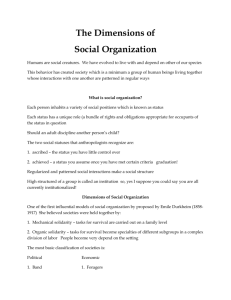

Social Effects of Industrialization

advertisement

August 11,1956 THE ECONOMIC WEEKLY Social Effects of Industrialization Walter C Neale IN discussions of economic g r o w t h perhaps most a t t e n t i o n is paid to measurable quantities, a n d the problem, quite r i g h t l y , is treated as one of creating more of the m a t e r i a l means of s a t i s f y i n g h u m a n w a n t s . The great a i m of programmes of i n d u s t r i a l development is to provide more and more of the goods a n d the good things of l i f e . W h i l e this a i m is quite proper, in f a c t essential to n a t i o n a l well-being and social s t a b i l i t y in the modern w o r l d , the process of i n d u s t r i a l i z a t i o n has side-effects, by-products w h i c h change the whole tenor o f life a n d t h o u g h t . I n d u s t r i a l society is I n e v i t a b l y different f r o m p r e - i n d u s t r i a l society, and the differences are not merely differences in the quantities a n d kinds of goods a n d services available. The citizens of an industrialized community w i l l have different values, different ways of thought, and different ways of l i v i n g their everyday lives. Generally, these non-economic effects of development cannot be measured in a m e a n i n g f u l way, a l t h o u g h it is possible t h a t some aspects or frends can be measured, such as the number of people in a new social class, the disappearance of an old group in the society, or the number of people l i v i n g permanently in an area other t h a n the area in w h i c h they were born. It is not possible, however, to a t t a c h quantities to new modes of thought, or new attitudes t o w a r d the f a m i l y , yet such changes are of the greatest importance to the people i n v o l v e d and can give in the w e s t have given—rise to tensions and conflict. Often Regretted These changes in the ways of life a n d t h o u g h t are often unforeseen a n d as often regretted. People w h o were b o r n and bred in a different atmosphere w i l l never be completely happy In a changed society, a n d there is m u c h h a r k i n g back t o the ' g o o d old days". I n its extreme f o r m this h a r k i n g back takes the f o r m o f r o m a n t i c i z i n g the past u n t i l the, rea c t i o n a r y picture of the "good old days'' w o u l d never be recognized by those w h o l i v e d t h e m , A danger to, a n d a measure of the success of, p l a n n e d i n d u s t r i a l development is the society's a b i l i t y to adjust to a n d accept the q u a l i t a t i v e changes w h i c h f o l l o w it the w a k e of a new economic system and to relieve and control the tensions and conflicts w h i c h arise because of these changes. The w o r l d ' s experience of indust r i a l i z a t i o n has been r a t h e r l i m i t e d , and so one hesitates to read the past of C h r i s t i a n Europe i n t o the future of civilizations resting upon a v e r y different past. There are enough differences between the societies of the U n i t e d States, Great B r i t a i n , and Germany to w a r n us t h a t an industrialized I n d i a w i l l look very different from an industrialized B r i t a i n . However, despite our expectation t h a t the process of industrialization w i l l affect different societies differently, one can perceive in the process certain essential elements w h i c h must have s i m i l a r effects, no m a t t e r w h a t the social context in w h i c h they operate. Way of Thinking These common effects w i l l stem f r o m the scientific a n d mechanistic character of i n d u s t r i a l operations, f r o m the technical requirements of o r g a n i z a t i o n a l techniques used to keep an i n d u s t r i a l society r u n n i n g . L e t us t a k e first, the effect, of i n d u s t r i a l development on the w a y of t h i n k i n g . The i n d u s t r i a l process is mechanical, and the t h i n k i n g needed to set up and manage a f a c t o r y is scientific. It has been said t h a t the man who works in an industrial establishment lives in a " w o r l d of m a t t e r - o f - f a c t " or of cause and effect. H i s daily a c t i v i t y , whether on a f a i r l y simple level of m a n u a l operations or on a much higher level of design and organization, puts h i m face to face at a l l times w i t h the results of his actions. Frequently a l m o s t no time elapses between the t a k i n g of an action and the result. Even w h e n the t i m e lapse is appreciable, there are not l i k e l y to be m a n y extraneous circumstances i n t e r r u p t i n g the process. This constant rea l i z a t i o n t h a t certain actions lead i n e v i t a b l y to particular results, a n d that particular results cannot be achieved except by specific actions creates a habit of t h o u g h t w h i c h can be called scientific, mechanistic, or matter-of-fact, a n d this h a b i t o f t h o u g h t is n a t u r a l l y c a r r i e d over toother spheres of l i f e . In fact, the m a n w h o has r u n a die press or set up a production line w i l l never t h i n k in the same m a n n e r a g a i n . T h e p o i n t can be made by compari n g the i n d u s t r i a l process w i t h the k i n d of life led by men engaged in a g r i c u l t u r a l pursuits. Whereas the cycle of events in a f a c t o r y m a y t a k e only moments, the cycle of events in the countryside takes at least a season, and in some respects extends over the years. In the f a c t o r y m o s t elements of the productive process are directly under the c o n t r o l of t h e people w o r k i n g in the factory. In f a r m i n g very few of the processed are completely controlled by the f a r mer. The g r o w t h of plants is a b o t anical m a t t e r . The f a r m e r can help nature along, b u t m u c h of the burden is hers, n o t his. F u r t h e r m o r e , m a n y events can intervene to upset expectations. I n I n d i a the q u a n t i t y a n d t i m i n g of r a i n f a l l is extremely important. Other elements, such as the f e r t i l i t y of the soil, are p a r t l y under' the c o n t r o l of the farmer, but the period over w h i c h f e r t i l i t y deteriorates m a y be so l o n g t h a t cause a n a effect are never b r o u g h t home to the farmer. It is easy to understand w h y the i n d u s t r i a l m a n says t h a t "this causes t h a t " while the f a r m e r regards events as the w i l l of God. Industrial Worker Vs Rural Craftsman One m a y ask w h y the attitude of the i n d u s t r i a l w o r k e r is not also the a t t i t u d e of the r u r a l craftsman, a n d to an extent they no doubt have something in common. The craftsm a n k n o w s his m a t e r i a l s a n d cont r o l s them directly, so t h a t he k n o w s whem he starts the product w h i c h he w i l l have when he is finished. Nevertheless, it remains true t h a t the c r a f t s m a n is n o t made so f u l l y conscious of the cause a n d effect character o f his w o r k . The craftsman goes t h r o u g h a series of operations w h i c h could m a k e h i m look at the w o r l d as a l l cause a n d effect b u t for t w o facets of his l i f e . On the one h a n d he lives a m o n g a vast m a j o r i t y w h i c h do n o t have the i m m e d i a t e m a t t e r - o f - f a c t experience of controlled p r o d u c t i o n — a n d neighbour's thoughts are our thoughts, and on the other h a n d his c r a f t is apt to be t r a d i t i o n a l a n d h i g h l y stable. This s t a b i l i t y means t h a t he does n o t have to w o r r y about w h a t he does; he k n o w s a l l about it to begin w i t h . But the i n d u s t r i a l w o r k e r is constant* ly seeing changes in the productive process t a k i n g place. T h i s used to be done w i t h such-and-such results. N o w a new process is introduced, a n d August 11,1956 THE ECONOMIC WEEKLY THE ECONOMIC WEEKLY August 11, 1956 the results are somewhat different, or he is called upon to do a somew h a t different j o b . I n consequence he is made aware t h a t the w o r l d - o f m a t t e r - o f - f a c t can be changed a n d directed. Of course, if he is a technologist m u c h of, his effort is devoted to j u s t this problem of scientific c o n t r o l a n d change. Matter-of-fact Attitude I n p r e - i n d u s t r i a l society the dom i n a n t mode of t h o u g h t is t h a t of the a g r i c u l t u r i s t a w o r l d in w h i c h prayer m a y seem as efficacious as fencing, and' in some years more efficacious, in w h i c h the cycle of the seasons a n d the mysteries of nature are a l w a y s before h i m . I n i n d u s t r i a l society the d o m i n a n t mode of t h o u g h t is t h a t of the technologist—a w o r l d in w h i c h prayer is obviously less effective t h a n l u b r i c a t i o n and tensile s t r e n g t h ; in which each day is m u c h l i k e any other and in w h i c h there are far fewer mysteries and he k n o w s how to manage them. N o w , this mode of matter-of-fact t h o u g h t carries over into the rest of the industrial workers life. He is apt to become un-religious. By this I do not mean that he becomes irreligious. Rather he no longer regards religious observances as i m p o r t a n t in m a n y of the t h i n g s he undertakes. He develops in the social sphere attitudes of doubt and i n q u i r y which are satisfied only by a mechanistic answer. As he shapes a. p a r t w i t h his machine, so he begins to feel t h a t he can shape bis life. As he asks " w h y " about the amount of power used for an indust r i a l operation, so he asks w h y about the rest of his l i f e : w h y should he support his ne'er-do-well brother, or w h y should he not smoke. A n s w e r s l i k e d u t y and m o r a l o b l i g a t i o n c a r r y less weight, unless he can be shown t h a t there is a p r a c t i c a l advantage, or t h a t his acts of omission or commission w i l l have effects he does not w a n t . A n d the breakdown of the old standards comes w h e n he says to himself t h a t he doesn't care about t h a t brother, a n d doesn't in the least m i n d the results of his o w n w i t h h o l d i n g of help. t r i a l establishments t o f i n d the r i g h t t h e m a r g i n between efficiency a n d is and the extra m a n f o r the j o b regardless o f h i sefficiency of maintaining traditional status i n society. I n I n d i a today cost there is s t i l l a strong tendency to standards does n o t seem w o r t h w h i l e . hire a m a n of ones o w n f a m i l y or The i n d u s t r i a l m a n a g e r w h o w a n t s caste, a n d one would h a r d l y expect to hire only members of his o w n community m a y find t h a t there are not the t r a d i t i o n a l values to b r e a k d o w n a n d disappear as soon as factories enough of them to m a n his p l a n t , a n d are erected. However, there m u s t be so perforce the old values pass. Once constant pressure on managers to the break is made it becomes difficult pass over brothers-in-law w h o k n o w to re-establish the old f o r m s . n o t h i n g o f the technology i n f a v o u r Demarcation Blurred of strangers w h o r a n get the j o b done In a f a i r l y stable society clear properly, a n d one expects t h a t these lines of demarcation can be d r a w n pressures w i l l become m o r e acute as between various functions, a n d these the need f o r technical competence befunctions assigned to specific social comes increasingly clear. groups. In i n d u s t r i a l society the The size and complexity of f a c t o r y lines are not so clear; the content of establishments also tend to break jobs fluctuates; new functions arise down the lines of f a m i l y a n d caste. unci o l d ones disappear. If the proW h e n o n l y a few people are needed, cess takes l o n g enough the class it is a f a i r l y simple m a t t e r to keep structure can adapt, but it is comthe establishment in the hands of the m o n l y the case in an i n d u s t r i a l so"in-group", b u t when hundreds are ciety t h a t the changes take place too needed it becomes increasingly diffi- r a p i d l y to a l l o w for such adjustment. cult. I n i n d u s t r i a l establishments Locomotive firemen are displaced by diesels; airline hostesses a n d chemical engineers suddenly arise; a decade or t w o can eliminate the w h e e l w r i g h t . J u r i s d i c t i o n a l disputes a m o n g unions in the west, m a y be in p a r t efforts to m a i n t a i n s t a b i l i t y in the s t r u c t u r e ol the w o r k force ("they are c e r t a i n l y efforts to gain monopoly r e t u r n s ) , but. no union has m a i n t a i n e d its character against changes in productive techniques. Perhaps the most i m p o r t a n t organizational technique, so far as this discussion is concerned, is the payment of wages. Regular payment of wages in cash can be expected to have definite effects in b r e a k i n g down the t r a d i t i o n a l f a m i l y structure. I t is not t h a t twelve chips a week makes a m a n more selfish, or causes h i m to love his m o t h e r less. Rather, it is that it gives h i m new o p p o r t u n i ties to be independent. In a closely k n i t a g r i c u l t u r a l society the son is dependent upon the father, the brothers upon each other. The w o m e n of the f a m i l y have no means of supp o r t except in the cooperative venture of the f a m i l y . But wages end these dependencies. The son is as capable of e a r n i n g a l i v i n g as the father; the sister as the brother. An u n m a r r i e d or childless w o m a n can leave home to w o r k if she doesn't like the home atmosphere. The obverse of the coin is t h a t the f a m i l y dependent upon earnings in i n d u s t r y is no more secure t h a n its i n d i v i d u a l members. On an a g r i c u l t u r a l h o l d i n g there is, b a r r i n g disasters, always w o r k a n d food f o r the f a m i l y , but i f f a t h e r loses his j o b at the m i l l , the f a m i l y ' s Class and family Structure The technical requirements of i n d u s t r y also affect the class a n d f a m i l y structure of a p r e - i n d u s t r i a l society. I n each b r a n c h a n d i n each Job i n d u s t r y requires technical competence. There is no substitute f o r k n o w i n g h o w to do y o u r Job w e l l . T h i s means t h a t there i s constant pressure on the managers of indus953 August 11, 1956 THE ECONOMIC WEEKLY means of support is gone a n d the. f a m i l y w i l l very l i k e l y look w i t h f a v o u r on those of its members w h o decide to move out. and off. Greater Mobility An i n d u s t r i a l .society requires greater m o b i l i t y , b o t h occupational and .spatial. As people m o v e up ana down a n d across the frame of occupations and .skills, t h e lines dem a r c a t i n g caste or c o m m u n i t y begin to go. It becomes h a r d e r and barder to keep t r a c k of a man's social position. F u r t h e r m o r e , the social position begins to correspond less and less w i t h a man's income and his i m portance in the economy. As incomes a n d economic status become scrambled, it becomes increasingly difficult to t a k e seriously the ancestral posit i o n of the citizens of the i n d u s t r i a l world. W h e n movement f r o m place to place is slow or infrequent, the society can keep t r a c k of each person's t r a d i t i o n a l position, bid when movem e n t is r a p i d and widespread the fine g r a d a t i o n s tend to disappear. In I n d i a today in the large cities the caste postion of each person is s t i l l definitely recognized, but I have the definite impression that the caste blocks in the cities are far larger a n d more inclusive than they are in the villages, a n d the importance of sub-castes m u c h less. In addition, the castes are to a large extent local. The process of i n d u s t r i a l i z a t i o n j u m bles castes f r o m different, localities together' .so that it is not easy to establish the essential hierarchy a m o n g t h e m . W h e n it is impossible to establish the h i e r a r c h i c a l r e l a t i o n ships a m o n g the castes one of their m a j o r functions in o r g a n i z i n g the social relationships between people ceases, and there is t h a t m u c h less purpose in m a i n t a i n i n g the distinctions. Smaller Family Unit It can also be. seen t h a t movement about the c o u n t r y w i l l tend to break d o w n the larger f a m i l y units. W i t h each m a n l i v i n g in a different locality a n d receiving his own pay packet, t h e n a t u r a l unit becomes the biological f a m i l y of man. woman, and m i n o r c h i l d r e n . By no means does t h i s i m p l y t h a t that there w i l l be any lessening of the bonds of love bet w e e n parents and chuden and b r o t h e r s a n d sisters (perhaps it w i l l be easier to love, domestic tensions being less), nor t h a t mutual support and aid will die out. W h e n I say t h a t it is l i k e l y t h a t the l a r g e r f a m i l y w i l l break down, I mean that w i t h separate means o f m a i n t e n a n c e a n d separate households the d a i l y a n d i n fact most of the m a j o r decisions w i l l come to be taken in the smaller households of m a n and w i f e . Certainly today one can see this happening in the cities a m o n g professional and business people whose parents' and g r a n d parents' families were not so broken up i n t o smaller units. The policy of the Government of India is to e l i m i n a t e the differentials based upon h e r e d i t a r y caste, so t h a t it is encouraging to feel t h a t the movement towards an i n d u s t r i a l society w i l l of its own accord move in step w i t h the policy of the g o v e r n ment. It is not so clear chat the other effects of i n d u s t r i a l i z a t i o n upon the attitudes! and ways of l i v i n g w i l l be so widely welcomed. B u t changes of the kinds o u t l i n e d above seem l i k e l y to occur simply as a result of the creation of an i n d u s t r i a l society.