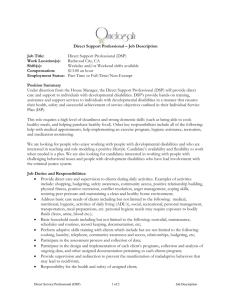

Research in Developmental Disabilities 28 (2007) 353–361

Functional assessment of challenging behavior:

Toward a strategy for applied settings

Johnny L. Matson *, Noha F. Minshawi

Department of Psychology, Louisiana State University, 236 Audubon Hall Baton Rouge,

LA 70803-5501, United States

Received 28 August 2005; received in revised form 1 December 2005; accepted 5 January 2006

Abstract

The development of experimental functional analysis and more recently functional analysis checklists

have become common technologies for evaluating antecedent events and the consequences of problematic

behaviors. Children and developmentally disabled persons across the life span with challenging behaviors

have been the primary focus of this research. The primary purpose of this paper is to present an overview the

developments in this rapidly expanding research literature, particularly as it involves the application of the

functional assessment paradigm in applied settings where resources and time are scarce. Implication of the

functional assessment research for clinical practice are discussed along with strengths and weakness of the

current technology.

# 2006 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved.

Keywords: Functional analysis; QABF; Experimental functional analysis

1. Functional assessment of challenging behavior: toward a strategy of application in

applied settings

The purpose of functional assessment in the applied literature has been to identify maintaining

contingencies for aberrant or challenging behavior in the person’s environment (O’Reilly, 1997).

A variety of means for establishing these operations have been described. Most frequently

studied in terms of number of papers have been analogue sessions, where direct observation of

potential maintaining variables systematically manipulated by the experimenter occurs. This

methodology has also been referred to as experimental functional analysis (EFA). A steady

stream of articles have appeared over the past 20 years, refining methods, and describing various

* Corresponding author.

E-mail address: johnmatson@aol.com (J.L. Matson).

0891-4222/$ – see front matter # 2006 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved.

doi:10.1016/j.ridd.2006.01.005

354

J.L. Matson, N.F. Minshawi / Research in Developmental Disabilities 28 (2007) 353–361

applications of this technology. Length of time of the assessment and other technical constraints

have resulted in abbreviated versions of this technology and have resulted in other researchers

attempting to develop alternative methods of identifying maintaining variables.

More recently, checklists that describe the conditions presented in the experimental functional

analysis literature have emerged. Most notable among these scales are the motivation assessment

scale (MAS) and Questions About Behavior Function (QABF). These scales provide an

additional dimension to the overall literature. The number of studies using these measures,

particularly the QABF, is increasing.

Scatter plots have also been mentioned. The classic paper of Touchette, MacDonald, and

Langer (1985) is the model for application of this technology in many applied settings. However,

while this method has received attention in applied settings, it has been virtually ignored in the

research literature. Therefore, the psychometric properties for accurately establishing

maintaining operations of problem behavior with this approach are unknown. Additionally,

given this paucity of research, scatter plots will not be a focus for this review. There simply is not

a sufficient literature to review.

A fourth method that also has considerable promise is the functional analysis interview

(O’Neill et al., 1997). With this method, the clinician can ask a series of semi-structured

questions with open ended answers as a means of determining environmental events, medical

conditions and other mediating factors that could lead to the person’s challenging behaviors. As

with scatter plots, a research literature has not been established to validate this approach to

functional assessment. Promise exists, however, and hopefully some innovative scholars will

explore the topic in the future. As with scatter plots, though, structured interviews will not be the

focus of this review given the lack of data based studies.

At present then, researchers and practitioners are guided toward EFA and/or checklists as a

means of conducting functional assessments with established psychometric properties. As the

area evolves and efforts to apply these methods in the broad context of school, community living

and institutional settings grow, pragmatic issues of implementation become of greater and greater

concern. The development and application of these two means of functional assessment and their

application in applied settings will be the focus of our review.

2. Experimental functional analysis

The first demonstration of a functional analysis according to Risley (2005) was reported by

Montrose Wolfe and associates (Wolfe, Birnbauer, Lawler, & Williams, 1970; Wolfe,

Birnbauer, Williams, & Lawler, 1965). They treated a severe behavior problem, vomiting, which

the authors demonstrated was maintained by escape (returning her to the dormitory). The focus

on identifying maintaining variables for learning-based treatments has a long history relative to

the application of behavioral methodology in general. However, a focused technology on

functional assessment research did not begin to develop until almost 20 years after this study was

published.

Brian Iwata and his associates have been the primary drivers behind the development of the

EFA technology. While others have published early work on the topic (Carr, 1977; Carr,

Newsom, & Binkoff, 1980), the paper by Iwata, Dorsey, Slifer, Bauman, and Richman (1982)

was the key publication that most authors point to as the seminal early paper on the topic. In this

paper, the authors described the application of operant technology to the environmental events

via in vivo presentation of various antecedent and consequent events. This early paper was based

on nine persons with developmental disabilities and self-injurious behavior. The three conditions

J.L. Matson, N.F. Minshawi / Research in Developmental Disabilities 28 (2007) 353–361

355

to which each individual was exposed were play materials (present versus absent), experimental

demands (high versus low) and social attention (absent versus noncontingent versus contingent).

This study was followed by many others. Iwata and associates are to be commended for their

persistence in publishing on the topic. Without their efforts, the functional assessment literature

as we know it would have been unlikely to develop or it would have developed at a much slower

rate.

Hanley, Iwata, and McCord (2003) suggested that functional analysis has become the

hallmark of behavioral assessment. We would not go that far, but certainly it is a topic that has

received a great deal of attention, particularly in the Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, where

these authors report that 180 of the total 277 studies using this methodology have been published.

The trend in this regard shows no sign of slowing.

With some modifications, most studies have used the EFA procedures described by Iwata et al.

(1982). Assessment sessions are conducted in an analogue setting where the person’s challenging

behavior or behaviors can be directly observed. The person is presented with a control condition,

play condition and two to four experimental conditions consisting of escape (from the presenting

stimuli), being left alone, being given attention for the challenging behavior, and being given a

tangible item when the maladaptive behavior occurs. Often the tangible is a food item. In Derby

et al. (2000), for example, where children with potential multiple functions of their maladaptive

behavior existed, 10 sessions of each condition were conducted. We calculate this as 30–50

sessions per child, a very labor-intensive method.

Using variations of the method described above, many studies with young children have been

conducted (e.g., Broussard & Northup, 1997; Fisher, Adelinis, Thompson, Wordsell, & Zarcone,

1998; Kennedy, 1994; Martin, Gaffan, & Williams, 1999; Thompson, Fisher, Piazza, & Kuhn,

1998). Additional efforts have also been made to expand this technology to other groups. For

example, Carr, Hatfield, Austin, and Bailey (1998) found that attention was a maintaining

variable for the aggression of a 33-year-old female diagnosed with severe mental retardation and

organic psychosis.

These studies typically include two to four participants, rarely more. However, the sheer

number of studies conducted with the EFA technology suggests that many, if not most,

individuals assessed will display some form of maintaining function. Some research has also

been conducted linking intervention to these assessment data. However, this literature is much

more limited than the research on identifying maintaining variables only.

The impracticality of the EFA in most settings, due to the substantial resource and time

allotments needed (Moore et al., 2002), has been tacitly acknowledged by those in the applied

behavior analysis area. This acknowledgement is best exemplified by efforts to develop a ‘‘brief

functional analysis’’ (Northup et al., 1991; Wallace & Knights, 2003). Basically, the major

modification involves shortening session length. For example, Wallace and Knights (2003)

described an extended or standard functional analysis presentation of a condition from 10 to

12 min. Even so, they described 27–34-condition presentation for their participants. We calculate

54–68 ‘‘in session’’ minutes in the brief EFA versus 270 (4.5 h) to 340 (5.7 h) ‘‘in session’’ for the

extended assessment. These calculations do not count set-up time, training of the assessment

personnel, time between conditions, etc., therefore, a conservative estimate is that a brief

assessment may take 2–3 and 6–8 h for a standard assessment to complete, versus 15–20 min for

a checklist. Additionally, the checklist does not require an assessment room, reinforcers (which

many agencies do not have the money to buy) or the same level of staff training.

Other compelling reasons to look for alternatives to the EFA at least for most applied

applications, has led to the development of scaling methods for a functional assessment. Scaling

356

J.L. Matson, N.F. Minshawi / Research in Developmental Disabilities 28 (2007) 353–361

has a long established tradition in psychology, and has been used to assess a wide range of areas

from intelligence to psychopathology to social skills (Anastasi & Urbina, 1997).

3. Checklists for functional assessment (CFA)

While the EFA technology has much to recommend it, the labor-intensive nature of the

procedure and the high level of expertise needed to carry out the methods have limited its utility.

As a result, investigators have explored alternative means of acquiring the same type of

information on maintaining variables. The primary rules of operation are that the method must be

fast and require minimal expertise. A method of this sort would be a major success, even if only a

handful of cases could be correctly identified, since such a result would allow for more resource

allocation to more difficult/complex cases with respect to maintaining variables. As noted,

functional analysis interviews and scatter plots have been two methods researchers have

proposed to fill this niche. However, to date research on these methods has not been forthcoming.

The same cannot be said of checklists.

3.1. Motivation assessment scale (MAS)

The MAS (Durand & Crimmins, 1988), has earned the distinction of being the first functional

assessment checklist to appear in the literature. As a result, these authors deserve the credit for

establishing the potential value of this assessment method for identifying maintaining variables

for challenging behaviors. The MAS consisted of questions aimed at determining if attention or

other variables could be identified for challenging behavior.

Reliability studies carried out soon after the development of the MAS proved to be

disappointing (Newton & Sturmey, 1991; Zarcone, Rodgers, Iwata, Rourke, & Dorsey, 1991).

However, the scale was a very important first step in establishing an alternative to EFAs in clinical

settings.

3.2. Questions about behavior function (QABF)

The MAS was an important new development since it provided the first practical means of

conducting a functional assessment of client problem behavior on a broad scale in applied

settings. However, psychometric problems with reliability surfaced and validity data was not

established. Enter the QABF (Matson & Vollmer, 1995), which included the primary functions

established via the EFA literature but using a format similar to the MAS.

At this writing, the QABF has a substantial data base to support its use in applied settings. This

scale consists of 25 items rated from one to three, occur to does not occur. Five factor analyzed

subscales have been established: escape, attention, nonsocial, tangible and problem behavior

related to pain (Paclawskyj, Matson, Rush, Smalls, & Vollmer, 2000). In Paclawskyj et al.’s

(2000) experiment, 34 persons with severe or profound ID were tested on test–retest reliability

and 57 people were tested for interrater reliability. Pearson product–moment correlations on test–

retest were .795–.990 ( p < .01) for total and subtest scores. Using the same calculation methods,

interrater reliability was also uniformly high. In the second experiment, Paclawskyj et al. (2000)

studied 243 adults with severe or profound ID to test the internal consistency of the subscales.

Coefficient alpha for subscale scores ranged from .9 to .928 and the total score coefficient alpha

was .601. These latter data are good in that subscale internal correlations should be higher than

the total score. If this were not the case, statistically speaking, one would not have subscales.

J.L. Matson, N.F. Minshawi / Research in Developmental Disabilities 28 (2007) 353–361

357

Additionally, reliability data has been collected with acceptable test–retest, interrater and internal

reliability (Shogren & Rojahn, 2003).

Nicholson et al. (in press) in the most recently conducted assessment of psychometric properties

of the QABF completed a scale for 118 problem behaviors (mean of 2.95 per individual) across 20

intellectually disabled persons between 10 and 26 years of age and averaging 17.6 years. The

authors concluded that item and subscale interrater reliability were modest but exceeded those of

comparable assessments. They also concluded that interrater agreement was higher for higher rated

behavior and lower for maladaptive (versus disruptive or destructive) behaviors. Their factor

analysis replicated a previous analysis (Paclawskyj, Matson, Rush, Smalls, & Vollmer, 2001).

Internal consistency of the scales was high. In Matson, Bamburg, Cherry, and Paclawskyj (1999)

they generally reported higher reliability than from Nicholson et al. (in press). The authors noted at

this latter study that their raters had less formal training and bachelors level or direct care staff

versus masters level psychologists were employed. This factor may have been a contributor.

However, we suspect that an even bigger issue is that Matson et al. (1999) studied persons with one

problem behavior while Nicholson et al. (in press) studied persons with multiple problem

behaviors. It is likely that this variable might be quite important in any efforts to establish

maintaining operations of a problem behavior. This issue certainly warrants further investigation

regardless of the functional assessment methodology used.

Psychometric properties of the QABF have also been extended to the mentally disabled

population. Singh et al. (in press) tested 135 adults with serious mental illness from three

inpatient psychiatric hospitals. Their factor analysis was identical to the Paclawskyj et al. (2000)

findings. Across the five factors of physical discomfort, social attention, tangible reinforcement,

escape and non-social, interrater reliability ranged from .96 to .98 and Pearson r test–retest

reliability ranged from .86 to .99. Coefficient alpha suggested substantial internal consistency

(.84 to .92) for the target behaviors of aggression and property destruction. The authors also

pointed out that while analogue functional analyses have considerable utility for persons with

developmental disabilities, it would not be possible to use this method for those of normal

intellectual functioning and mental illness on practical grounds.

The validity study that best supports the utility of the QABF in applied settings included a

sample of 398 adults with intellectual disability (Matson et al., 1999). From this sample, 118

individuals evinced self-injury, 83 had aggression and 197 evinced stereotypies. Persons with

more than one of these three challenging behaviors were excluded to ensure a clearer test of

function. The QABF resulted in establishing a function for 83% of the self-injury group, 74% of

persons with aggression and 93% of those in the stereotypy group.

Past two of the study tested 180 people, 60 with each of the three challenging behaviors. Thirty

persons with self-injury, aggression or stereotypy had behavioral treatment based on functions of

the behavior identified with the QABF, while 30 in each challenging behavior group were

prescribed an intervention package of interrupting the aberrant behavior, blocking the behavior,

and redirecting the person to an appropriate task. Treatment was over 6 months, which is

significantly longer than most studies using functional assessment and the persons treated were

adults, in real world settings who evinced these challenging behaviors for many years. Again, this

research differs from many of the functional assessment studies where young children with very

mild problem behaviors are assessed. The result from the study demonstrated significantly

greater effects, with the treatments tailored to the function of the problem behavior versus a

general treatment package. In this respect, the QABF data support validity studies using EFA

procedures. That is, functional assessment is helpful in tailoring more efficient and effective

treatment to client problems.

358

J.L. Matson, N.F. Minshawi / Research in Developmental Disabilities 28 (2007) 353–361

Some overlap in EFA and QABF results have been noted, which is good news for the clinician

who is short on time and resources. Paclawskyj et al. (2001) evaluated the convergent validity of

the QABF with EFA and MAS data. They studied 13 adults with profound intellectual disabilities

who evinced self-injury, aggression and stereotypies. The QABF resulted in identification of 16

primary functions for problem behavior, with the challenging behavior of three people having

two primary functions. The EFA which followed parameters established by Iwata et al. (1982)

resulted in 13 primary functions being identified, with two primary functions for 3 of 10 cases.

Overlap of the two methods producing the same function was 56%. However, when the cases

with no identified function by either method were excluded, a 75% overlap in identified functions

was noted.

Hall (in press) assessed four adults with intellectual disability using the QABF and EFA using

the Iwata et al. (1982) methodology. Hall (in press) reported agreement in identify problem

behavior antecedents at 75%, replicating Paclawskyj et al. (2001) data.

More recently, behaviors other than property destruction, aggression, self-injury and

stereotypy have been studied with the QABF. As such, these data follow similar efforts in the

EFA literature where a host of target behaviors have been assessed (e.g., Carr, Sidener, & Sidener,

2005; Girolami & Scotti, 2001; Valdovinos, Roberts, & Kennedy, 2004). For example,

Applegate, Matson, and Cherry (1999) studied 30 people with pica and 18 with rumination.

Nonsocial was the dominant function identified.

Matson et al. (2005) studied 125 intellectually disabled people with pica, rumination, food

stealing, food refusal and mealtime problems (e.g., aggression, self-injury). Escape was most

often associated with food refusal and mealtime problems, pica and rumination were most often

associated with a non-social function, while a tangible function typically motivated food stealing

and food refusal. Food refusal appeared to be due to physical discomfort in most cases.

The QABF, by its nature, is brief and fairly general. This goal is also accomplished by using a

Likert three-point rating scale. As a result, some functions of maladaptive behavior may not be

identified. As a result, Matson et al. (2003) have developed a forced-choice functional analysis

scale, the functional assessment for multiple CausaliTy (FACT), to be used when the QABF does

not yield a clear function. Internal consistency in this initial study was good to excellent and the

factor structure was similar to the QABF. However, additional research on the value of this

measure in identifying function or functions of maladaptive behavior are under way.

3.3. Clash of methodologies

How professionals at this point choose to do a functional assessment appears to have as much

to do with one’s theoretical world view of clinical practice as it does data. Those who espouse a

strong orientation toward applied behavior analysis are likely to rely almost exclusively on EFA

methodology. Checklists are indirect measures of behavior, and are subject to the inaccurate

perceptions of the rater/informant, a valid criticism. Persons with a more ‘‘traditional’’ view of

psychometrics are likely to be concerned, but less concerned than those with a strong applied

behavior analysis perspective relative to this point.

For those who are most interested in applied behavior analysis methodology, there is an

implicit assumption that the EFA methodology is superior to other methods. For example,

checklists are referred to as ‘‘supplemental functional assessments’’ (Hanley et al., 2003). We

would argue that such value laden judgments await further empirical verification. At this point,

the small amount of studies making direct comparisons between EFA and CFA or which test CFA

reliability and validity lead to the opposite conclusion. However, researchers await further

J.L. Matson, N.F. Minshawi / Research in Developmental Disabilities 28 (2007) 353–361

359

confirmation of methods for given problems and topographies of behavior to determine what

means are best for a given person’s problems.

The time commitment of the EFA technology is hard to get around. Thus, even the most ardent

EFA proponents have recently been experimenting with ‘‘brief EFA’’ methods (e.g., Wacker,

Berg, & Harding, 2004; Wallace & Knights, 2003). Again, EFA technology may prove to be

superior to CFA methods in some instances once the research is complete. However, the time and

expertise needed by the assessor is hard to overcome.

The EFA has other problems that also warrant attention in the future. For example, the

repeated presentation of maintaining contingencies may identify maintaining variables but it is

also possible that the assessment may strengthen existing maintaining factors and/or introduce

new ones. Second, by the nature of the assessment, the maladaptive behavior is introduced and

then reinforced. This procedure may result in increased rates of the maladaptive behavior for

some period of time following termination of the EFA. As a result, clients and staff in the

immediate proximity of the person being assessed are at some additional risk for personal

harm when aggression, self-injury and noncompliance are evaluated. Third, as Singh et al. (in

press) noted, adults with normal intellectual functioning and possibly some individuals with

ID as well, are likely to ‘‘figure out’’ the parameters of the EFA and refuse to participate.

Fourth, ratings are based on direct observations, but direct observations in a highly contrived

analogue setting. Tasks, the room and the staff who are interacting with the individual are not

typical. Thus, generalizability of the results to real world situations cannot be assumed. Fifth,

very high intensity, low frequency behaviors (e.g., severe aggression) are unlikely to be

evinced during the assessment. If the behavior is elicited it is likely to result in durations far

longer than the brief 2–10 min sessions typically used as assessment conditions. The risk of

harm for client and staff would be considerable. Sixth, while the validity of EFA technology

has to some degree been established in small N studies where identified maintaining functions

have been established, much more needs to be done before EFA can be described as a valid

technology. To our knowledge, no group comparisons of EFA to no functional assessment

studies have been conducted. While a massive study such as the validity paper of Matson et al.

(1999) is unlikely, group data with smaller group sizes would still be a substantial addition to

the literature.

Functional assessment appears to be evolving into two camps, those who prefer EFA and those

who prefer CFA technology. The EFA methods are more likely to find wide acceptance in

smaller, more labor intensive applied settings, such as small university-based inpatient units and

private schools for children with developmental disabilities. CFA methods have become more

popular in developmental centers, group home operations and more recently inpatient psychiatric

hospitals, where fewer resources are available. The field of developmental disabilities is large,

and there appears to be plenty of room for both methodologies. The more immediate issue is to

make practitioners aware of the benefits of functional assessment methods in assessment and

treatment. Much ground has yet to be covered in this regard.

References

Anastasi, A., & Urbina, S. (1997). Psychological testing (7th ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

Applegate, H., Matson, J. L., & Cherry, K. E. (1999). An evaluation of functional variables affecting problem behaviors in

adults with mental retardation using the questions about behavior function (QABF). Research in Developmental

Disabilities, 20, 229–238.

Broussard, C., & Northup, J. (1997). The use of functional analysis to develop peer interventions for disruptive classroom

behaviors. School Psychology Quarterly, 12, 65–76.

360

J.L. Matson, N.F. Minshawi / Research in Developmental Disabilities 28 (2007) 353–361

Carr, E. G. (1977). The motivation of self-injurious behavior: A review of some hypotheses. Psychological Bulletin, 84,

800–816.

Carr, J. E., Hatfield, D. B., Austin, J. L., & Bailey, J. S. (1998). Interpreting functional analysis results using the real-time

recording of independent and dependent variables. Behavioral Interventions, 13, 61–66.

Carr, E. G., Newsom, C. D., & Binkoff, J. A. (1980). Escape as a factor in the aggressive behavior of two retarded children.

Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 13, 101–117.

Carr, E. G., Sidener, T. M., & Sidener, D. W. (2005). Functional analysis and habit-reversal treatment of tics. Behavioral

Interventions, 20, 185–202.

Derby, K. M., Hagopian, L., Fisher, W. W., Richman, D., Augustine, M., Fahs, A., et al. (2000). Functional analysis of

aberrant behavior through measurement of separate response topographies. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 33,

113–117.

Durand, V. M., & Crimmins, D. G. (1988). Identifying the variables maintaining self-injurious behavior. Journal of Autism

and Developmental Disorders, 18, 99–117.

Fisher, W. W., Adelinis, J. D., Thompson, R. H., Wordsell, A. S., & Zarcone, J. R. (1998). Functional analysis and

treatment of destructive behavior maintained by termination of don’t (and symmetrical ‘‘do’’) requests. Journal of

Applied Behavior Analysis, 31, 339–356.

Girolami, P. A., & Scotti, J. R. (2001). Use of analog functional analysis in assessing the function of mealtime behavior

problems. Education and Training in Mental Retardation and Developmental Disabilities, 36, 207–223.

Hall, S. (in press). Comparing descriptive, experimental and informant-based assessment of problem behaviors. Research

in Developmental Disabilities.

Hanley, G. P., Iwata, B. A., & McCord, B. E. (2003). Functional analysis of problem behavior: A review. Journal of

Applied Behavior Analysis, 36, 147–185.

Iwata, B. A., Dorsey, M. F., Slifer, K. J., Bauman, K. E., & Richman, G. S. (1982). Toward a functional analysis of selfinjury. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 27, 197–209.

Kennedy, C. H. (1994). Manipulating antecedent conditions to alter the stimulus control of problem behavior. Journal of

Applied Behavior Analysis, 27, 161–170.

Martin, N. T., Gaffan, E. A., & Williams, T. (1999). Experimental functional analysis for challenging behavior: A study of

validity and reliability. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 20, 125–146.

Matson, J. L., & Vollmer, T. (1995). Questions about behavioral function (QABF). Baton Rouge, LA: Disability

Consultants, LLC.

Matson, J. L., Bamburg, J. W., Cherry, K. E., & Paclawskyj, T. R. (1999). A validity study on the questions about

behavioral function (QABF) scale: Predicting treatment success for self-injury, aggression, and stereotypies. Research

in Developmental Disabilities, 20, 163–176.

Matson, J. L., Kuhn, D. E., Dixon, D. R., Mayville, S. B., Laud, R. B., Cooper, C. L., et al. (2003). The development and

factor structure of the Functional Assessment for multiple CausaliTy (FACT). Research in Developmental Disabilities, 24, 485–495.

Matson, J. L., Mayville, S. B., Kuhn, D. E., Sturmey, P., Laud, R., & Cooper, C. (2005). The behavioral function of feeding

problems as assessed by the questions about behavior function (QABF). Research in Developmental Disabilities, 26,

399–408.

Moore, J. W., Edwards, R. P., Sterling-Turner, H. E., Riley, J., DuBard, M., & McGeorge, A. (2002). Teaching acquisition

of functional analysis methodology. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 35, 73–77.

Newton, J. T., & Sturmey, P. (1991). The motivation assessment scale: Interrater reliability and internal consistency in a

British sample. Journal of Mental Deficiency Research, 35, 472–474.

Nicholson, J., Konstantinidi, E., & Furniss, F. (in press). On some psychometric properties of the questions about behavior

function (QABF). Research in Developmental Disabilities.

Northup, J., Wacker, D., Sasso, G., Steege, M., Cigrand, K., Cooke, J., et al. (1991). A brief functional analysis

of aggression and alternative behavior in an outclinic setting. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 24, 509–

522.

O’Neill, R. E., Horner, R. H., Albin, R. W., Sprague, J. R., Storey, K., & Newton, J. S. (1997). Functional assessment and

program development for problem behavior. Pacific Grove, CA: Brooks/Cole Publishing.

O’Reilly, M. F. (1997). Functional analysis of episodic self-injury correlated with recurrent otitis media. Journal of

Applied Behavior Analysis, 30, 165–167.

Paclawskyj, T. R., Matson, J. L., Rush, K. S., Smalls, Y., & Vollmer, T. R. (2000). Questions about behavioral function

(QABF): A behavioral checklist for functional assessment of aberrant behavior. Research in Developmental

Disabilities, 21, 223–229.

J.L. Matson, N.F. Minshawi / Research in Developmental Disabilities 28 (2007) 353–361

361

Paclawskyj, T. R., Matson, J. L., Rush, K. S., Smalls, Y., & Vollmer, T. R. (2001). Assessment of the convergent validity of

the questions about behavioral function scale with analogue functional analysis and the motivation assessment scale.

Journal of Intellectual Disability Research, 45, 484–494.

Risley, T. (2005). Montrose M. Wolf. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 38, 279–287.

Shogren, K. A., & Rojahn, J. (2003). Convergent reliability and validity of the questions about behavior function and the

motivation assessment scale: A replication study. Journal of Developmental and Physical Disabilities, 15, 367–375.

Singh, N. N., Matson, J. L., Lancing, G. E., Singh, A. N., Adkins, A. D., McKeegan, G. F., et al. (in press). Questions

About Behavior Function in Mental Illness (QABFMI): A behavior checklist for functional assessment of maladaptive

behavior exhibited by individuals with mental illness. Behavior Modification.

Thompson, R. H., Fisher, W. W., Piazza, C. S., & Kuhn, D. E. (1998). The evaluation and treatment of aggression

maintained by attention and automatic reinforcement. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 31, 103–116.

Touchette, P. E., MacDonald, R. F., & Langer, S. N. (1985). A scatter plot for identifying stimulus control of problem

behavior. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 18, 343–351.

Valdovinos, M. G., Roberts, C., & Kennedy, C. H. (2004). Analogue functional analysis of movements associated with

tardive dyskinesia. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 37, 391–393.

Wacker, D., Berg, W., & Harding, J. (2004). Use of brief experimental analysis in outpatient clinic and home settings.

Journal of Behavioral Education, 13, 213–226.

Wallace, M. D., & Knights, D. J. (2003). An evaluation of a brief functional analysis format within a vocational setting.

Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 36, 125–128.

Wolfe, M. M., Birnbauer, J., Lawler, J., & Williams, T. (1970). The operant extinction, reinstatement and re-extinction of

vomiting behavior in a retarded child. In Ulrich, R., Stachnik, T., & Marby, J. Eds. Control of human behavior. vol. 2

(pp.146–148). Glenview, IL: Scott Foresman.

Wolfe, M. M., Birnbauer, J., Williams, T., & Lawler, J. (1965). A note on operant extinction of the vomiting behavior of a

retarded child. In L. P. Ullman, & L. Krasner (Eds.), Case studies in behavior modification (pp. 364–366). New York:

Holt, Rinehart, & Winston.

Zarcone, J. R., Rodgers, T. A., Iwata, B. A., Rourke, D. A., & Dorsey, M. F. (1991). Reliability analysis of the motivation

assessment scale: A failure to replicate. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 12, 349–360.