Informational Text Structure

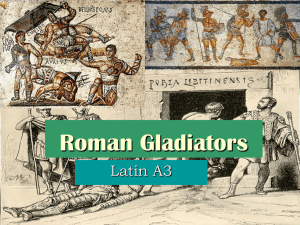

advertisement

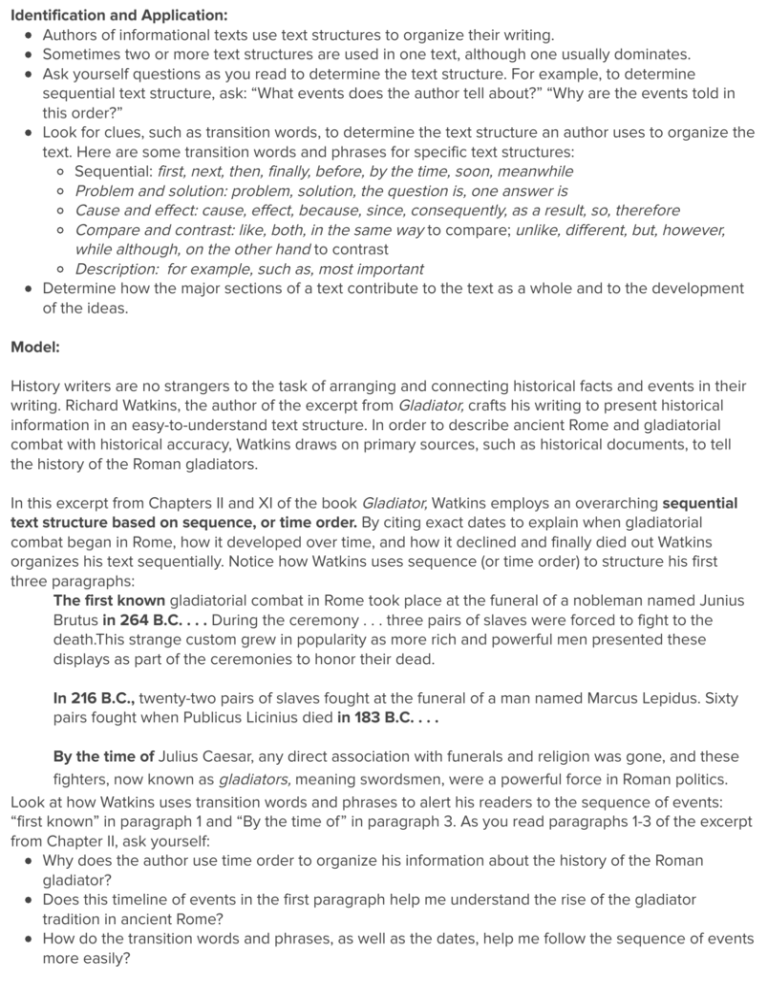

Identification and Application: Authors of informational texts use text structures to organize their writing. Sometimes two or more text structures are used in one text, although one usually dominates. Ask yourself questions as you read to determine the text structure. For example, to determine sequential text structure, ask: “What events does the author tell about?” “Why are the events told in this order?” Look for clues, such as transition words, to determine the text structure an author uses to organize the text. Here are some transition words and phrases for specific text structures: Sequential: first, next, then, finally, before, by the time, soon, meanwhile Problem and solution: problem, solution, the question is, one answer is Cause and effect: cause, effect, because, since, consequently, as a result, so, therefore Compare and contrast: like, both, in the same way to compare; unlike, different, but, however, while although, on the other hand to contrast Description: for example, such as, most important Determine how the major sections of a text contribute to the text as a whole and to the development of the ideas. Model: History writers are no strangers to the task of arranging and connecting historical facts and events in their writing. Richard Watkins, the author of the excerpt from Gladiator, crafts his writing to present historical information in an easy-to-understand text structure. In order to describe ancient Rome and gladiatorial combat with historical accuracy, Watkins draws on primary sources, such as historical documents, to tell the history of the Roman gladiators. In this excerpt from Chapters II and XI of the book Gladiator, Watkins employs an overarching sequential text structure based on sequence, or time order. By citing exact dates to explain when gladiatorial combat began in Rome, how it developed over time, and how it declined and finally died out Watkins organizes his text sequentially. Notice how Watkins uses sequence (or time order) to structure his first three paragraphs: The first known gladiatorial combat in Rome took place at the funeral of a nobleman named Junius Brutus in 264 B.C. . . . During the ceremony . . . three pairs of slaves were forced to fight to the death.This strange custom grew in popularity as more rich and powerful men presented these displays as part of the ceremonies to honor their dead. In 216 B.C., twenty-two pairs of slaves fought at the funeral of a man named Marcus Lepidus. Sixty pairs fought when Publicus Licinius died in 183 B.C. . . . By the time of Julius Caesar, any direct association with funerals and religion was gone, and these fighters, now known as gladiators, meaning swordsmen, were a powerful force in Roman politics. Look at how Watkins uses transition words and phrases to alert his readers to the sequence of events: “first known” in paragraph 1 and “By the time of” in paragraph 3. As you read paragraphs 1-3 of the excerpt from Chapter II, ask yourself: Why does the author use time order to organize his information about the history of the Roman gladiator? Does this timeline of events in the first paragraph help me understand the rise of the gladiator tradition in ancient Rome? How do the transition words and phrases, as well as the dates, help me follow the sequence of events more easily? Within this overarching sequential text structure, Watkins uses a cause-and-effect text structure to tell how or why events occurred (the cause) and what happened as a result (the effect). Pay close attention to sentences 1 and 6 in the fourth paragraph of Chapter XI: It took the rise of a new faith to change the attitudes of ruler and ruled alike enough to stop gladiatorial combat. Christianity was born in the Roman Empire and found many converts among the poor and powerless. The pagan gods of Rome and the emperors who made themselves gods ruled the people with an attitude of total and merciless authority. These new Christians that preached peace and love often found themselves facing death in the arena when they refused to worship the emperor or his gods. The empire unknowingly aided the growth of this new faith. Every attempt to stop the spread of Christianity with the threat of persecution and death seemed to encourage more converts. These converts began to realize that the pain and terror inflicted in the arena was at odds with the gentle and merciful words of their new religion. Notice the cause-and-effect chain of events in this paragraph. Notice, too, how this major section of the text contributes to the ideas in the text as a whole and to the development of new ideas. In the first sentence, “the rise of a new faith” (the cause) led to a change in attitudes (the effect). This effect then became a cause that led to the stopping of the combat between gladiators (an effect). In the sixth sentence, “[e]very attempt to stop the spread of Christianity” (the cause) “encourage[d] more converts” (the effect). By using cause-and-effect text structure in this paragraph, Watkins is developing the idea that the rise of a new faith led to the fall of the tradition of the gladiator in Ancient Rome.