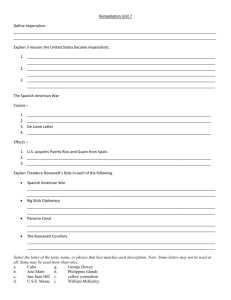

I need a hero: a study of the power of the myth and yellow journalism

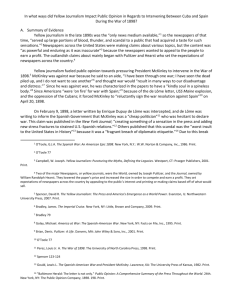

advertisement