state benefits contingent on citizenship. e. House Bill 50 is most likely unconstitutional and should be vetoed. III. House Bill 100 imposes a 5% tax on beer imported from a foreign country. ISSUES: Import-Export Clause, Commerce Clause and 21st Amendment a. Article I, Section 10 states that “No state shall, without the Consent of Congress, lay any Imposts or Duties on Imports or Exports, except what may be absolutely necessary for executing its inspections Laws . . .” b. This tax on beer, which applies only to beer imported from a foreign country and not to beer made in Franklin or elsewhere in the U.S., is most likely a state duty on an import and therefore contrary to Art. I, Sec. 10. c. In addition, the Commerce Clause gives Congress the exclusive authority to regulate foreign (as well as interstate) commerce. i. See I.a above for general Commerce Clause discrimination test. ii. In addition, in cases involving foreign commerce, a state tax is also invalidated if it would create a substantial risk of international multiple taxation or would prevent the federal government from “speaking with one voice” regarding international trade or foreign affairs issues. Barclays Bank PLC v. Franchise Tax Board, 512 U.S. 298 (1994). d. This tax is discriminatory since it applies only to beer imported from foreign countries. It is unlikely that Franklin could argue that such a tax furthers an important state interest and that there are no reasonable nondiscriminatory alternatives. e. Franklin might argue that it has broad latitude under the 21st Amendment to regulate and tax alcoholic beverages and that such power supersedes Commerce Clause and Import-Export Clause limitations. However, in a case where the state regulation appears so clearly to be an exercise of economic favoritism for local business, such argument is likely to fail. i. The 21st Amendment repealed Prohibition in 1933. Sec. 2 of the Amendment provides that “The transportation or importation into any State . . . for delivery or use therein of intoxicating liquors, in violation of the laws thereof, is hereby prohibited.” ii. In Granholm v. Heald, 544 U.S. 460 (2005), the Supreme Court confirmed that “the 21st Amendment does not supersede other provisions in the Constitution and, in particular, does not displace the rule that States may not give a discriminatory preference to their own producers.” f. House Bill 100 is most likely unconstitutional and should be vetoed. © 2010 Oregon State Board of Bar Examiners