Adams and Jefferson

advertisement

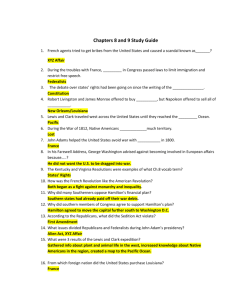

Early National Period Highlights by Alan Brinkley What follows is a highly subjective selection of events in the period 1796 to 1812. This reading is excerpted from Chapters Six and Seven of Brinkley’s American History: A Survey (10th ed.). I wrote the footnotes. If you use the questions below to guide your note taking (which is a good idea), please be aware that several of the questions have multiple answers. Study Questions 1. Why did the US fight a “quasi-war” with France? And what is a “quasi war,” anyway? 2. Why did Federalists pass the Alien and Sedition Acts? 3. Why did Republicans oppose these two laws so forcefully? 4. According to the Virginia and Kentucky Resolutions, why could states nullify acts passed by Congress? 5. How revolutionary was the “Revolution of 1800”? Did Jefferson substantially change the policies of his Federalist predecessors? 6. Was Jefferson right to question his authority to purchase Louisiana? Why or why not? THE DOWNFALL OF THE FEDERALISTS The Federalists’ impressive triumphs [during the Washington administration] did not ensure their continued dominance in the national government. On the contrary, success seemed to produce problems of its own—problems that eventually led to their downfall. Since almost all Americans in the 1790s agreed that there was no place in a stable republic for an organized opposition, the emergence of the Republicans as powerful contenders for popular favor seemed to the Federalists a grave threat to national stability. Beginning in the late 1790s, when major international perils confronted the government as well, the Federalists could not resist the temptation to move forcefully against the opposition. Facing what they believed was a stark choice between respecting individual liberties and preserving stability, the Federalists chose stability. The result was political disaster. After 1796, the Federalists never won another election…. The Election of 1796 Despite strong pressure from his many admirers to run for a third term as president, George Washington insisted on retiring from office in 1797…. With Washington out of the running, no obstacle remained to an open expression of the partisan rivalries that had been building over the previous eight years. Jefferson was the uncontested candidate of the Republicans in 1796. The Federalists faced a more difficult choice. Hamilton, the personification of Federalist, had created too many enemies to be a credible candidate. So Vice President John Adams, who had been directly associated with none of the unpopular Federalist measures, became his party’s nominee for president. [Because of internal Federalist conflicts,] Jefferson finished second in the balloting and became vice president. (The Constitution provided for the candidate receiving the second highest number of electoral votes to become vice president—hence the awkward result of men from different parties serving in the nation’s two highest elected offices. The Twelfth Amendment, adopted in 1804, reformed the electoral system to prevent such situations.) Adams thus assumed the presidency under inauspicious circumstances. He presided over a divided party which faced a strong and resourceful Republican opposition committed to its extinction. Adams himself was not even the dominant figure in his own party; Hamilton remained the most influential Federalist…. Austere, rigid, aloof, [Adams] had little talent at conciliating differences, soliciting support, or inspiring enthusiasm…. He seemed to assume that his own virtue and the correctness of his positions would alone be enough to sustain him. He was usually wrong. The Quasi War with France American relations… with revolutionary France quickly deteriorated. French vessels capture American ships on the high seas and at times imprisoned the crews…. Some of President Adams’s advisers favored war… but Hamilton recommended conciliation, and Adams agreed. In an effort to stabilize relations, Adams appointed a bipartisan commission… to negotiate with France. When the Americans arrived in Paris in 1797, three agents of the French foreign minister, Prince Talleyrand, demanded a loan for France and a bribe for French officials before any negotiations could begin.1 … When Adams heard of the incident, he sent a message to Congress denouncing the French insults and urging preparations for war. He then turned the report of the American commissioners over to Congress, after deleting the names of the three French agents and designating them only as “Mssrs. X, Y, and Z.” When the report was published, it created widespread popular outrage at france’s actions and strong support for the Federalists’ response. For nearly two years after the “XYZ Affair,” as it became known, the United States found itself engaged in an undeclared war with France. Adams persuaded Congress to cut off all trade with France, to repudiate the treaties of 1778,2 and to authorize American vessels to capture French armed ships on the high seas…. The United States also began cooperating closely with the British and became virtually an ally of Britain in the war with France. In the end, France chose to conciliate the United States before the conflict grew. Adams sent another commission to Paris in 1800, and the new French government (headed now by “first consul” Napoleon Bonaparte) agreed to a treaty with the United States that canceled the old agreement of 1778 and established new commercial arrangements. As a result, the “quasi war” came to a reasonably peaceful end…. Repression and Protest The conflict with France helped the Federalists increase their majorities in Congress in 1798. Armed with this new strength, they began to consider ways to silence the Republican opposition. The result was some of the most controversial legislation in American history: the Alien and Sedition Acts. 1 Talleyrand was renowned for such self-dealing. He would later serve as Napoleon’s foreign minister, and Napoleon once said to him “vous êtes de la merde dans un bas de soie.” (You can look it up.) 2 These established the Franco-American alliance through which the French helped us defeat Britain in the Revolutionary War. The end of the alliance would signal the last time the United States would formally ally with any nation until World War II. The Alien Act placed new obstacles in the way of foreigners who wished to become American citizens, and it strengthened the president’s hand in dealing with aliens. The Sedition Act allowed the government to prosecute those who engaged in “sedition” against the government.3 In theory only libelous or treasonous activities were subject to prosecution; but since such activities were subject to widely varying definitions, the law made it possible for the federal government to stifle virtually any opposition. The Republicans interpreted the new laws as part of a Federalist campaign to destroy them and fought back. President Adams signed the new laws but was cautious in implementing them. He did not deport any aliens, and he prevented the government from launching a major crusade against the Republicans. But the legislation had a significant repressive effect nevertheless…. [T]he administration made use of the Sedition Act to arrest and convict ten men, most of them Republican newspaper editors whose only crime had been to criticize the Federalists in government. Republican leaders pinned their hopes for a reversal of the Alien and Sedition Acts on the state legislatures. (The Supreme Court had not yet established its sole right to nullify congressional legislation, and there were many who believed that the states had that power, too.) The Republicans laid out a theory for state action in two sets of resolutions in 1798-1799, one written (anonymously) by Jefferson and adopted by the Kentucky legislature and the other drafted by Madison and approved by the Virginia legislature. The Virginia and Kentucky Resolutions, as they were known, [argued] that the federal government had been formed by a “compact” or contract among the states and possessed only certain delegated powers. Whenever it exercised any undelegated powers, its acts were “unauthoritative, void, and of no force.” If the parties to the contract, the states, decided that the central government had exceeded those powers, the Kentucky Resolution claimed, they had the right to “nullify” the appropriate laws. The “Revolution” of 1800 These bitter controversies shaped the 1800 presidential election. The presidential candidates were the same as four years earlier: Adams for the Federalists, Jefferson for the Republicans. But the campaign of 1800 was very different from the one preceding it. Indeed, it may have been the ugliest in American history… The Federalists accused Jefferson of being a dangerous radical and his followers of being wild men who, if they should come to power, would bring on a reign of terror comparable to that of the French Revolution. The Republicans portrayed Adams as a tyrant conspiring to become king, and they accused the Federalists of plotting to subvert human liberty and impose slavery on the people…. The election was close, and, [after considerable electoral shenanigans involving Aaron Burr, Jefferson’s vice presidential running mate, that would result in a fatal enmity between Burr and Alexander Hamilton,] Jefferson was elected. After the election of 1800, the only branch of the federal government left in Federalist hands was the judiciary. The Adams administration spent its last months in office taking steps to make the party’s hold on the courts secure. By the Judiciary Act of 1801, passed by the lame duck Congress, the Federalists reduced the number of Supreme Court justices by one but greatly 3 Sedition: speech intended to encourage people to rebel. increased the number of federal judgeships as a whole. Adams quickly appointed Federalists to the newly created positions. Indeed, there were charges that he stayed up until midnight on his last day in office to finish signing the new judges’ commissions. These officeholders became known as the “midnight appointments.” Even so, the Republicans viewed their victory as almost complete. The nation, they believed, had been saved from tyranny. A new era could now begin, one in which the true principles on which America had been founded would once again govern the land. The exuberance with which the victors viewed the future—and the importance they attributed to the Federalists’ defeat —was evident in the phrase Jefferson himself later used to describe his election. He called it the “Revolution of 1800.” It remained to be seen how revolutionary it would really be. JEFFERSON THE PRESIDENT Privately, Thomas Jefferson may well have considered his victory over John Adams in 1800 to be what he later termed it: a revolution “as real… as that of 1776.” Publicly, however, he was restrained and conciliatory at the time, attempting to minimize the differences between the two parties and to calm the passions that the bitter campaign had aroused. “We are all republicans, we are all federalists,” he said in his inaugural address. And during his eight years in office, he did much to prove those words correct. There was no complete repudiation of Federalist policies…. Indeed, at times Jefferson seemed to outdo the Federalists at their own work—most notably in overseeing a remarkable expansion of the territory of the United States. In some respects, however, the Jefferson presidency did indeed represent a fundamental, if temporary, change in the direction of the federal government. The new administration oversaw a drastic reduction in the powers of some national institutions, and it forestalled the development of new powers in areas where the Federalists would certainly have attempted to expand them. Neither the executive nor the legislative branch of government was willing or able to exercise decisive authority in most areas of national life by the end of the Jeffersonian era. Only the courts continued trying to assert federal power in the ways the Federalists had envisioned…. President and Party Leader ...Jefferson was, above all, a shrewd and practical politician. On the one hand, he went to great lengths to eliminate the aura of majesty surrounding the presidency that he believed his predecessors had created. He decided, for example, to submit his messages to Congress not by delivering them in person, as Washington and Adams had done, but by sending them in writing, thus avoiding even the semblance of attempting to dictate to the legislature. (The precedent he established survived for more than a century, until the administration of Woodrow Wilson.) At the same time, however, Jefferson worked hard to exert influence as the leader of his party, giving direction to Republicans in Congress by quiet and sometimes even devious means. To his cabinet he appointed members of his own party who shared his philosophy…. Although the Republicans had objected strenuously to the efforts of their Federalist predecessors to build a network of influence through patronage, Jefferson, too, used his powers of appointment as an effective political weapon. Like Washington before him, he believed that federal offices should be filled with men loyal to the principles and policies of the administration. He did not attempt a sudden and drastic removal of Federalist officeholders, but at every convenient opportunity he replaced the holdovers from the Adams administration with his own trusted followers. By the end of his first term about half the government jobs, and by the end of his second term practically all of them, were in the hands of loyal Republicans. When Jefferson ran for reelection in 1804, he won overwhelmingly. The Federalist presidential nominee, Charles C. Pinckney, could not even carry most of the party’s New England strongholds. Jefferson won 162 electoral votes to Pinckney’s 14, and the Republican majorities in both houses of Congress increased. Dollars and Ships Under the Federalists, the Republicans believed, the government had been needlessly extravagant…. The Jefferson administration moved deliberately to reverse the trend. In 1802, it persuaded Congress to abolish all internal taxes, leaving customs duties and the sale of western lands as the only source of revenue for the government. Meanwhile, Secretary of the Treasury [Albert] Gallatin drastically reduced government spending, cutting the already small staffs of the executive departments to minuscule levels. Although Jefferson was unable to retire the entire national debt as he had hoped, he did cut it almost in half (from $83 million to $45 million) during his presidency Jefferson also scaled down the armed forces. He reduced the tiny army of 4,000 men to 2,500. He cut the navy from twenty-five ships to seven and reduced the number of officers and sailors accordingly. Anything but the smallest of standing armies, he argued, might menace civil liberties and civilian control of government…. Conflict with the Courts Having won control of the executive and legislative branches of government, the Republicans looked with suspicion on the judiciary, which remained largely in the hands of Federalist judges. Soon after Jefferson’s first inauguration, his followers in Congress launched an attack on this last preserve of the opposition. Their first step was the repeal of the Judiciary Act of 1801, thus eliminating the judgeships to which Adams had made his “midnight appointments.”… [We will have much to say about these efforts in a future class.] DOUBLING THE NATIONAL DOMAIN Jefferson and Napoleon Jefferson was unaware at first of [French ruler] Napoleon’s imperial ambitions in America, and for a time he pursued a foreign policy that reflected his well-known admiration for France…. Jefferson began to reconsider his position toward France when he heard rumors of the secret transfer of Louisiana [from Spain to France]…. Always before, America had looked to France as its “natural friend.” But there was on the earth “one single spot” whose possessor was “our natural and habitual enemy.” That spot was New Orleans, the outlet through which the produce of the fast-growing western regions of the United STates traveled to the markets of the world. If France should actually seize New Orleans, Jefferson said, then “we must marry ourselves to the British fleet and nation.” Jefferson was even more alarmed when, in the fall of 1802, he learned that the [governor] at New Orleans…. had announced a disturbing new regulation. American ships sailing the Mississippi River had for many years been accustomed to depositing their cargoes in New Orleans for transfer to oceangoing vessels. The [governor] now forbade the practice… thus effectively closing the lower Mississippi to American shippers. Westerners demanded that the federal government do something to reopen the river…. Jefferson saw [a] solution. He instructed Robert Livingston, the American ambassador in Paris, to negotiate the purchase of New Orleans. Livingston on his own authority proposed that the French sell the United States the vast western part of Louisiana as well. In the meantime, Jefferson persuaded Congress to appropriate funds for an expansion of the army and the construction of a river fleet…. Perhaps that was why Napoleon suddenly decided to accept Livingston’s proposal and offer the United States the entire Louisiana territory. The Louisiana Purchase Faced with Napoleon’s startling proposal, Livingston and James Monroe, whom Jefferson had sent to Paris to assist in the negotiations, had to decide first whether they should even consider making a treaty for the purchase of the entire Louisiana Territory, since they had not been authorized by their government to do so. But fearful that Napoleon might withdraw the offer, they decided to proceed without further instructions from home…. By the terms of the treaty, the United States was to pay a total of 80 million francs ($15 million) to the French government…. In Washington, the president was both pleased and embarrassed when he received the treaty. He was pleased with the terms of the bargain but uncertain whether the United States had the authority to accept it, since he had always insisted that the federal government could rightfully exercise only those powers explicitly assigned to it. Nowhere did the Constitution say anything about the acquisition of new territory. But Jefferson’s advisers persuaded him that his treatymaking power under the Constitution would justify the purchase of Louisiana. The president finally agreed, trusting, as he said, “that the good sense of our country will correct the evil of loose construction when it shall produce ill effects.” The Republican Congress promptly approved the treaty and appropriated money to implement its provisions. Finally, late in 1803, the French [turned] the territory over to… the United States.