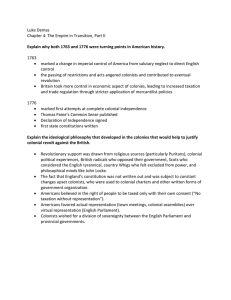

Document

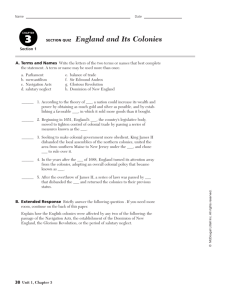

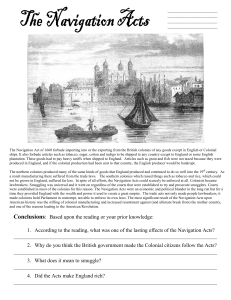

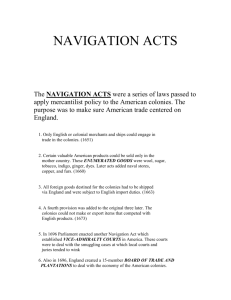

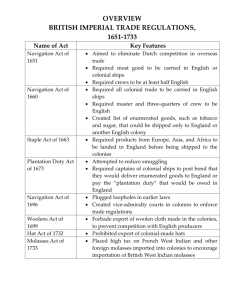

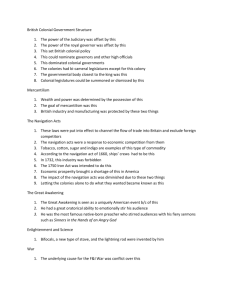

advertisement

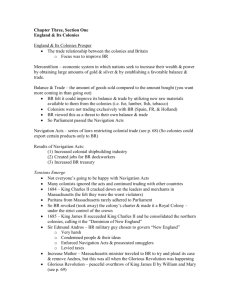

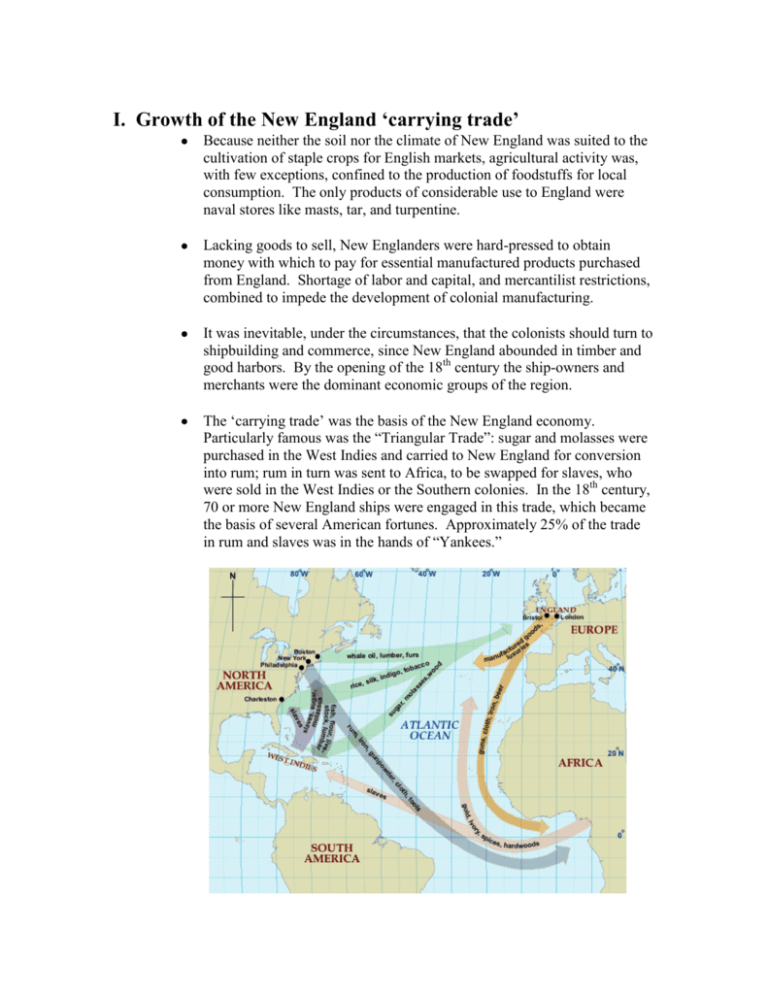

I. Growth of the New England „carrying trade‟ Because neither the soil nor the climate of New England was suited to the cultivation of staple crops for English markets, agricultural activity was, with few exceptions, confined to the production of foodstuffs for local consumption. The only products of considerable use to England were naval stores like masts, tar, and turpentine. Lacking goods to sell, New Englanders were hard-pressed to obtain money with which to pay for essential manufactured products purchased from England. Shortage of labor and capital, and mercantilist restrictions, combined to impede the development of colonial manufacturing. It was inevitable, under the circumstances, that the colonists should turn to shipbuilding and commerce, since New England abounded in timber and good harbors. By the opening of the 18th century the ship-owners and merchants were the dominant economic groups of the region. The „carrying trade‟ was the basis of the New England economy. Particularly famous was the “Triangular Trade”: sugar and molasses were purchased in the West Indies and carried to New England for conversion into rum; rum in turn was sent to Africa, to be swapped for slaves, who were sold in the West Indies or the Southern colonies. In the 18th century, 70 or more New England ships were engaged in this trade, which became the basis of several American fortunes. Approximately 25% of the trade in rum and slaves was in the hands of “Yankees.” Traces of the Trade II. The Navigation Acts To protect the mercantile system, England passed a series of laws called Navigation Acts, starting in 1651. Colonies were required to sell certain items (“enumerated goods”) only to England or other colonies. Trade between England and the colonies had to be on English ships (built in England or the colonies). It is understandable that the commercial men of New England found the British trade regulations onerous. They would have been glad to engage in direct trade with Europe, avoiding the „enumerated articles‟ laws—and a substantial number did so. From the time of their enactment until the French and Indian War, the Navigation Acts were flouted with considerable success; smuggling was so widespread as to become respectable! English merchants, whom the laws were designed to protect, were annoyed at the violations, which sometimes enabled colonial traders to undersell them in European and colonial markets. Their demands were persistent, but until after the middle of the 18th century, the Privy Council made only sporadic efforts to tighten up law enforcement. III. Reasons for Nonenforcement of the Laws (“Salutary Neglect”) For almost a century the English were too busy with the internal readjustments which attended the Glorious Revolution of 1688 and with their long imperial rivalry with France to give full attention to colonial problems; furthermore, as long as the French menace remained, it was inadvisable to risk alienating the colonists by drastic action. During the years of “salutary neglect”, none of the principles of mercantilist legislation was abandoned, but the application of them was relaxed. When at last the French were banished from the North American mainland in 1763 and the British were in a position to act against New England law violations, the colonists had grown so accustomed to their comparative freedom that they reacted violently. It is not surprising that New England, the „square peg‟ in the British colonial structure, was the scene of the most explosive incidents of the pre-Revolutionary years.