ORIGINAL INVESTIGATION

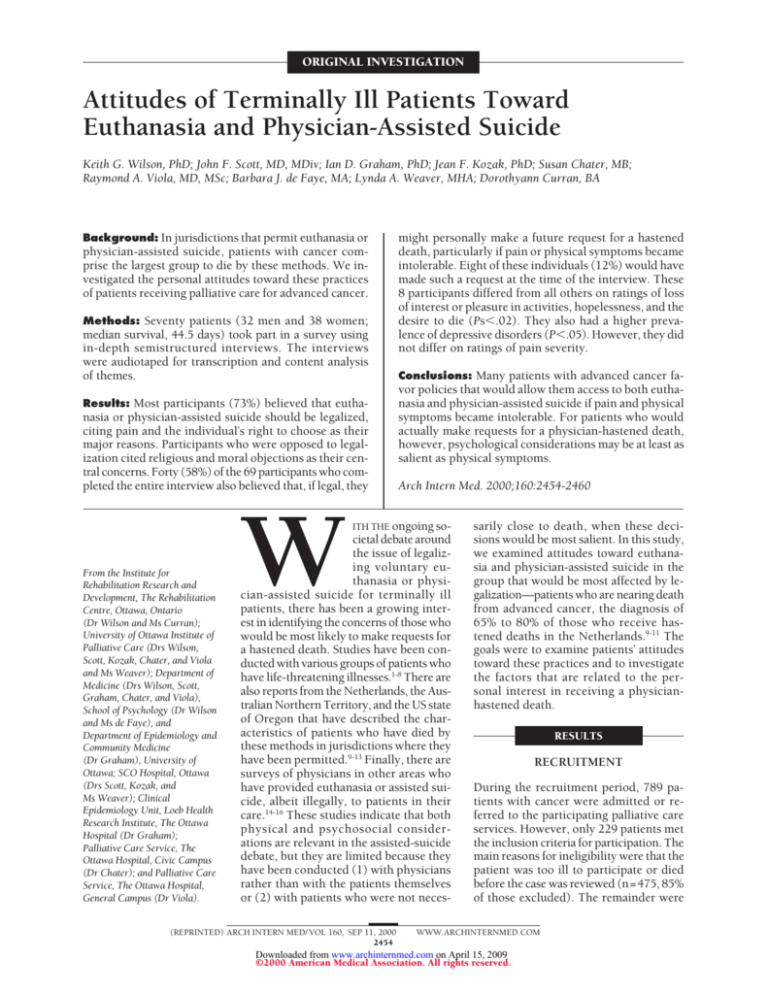

Attitudes of Terminally Ill Patients Toward

Euthanasia and Physician-Assisted Suicide

Keith G. Wilson, PhD; John F. Scott, MD, MDiv; Ian D. Graham, PhD; Jean F. Kozak, PhD; Susan Chater, MB;

Raymond A. Viola, MD, MSc; Barbara J. de Faye, MA; Lynda A. Weaver, MHA; Dorothyann Curran, BA

Background: In jurisdictions that permit euthanasia or

physician-assisted suicide, patients with cancer comprise the largest group to die by these methods. We investigated the personal attitudes toward these practices

of patients receiving palliative care for advanced cancer.

Methods: Seventy patients (32 men and 38 women;

median survival, 44.5 days) took part in a survey using

in-depth semistructured interviews. The interviews

were audiotaped for transcription and content analysis

of themes.

Results: Most participants (73%) believed that eutha-

nasia or physician-assisted suicide should be legalized,

citing pain and the individual’s right to choose as their

major reasons. Participants who were opposed to legalization cited religious and moral objections as their central concerns. Forty (58%) of the 69 participants who completed the entire interview also believed that, if legal, they

From the Institute for

Rehabilitation Research and

Development, The Rehabilitation

Centre, Ottawa, Ontario

(Dr Wilson and Ms Curran);

University of Ottawa Institute of

Palliative Care (Drs Wilson,

Scott, Kozak, Chater, and Viola

and Ms Weaver); Department of

Medicine (Drs Wilson, Scott,

Graham, Chater, and Viola),

School of Psychology (Dr Wilson

and Ms de Faye), and

Department of Epidemiology and

Community Medicine

(Dr Graham), University of

Ottawa; SCO Hospital, Ottawa

(Drs Scott, Kozak, and

Ms Weaver); Clinical

Epidemiology Unit, Loeb Health

Research Institute, The Ottawa

Hospital (Dr Graham);

Palliative Care Service, The

Ottawa Hospital, Civic Campus

(Dr Chater); and Palliative Care

Service, The Ottawa Hospital,

General Campus (Dr Viola).

W

might personally make a future request for a hastened

death, particularly if pain or physical symptoms became

intolerable. Eight of these individuals (12%) would have

made such a request at the time of the interview. These

8 participants differed from all others on ratings of loss

of interest or pleasure in activities, hopelessness, and the

desire to die (Ps,.02). They also had a higher prevalence of depressive disorders (P,.05). However, they did

not differ on ratings of pain severity.

Conclusions: Many patients with advanced cancer favor policies that would allow them access to both euthanasia and physician-assisted suicide if pain and physical

symptoms became intolerable. For patients who would

actually make requests for a physician-hastened death,

however, psychological considerations may be at least as

salient as physical symptoms.

Arch Intern Med. 2000;160:2454-2460

ITH THE ongoing so-

cietal debate around

the issue of legalizing voluntary euthanasia or physician-assisted suicide for terminally ill

patients, there has been a growing interest in identifying the concerns of those who

would be most likely to make requests for

a hastened death. Studies have been conducted with various groups of patients who

have life-threatening illnesses.1-8 There are

also reports from the Netherlands, the Australian Northern Territory, and the US state

of Oregon that have described the characteristics of patients who have died by

these methods in jurisdictions where they

have been permitted.9-13 Finally, there are

surveys of physicians in other areas who

have provided euthanasia or assisted suicide, albeit illegally, to patients in their

care.14-16 These studies indicate that both

physical and psychosocial considerations are relevant in the assisted-suicide

debate, but they are limited because they

have been conducted (1) with physicians

rather than with the patients themselves

or (2) with patients who were not neces-

(REPRINTED) ARCH INTERN MED/ VOL 160, SEP 11, 2000

2454

sarily close to death, when these decisions would be most salient. In this study,

we examined attitudes toward euthanasia and physician-assisted suicide in the

group that would be most affected by legalization—patients who are nearing death

from advanced cancer, the diagnosis of

65% to 80% of those who receive hastened deaths in the Netherlands.9-11 The

goals were to examine patients’ attitudes

toward these practices and to investigate

the factors that are related to the personal interest in receiving a physicianhastened death.

RESULTS

RECRUITMENT

During the recruitment period, 789 patients with cancer were admitted or referred to the participating palliative care

services. However, only 229 patients met

the inclusion criteria for participation. The

main reasons for ineligibility were that the

patient was too ill to participate or died

before the case was reviewed (n=475, 85%

of those excluded). The remainder were

WWW.ARCHINTERNMED.COM

Downloaded from www.archinternmed.com on April 15, 2009

©2000 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

PARTICIPANTS AND METHODS

RECRUITMENT

The survey was conducted from 1996 to 1998. The participants were patients admitted to a regional palliative care

inpatient unit or patients who received palliative care consultation services on the oncology wards of 2 Canadian tertiary care hospitals. The study protocol was approved by

the ethics review committees of all the participating institutions.

At each site, the clinical palliative care teams reviewed consecutive referrals or admissions for the following inclusion criteria: (1) in the team’s opinion, the patient was medically and cognitively able to participate; (2)

the patient had been informed that the malignant illness

was incurable; and (3) the palliative care team was confident that broaching a discussion of euthanasia and physician-assisted suicide would not undermine their clinical role

with the patient. If the patient agreed, a meeting was arranged with a research interviewer, who obtained written

informed consent.

PROCEDURE

The semistructured interviews were conducted by a clinical psychologist, doctoral students in psychology, or a research associate in palliative care. All interviews were attended by both a primary interviewer and an observer, to

permit the evaluation of interrater reliability. They were also

audiotaped for later transcription.

The interview first addressed the subject’s general attitudes toward the acceptability and legal status of both euthanasia and physician-assisted suicide. Euthanasia was defined as an action in which “a medical doctor gives an

overdose of medication to purposely end a patient’s life.

This is only done with patients who have asked their doctor to help them die in this way. Usually, the patients involved are very ill with a life-threatening disease.” Physicianassisted suicide was defined as an action in which “a medical

doctor provides drugs and advice, so that a patient could

commit suicide. The doctor does not actually inject the

drugs, but rather gives the patient the means to end his or

her own life.” The subject was then asked whether each of

these practices is acceptable, whether they should be legalized, and whether there are any important differences

between them.

The interview then moved on to review the subject’s personal circumstances, beginning with an inquiry into physical symptoms of pain, drowsiness, weakness, nausea, and

breathlessness, which are among the most prevalent problems in the final weeks of life.17-19 The protocol also addressed specific end-of-life concerns that have been relevant

in previous studies of euthanasia or assisted suicide in

medical populations, including the loss of control, loss of dignity, sense of being a burden to others, and hopelessness.7,9,20 Next, the interview addressed the mental health issues of anxiety, depression, and loss of interest or pleasure

in activities. This section then concluded with an inquiry into

the subject’s desire for death.21

Each of these 13 symptoms and concerns was

assessed using interview items that began with a structured lead question, followed by a series of follow-up

prompts to clarify the severity of the problem. Severity was

then rated by the interviewer on a 7-point scale (none,

minimal, mild, moderate, strong, severe, and extreme).

The screening items for anxiety, depression, and loss of

interest or pleasure were used in conjunction with the Primary Care Evaluation for Mental Disorders (PRIME-MD)22

to permit the full diagnostic assessment of discrete anxiety

and depressive syndromes, as defined by the Diagnostic

and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition

(DSM-IV).23-25

The last section of the interview returned to the topics of euthanasia and physician-assisted suicide, with a focus on the subject’s personal situation. Specifically, the subject was asked (1) whether he or she would have asked for

euthanasia or assisted suicide, if they were legal and available, at any point in the current illness; (2) if there were

any foreseeable circumstances in which he or she would

make such a request in the future, and; (3) whether he or

she would actually initiate a request now, in the current

circumstances.

DATA ANALYSIS

The audiotaped responses were transcribed verbatim to facilitate content analysis.26,27 This is an inductive strategy

that involves the process of breaking down, constantly comparing and categorizing narrative information, resulting in

the identification of underlying themes. All transcripts were

reviewed independently by 3 investigators (K.G.W., I.D.G.,

and J.F.K.), who then met as a team to reach consensus on

themes. Categories of response that were provided by more

than 5% of the total study group (at least 4 participants)

are reported.

For the 13 clinical rating scales, the intraclass correlations between the 2 raters exceeded r= 0.92 in each case.

In the diagnosis of mental disorders, there was only 1 disagreement (k= 0.96), confirming that the assessments had

high interrater reliability.

For the quantitative analyses, we identified subgroups of subjects who differed with respect to their personal interest in receiving a physician-hastened death. The

demographic and clinical characteristics of these subgroups were compared statistically using x2 and Fisher exact tests for categorical data, and analyses of variance for

continuous measures and rating scales. Significant F tests

were followed up with Tukey pairwise comparisons.

excluded because of language barriers (n=35, 6%), a clinical decision that it would be inappropriate to approach

the patient about this topic (n=21, 4%), discharge within

24 hours (n=18, 3%), or objection by the patient’s family or attending physician (n = 11, 2%). Of the 229 patients who were initially considered to be eligible, 79

(34%) were not approached because they either deterio(REPRINTED) ARCH INTERN MED/ VOL 160, SEP 11, 2000

2455

rated medically or were discharged before the required

consents were obtained.

In total, the possibility of participation was raised

initially with 150 patients, 80 of whom declined. Thus,

the 70 participants who took part in the study represent

47% of the patients who were finally approached, and

9% of all patients with cancer who received palliative care

WWW.ARCHINTERNMED.COM

Downloaded from www.archinternmed.com on April 15, 2009

©2000 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

Table 1. Demographic and Clinical Characteristics

Age, mean (SD), y

Sex, M/F

Married, No. (%)

Education, No. (%)

Less than high school

High school

More than high school

Religion, No. (%)

Roman Catholic

Protestant

None

Other

Primary tumor site, No. (%)

Lung

Genitourinary

Female breast

Gastrointestinal

Head and neck

Other

Unknown

Survival duration, median (range), d

Medications, No. (%)

Opioids

Antidepressants

Anxiolytics

Mental disorders, No. (%)

Depression

Anxiety

Any disorder

.1 Disorder

64.5 (12.1)

32/38

34 (49)

21 (30)

17 (24)

32 (46)

29 (41)

29 (41)

7 (10)

5 (7)

15 (21)

13 (19)

9 (13)

9 (13)

7 (10)

11 (16)

6 (9)

44.5 (1-183)

55 (79)

17 (24)

19 (27)

14 (20)

7 (10)

16 (23)

6 (9)

services on the participating units during the study period. Limited data about age and sex were available for

patients who declined participation. There were no differences in these characteristics between the patients who

did and did not participate (Ps..10).

One participant completed a partial interview before requesting a break, but was not able to complete the

full protocol because of progressive illness. The partial

data from this person have been included where they are

available.

PARTICIPANTS

The demographic characteristics of the 70 participants

(32 men and 38 women) are shown in Table 1. Their

average age was 64.5 years (range, 43-88 years). In general, the study group was highly educated, with 49 participants (70%) having at least a high school education.

From the date of the interview, the median survival duration of the study group was 44.5 days, with only 11

participants (16%) living as long as 6 months.

ATTITUDES TOWARD THE ACCEPTABILITY

AND LEGAL STATUS OF EUTHANASIA

AND ASSISTED SUICIDE

Forty-five participants (64%) considered that both euthanasia and physician-assisted suicide are acceptable

practices that should be legalized, whereas 15 (21%) reported that both are unacceptable and should not be legalized. Of the remaining 10 participants (14%), 3 were

(REPRINTED) ARCH INTERN MED/ VOL 160, SEP 11, 2000

2456

Table 2. Reasons for or Against Legalization of

Euthanasia and Physician-Assisted Suicide*

For Legalization (n = 51)

Individual’s right to choose

Pain

Diminished quality of life

Suffering

Hopeless situation

Mental symptoms

Burden for others

Physical symptoms (other than pain)

Knowledge of others’ experience

Against Legalization (n = 16)

Religious/spiritual beliefs

Secular moral values

Potential for abuse

Inappropriate role for physicians

Concerns about stability and rationality

22 (43)

22 (43)

18 (35)

12 (24)

12 (24)

9 (18)

7 (14)

5 (10)

4 (8)

8 (50)

6 (38)

5 (31)

5 (31)

4 (25)

*Data are given as number (percentage) of participants citing each reason.

Only reasons mentioned by at least 4 participants are presented.

uncertain, 4 reported that only euthanasia should be legalized, 1 reported that both practices are acceptable in

an informal way but should not be legalized, and 2 indicated that both are unacceptable in principle but should

be legalized anyway if they are going to be practiced surreptitiously.

The 51 participants who were in favor of at least limited legal access to either euthanasia or assisted suicide

provided a total of 122 individual reasons to support their

opinion. These reasons are summarized in Table 2. In

general, they believed that people have the right to decide how they will die. Other frequent reasons referred

to uncontrollable pain, diminished quality of life, and

other types of suffering, both physical and mental. Some

participants also expressed a concern about relieving the

burden on family members, and some noted that their

attitudes were influenced by their knowledge of the endof-life experiences of others.

The 16 participants who were against legalization

provided 36 individual reasons for their view, consisting mostly of opposition because of religious or spiritual beliefs, or because of secular moral values. They also

raised concerns about the potential for abuse, that causing death is not an appropriate role for physicians, and

that the desire to die is not always stable or rational.

PERCEIVED DIFFERENCES BETWEEN

EUTHANASIA AND ASSISTED SUICIDE

Participants were also asked whether there are any

important differences between euthanasia and assisted

suicide. Twenty-one participants (30%) reported that they

did see important distinctions between the practices; 14

(67%) found euthanasia to be more acceptable and 7

(33%) believed that physician-assisted suicide is more

acceptable.

The participants who found euthanasia to be more

acceptable than assisted suicide provided a total of 23 reasons for their view, including the argument that terminating life requires technical medical knowledge (n=10,

WWW.ARCHINTERNMED.COM

Downloaded from www.archinternmed.com on April 15, 2009

©2000 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

71%), and that physicians are best able to assess the appropriate timing, stability, and rationality of the request

(n=6, 43%).

Those who considered physician-assisted suicide to

be more acceptable provided a total of 11 reasons, including the concern that the direct termination of life is

not an appropriate role for physicians (n = 5, 71%), and

that assisted suicide maximizes choice and control for

the patient (n= 5, 71%).

PERSONAL INTEREST IN RECEIVING

EUTHANASIA OR ASSISTED SUICIDE

When asked whether they could envision future circumstances in which they would personally request euthanasia or assisted suicide, 32 participants (46%) reported

that they could, 19 (28%) reported that they could not,

and 10 (14%) were uncertain. Of those with a possible

interest for the future, 3 participants believed that they

would already have made requests at earlier points in

their illness, but they no longer thought that way by the

time of the interview. In addition, however, there were

also 8 other patients, or 12% of the entire study group,

who reported that they would request euthanasia or

assisted suicide immediately, in their current circumstances.

REASONS FOR WANTING EUTHANASIA

OR ASSISTED SUICIDE IN THE FUTURE

The 32 participants who indicated a possible future interest in receiving euthanasia or assisted suicide reported a total of 63 reasons for why they would make

such requests. The most frequent reasons focused on the

physical distress associated with uncontrollable pain

(n=15, 47%) and other severe physical symptoms (n=11,

34%). Some participants also mentioned nonphysical circumstances that would motivate them to make a request, including if their global quality of life deteriorated (n=8, 25%), if they became a burden to others (n=7,

22%), if they were generally suffering (n=6, 19%), if they

developed mental symptoms (n = 6, 19%), if they believed that they were simply lingering while waiting to

die (n=5, 16%), or if they perceived their overall situation as hopeless (n = 4, 13%).

Twenty-two (69%) of these participants reported a

preference for a particular method of hastened death, with

the majority (n= 16) preferring euthanasia over assisted

suicide (n=6) (P = .03).

PATIENTS WHO WOULD REQUEST A HASTENED

DEATH IN THEIR CURRENT CIRCUMSTANCES

The 8 participants who currently desired a physicianhastened death comprised 5 men and 3 women, aged 47

to 82 years. Three were married, 3 were divorced, and 2

were widowed. Three were university graduates, 3 had

completed high school, and 2 had less than high school

educations. Three were from the Roman Catholic faith,

3 were from Protestant backgrounds, and 2 reported no

religious affiliation. The DSM-IV diagnoses within this

group included 4 patients with major depression, 2 of

(REPRINTED) ARCH INTERN MED/ VOL 160, SEP 11, 2000

2457

whom had comorbid anxiety disorders, and 1 with major depression in partial remission.

When asked about the method that they would

choose to end their lives, 4 participants indicated a preference for euthanasia, 2 for physician-assisted suicide,

and 2 had no preference. As a group, they provided a total of 48 individual statements that clarified why they were

ready to end their lives. In general, they recognized that

their illness was terminal (n=4, 50%; eg, “For two months

I have known that it was over for me.” “I have a terminal disease. I’m not going to get better.”), and they believed that they had achieved some degree of acceptance that they were going to die (n=4, 50%; eg, “I’m in

a position now in my life where I want to go.” “I’d like

to make my peace and go.”). They spoke of suffering (n=4,

50%; eg, “The family won’t suffer and I won’t suffer.” “If

suffering is inevitable, they [the patient] should have a

say.”) and of a diminished quality of life (n=4, 50%; eg,

“If a patient feels he can no longer function and is no more

a human being.” “God put us here to enjoy life. He didn’t

cause my illness but, I mean, I’m deteriorating and that’s

that.”). They believed that they had the right to exercise

choice and control over the manner of their deaths (n=6,

75%; eg, “I think I should have control over dying in dignity. “Nobody should be forced to stay alive by other

people.”) and that euthanasia or assisted suicide would

provide an easier means of dying than they were actually experiencing (n=5, 63%; eg, “You only have to press

a button to finish it and sleep peacefully.” “Just to expire in my sleep would be the perfect way for me.”). Pain

was cited as a contributing reason by 1 person, although

a fear of pain was discussed by another, and adverse reactions to narcotic analgesics were reported by a third.

Four of the 8 participants died within 2 weeks of

the interview, and 3 others died over the next 1 to 4

months. The last patient rallied medically during the admission, and lived for another 20 months.

CLINICAL CORRELATES

Statistical comparisons were conducted between 3 groups:

(1) those who would never consider euthanasia or assisted suicide (n=19); (2) those who would consider it

in the future, but who had no current interest (n=32);

and (3) those who would make requests in their current

circumstances (n=8) (Table 3).

The 3 groups did not differ on any demographic characteristic (Ps..10). Similarly, they did not differ with respect to the level of pain that they experienced, or in the

subjective sense of depressed mood (Ps..10). However, there were a number of differences between groups

in the severity of other symptoms and concerns, including drowsiness (P =.02), weakness (P =.04), loss of control (P = .04), loss of interest or pleasure in activities

(P=.007), hopelessness (P,.001), and desire for death

(P,.001).

In post hoc comparisons, participants with no interest in receiving a hastened death and those with only

a hypothetical future interest did not differ on any measure (Ps..05). Rather, the 8 participants with a current

interest accounted for all of the significant findings. They

reported greater loss of interest or pleasure in activities,

WWW.ARCHINTERNMED.COM

Downloaded from www.archinternmed.com on April 15, 2009

©2000 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

Table 3. Interviewer Severity Ratings

of Symptoms and Concerns*

Symptom

or Concern

No Interest†

(n = 19)

Future Interest

(n = 32)

Current Interest

(n = 8)

Pain

Drowsiness‡

Nausea

Weakness‡

Breathlessness

Loss of control‡

Loss of dignity

Sense of burden

Hopelessness§

Anxiety

Depression

Loss of interest§

Desire for death§

2.32 (1.57)

1.79 (1.44)

1.16 (1.74)

2.68 (1.57)

1.42 (1.92)

0.79 (1.08)

0.74 (0.93)

2.26 (1.37)

0.74 (0.99)

0.95 (1.42)

0.84 (0.90)

0.95 (1.03)

1.68 (0.70)

1.56 (1.48)

2.44 (1.54)

0.82 (1.38)

3.09 (1.57)

1.66 (1.75)

1.31 (1.87)

0.91 (1.55)

2.00 (1.59)

0.69 (1.09)

1.03 (1.20)

1.00 (1.08)

1.00 (1.72)

2.03 (1.27)

2.25 (0.89)

3.63 (1.85)

1.38 (1.41)

4.38 (1.06)

2.50 (1.60)

2.63 (2.26)

1.50 (2.33)

2.13 (2.23)

2.88 (2.36)

1.75 (1.67)

1.75 (1.67)

3.00 (2.20)

5.00 (1.66)

*Data are given as mean (SD) values derived from 7-point rating scales

where 0 = none, 1 = minimal, 2 = mild, 3 = moderate, 4 = strong, 5 = severe,

and 6 = extreme.

†No interest refers to participants who report no interest in ever

requesting a death hastened by euthanasia or physician-assisted suicide;

future interest comprises participants who could foresee making a request in

the future, but who would not do so in their current circumstances; current

interest refers to participants who would make a request for a hastened

death in their current circumstances.

‡Participants with a current interest differ from those with no interest at

P,.05.

§Participants with a current interest differ from both other groups at

P,.05.

hopelessness, and desire for death than did participants

in both other groups (Ps,.02). They also reported greater

drowsiness, weakness, and loss of control than did participants with no interest (Ps,.04).

In addition, 5 (63%) of the 8 individuals with a current interest in euthanasia or assisted suicide met diagnostic criteria for a mental disorder, compared with 3

(16%) of 19 with no interest (P = .03) and 7 (22%) of 32

with only a possible interest for the future (P =.04).

COMMENT

Despite widespread interest in the issues of euthanasia

and physician-assisted suicide for people who are terminally ill, this study is the first to have directly examined

the attitudes of patients who are nearing death from advanced cancer. Although it would have been preferable

to have achieved a higher response rate than 47% of patients approached, the difficulties of recruitment in the

palliative care setting are well known.28,29 It is also important to note that most of the participants in the present study were gravely ill, the protocol was quite rigorous, and the topic is controversial. We suspect that these

are the major reasons for the observed rate of refusal. Nevertheless, it must be acknowledged that the patients who

chose not to take part in the study may have differed in

important ways from those who did.

With this proviso, our findings agree with those of

others who have reported that the majority of patients

with life-threatening illnesses support the general principle of legalizing euthanasia or physician-assisted suicide.3-6 The qualitative aspects of the protocol also shed

light on the reasons that underlie patient preferences. It

(REPRINTED) ARCH INTERN MED/ VOL 160, SEP 11, 2000

2458

is apparent from these reasons that people with different opinions about legalization are not simply arguing

for different sides of the same issue; rather, their positions are grounded in different issues altogether. People

who are against legalization are motivated primarily by

religious or secular moral concerns, which place the sanctity of human life above other considerations. Those who

are in favor of legalization are more concerned about the

relief of uncontrollable pain and suffering, as well as with

the rights of the individual to exercise choice and control. These are fundamental differences in the premises

on which the 2 positions are based, which suggests that

there is little common ground between them on which

to reach a compromise solution.

In the United States, the movement toward legalization has focused mostly on the specific issue of assisted suicide, as reflected in the Oregon Death With Dignity legislation. Nevertheless, many right-to-die activists

have acknowledged that their long-term goal includes access to euthanasia as well.30 The pro-legalization participants in the present study clearly saw euthanasia as being at least as acceptable as assisted suicide. Among those

who would personally consider requesting a hastened

death, euthanasia would actually have been the more common choice. This finding parallels the experience of the

Netherlands, where euthanasia takes place much more

frequently than assisted suicide.9-11 The arguments in favor of assisted suicide include concerns about patient autonomy and control, the moral limits of medical intervention, the potential for error or abuse, and the possibility

of greater legal safeguards for physicians.31,32 Patient preferences have seldom been cited as a relevant factor in this

debate. Indeed it can be argued that patient preferences

are not relevant if they point to a position that is immoral and unethical.33 At the empirical level, however,

it is apparent that many terminally ill patients see a role

for euthanasia. This is largely because they view the termination of life as requiring an advanced technical knowledge of medicine.

Almost half of the participants could imagine future circumstances in which they would personally ask

for assistance in hastening their own deaths. The most

common circumstances involved scenarios of uncontrolled pain and physical symptoms. For these individuals, there might be some comfort in knowing that euthanasia or assisted suicide were available, in the event that

their worst fears about pain and symptoms indeed came

true.34,35 These desperate situations remain hypothetical

future events for this group, however, and in the meanwhile they are doing their best to carry on. Apart from

their accepting attitude toward euthanasia and assisted

suicide, their clinical profiles appear to be quite similar

to those of patients who would never request a hastened

death.

On the other hand, the 8 participants who would

have made requests for euthanasia or assisted suicide in

their current circumstances appear to be quite different

from the others who took part in this study, and they illustrate some of the key issues that have emerged in the

legalization debate.

First, it is not always a straightforward task to specify

when a life-threatening illness has entered a terminal

WWW.ARCHINTERNMED.COM

Downloaded from www.archinternmed.com on April 15, 2009

©2000 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

phase.13 One person who would have requested a physician-hastened death was admitted to the palliative care

unit, but improved, was discharged, and survived for another 20 months. Second, the desire to die is not necessarily stable over time.21,36 Three other participants reported that they would have requested a hastened death

at earlier points in their illness, but they would no longer

have done so by the time of the interview.

Third, the current desire for a physician-hastened

death was associated with a high prevalence of depressive disorders. This is significant in the present context

because depression is a potentially treatable problem,

which in severe cases may bias health decisions in a negative way.37 The clinical diagnoses of depression did not

always arise from reports of a greater subjective sense of

depressed mood, however, and none of the participants

explicitly mentioned depression as the reason for wanting to die. Rather, the diagnoses were sometimes based

in the report of a pervasive loss of interest or pleasure in

activities, which is also a core criterion symptom of depressive disorders.23 When coupled with a sense of hopelessness and loss of control, which were also elevated

among these individuals, then euthanasia and physicianassisted suicide may be seen as offering the relief of an

easier death.

Fourth, of the physical symptoms that we examined, weakness and drowsiness showed the strongest association with the desire for a hastened death. It is not

clear whether these symptoms directly cause the desire

to die, or whether they arise because of other factors, such

as a higher use of sedating medications in the treatment

of this distressed group, more advanced physical disease and nearness to death, or whether they emerge as

part of the symptom complex of depression in the medically ill. It is noteworthy, however, that pain, although

common at low levels in the majority of participants, did

not differ significantly between the groups. Among the

general public, support for legalization is highest in scenarios that involve terminally ill patients who have

uncontrollable pain.3 Public support is lower in scenarios that involve patients who have adequate pain

control, but who want to die because of physical debility

or a perceived loss of purpose and meaning.3 In reality,

patients in the latter circumstances may be more characteristic of those who would actually make requests for

hastened death. Therefore, if legalization is to be

reviewed on a more widespread basis, the public debate

should be broadened to include a discussion of the

acceptability of these factors as reasons to provide euthanasia or assisted suicide.

Finally, it must also be noted that all of the participants in this Canadian study had access to state-funded

palliative care services, at no personal financial cost. Unfortunately, this is not the case for every person who is

facing death. The lack of accessible palliative care is a compelling argument for prudence in the review of prohibitions against euthanasia and physician-assisted suicide.38,39 We also have much to learn about patients’

perceptions of quality end-of-life care, and how to provide it.40 Nevertheless, even with good care, it is evident

that there will still be patients who would prefer to end

their lives through direct physician intervention.41 Our

(REPRINTED) ARCH INTERN MED/ VOL 160, SEP 11, 2000

2459

results indicate that it is not necessarily extreme physical distress that motivates this desire. Rather, the psychological and existential dimensions of suffering—

which are, perhaps, no less central in determining quality

of life—also emerge as important reasons behind patient requests for physician-hastened death.

Accepted for publication March 8, 2000.

The research was supported by grant 6606-6475002 from the National Health Research and Development

Program (NHRDP) of Health Canada, and by a Career

Scientist award from the Ontario Ministry of Health (Dr

Graham).

The views expressed herein are those of the authors,

and do not necessarily reflect those of the NHRDP, Health

Canada, or the Ontario Ministry of Health.

We acknowledge the contributions of Cathe Boucher,

RN, Maryse Bouvette, MEd, RN, Michael Claessens, MD,

Pippa Hall, MD, MEd, Virginia Jarvis, BScN, RN, Liliane

Locke, BScN, RN, and Judi Paterson, MA, RN, who

assisted with the recruitment of participants; Julie Allston,

MSc, Anne-Marie Baronet, BA, Mariette Blouin, BA, Lori

deLaplante, BA, and Amanda Pontefract, MSc, who served

as interviewers; Maureen Ferrante, BSc, RN, who helped

with data collection; Suzanne Pelletier, who transcribed

the interviews and helped with report preparation; Paul

Hébert, MD, MHSc, who reviewed an earlier draft of the

manuscript, and Jay Lynch, BAdm, RN, who assisted with

the dissemination of results. We also thank the people who

participated in the study. Despite their failing health, they

gave their time generously to this project.

Reprints: Keith G. Wilson, PhD, Institute for Rehabilitation Research and Development, The Rehabilitation

Centre, 505 Smyth Rd, Ottawa, Ontario, Canada K1H

8M2.

REFERENCES

1. Owen C, Tennant C, Levi J, Jones M. Suicide and euthanasia: patient attitudes in

the context of cancer. Psychooncology. 1992;1:79-88.

2. Owen C, Tennant C, Levi J, Jones M. Cancer patients’ attitudes to final events in

life: wish for death, attitudes to cessation of treatment, suicide and euthanasia.

Psychooncology. 1994;3:1-9.

3. Emanuel EJ, Fairclough DL, Daniels ER, Clarridge BR. Euthanasia and physicianassisted suicide: attitudes and experiences of oncology patients, oncologists, and

the public. Lancet. 1996;347:1805-1810.

4. Suarez-Almazor ME, Belzile M, Bruera E. Euthanasia and physician-assisted suicide: a comparative survey of physicians, terminally ill cancer patients and the

general population. J Clin Oncol. 1997;15:418-427.

5. Sullivan M, Rapp S, Fitzgibbon D, Chapman CR. Pain and the choice to hasten

death in patients with painful metastatic cancer. J Palliat Care. 1997;13:18-28.

6. Breitbart W, Rosenfeld BD, Passik SD. Interest in physician-assisted suicide among

ambulatory HIV-infected patients. Am J Psychiatry. 1996;153:238-242.

7. Ganzini L, Johnston WS, McFarland BH, Tolle SW, Lee MA. Attitudes of patients

with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis and their care givers toward assisted suicide.

N Engl J Med. 1998;339:967-973.

8. Berkman CS, Cavallo PF, Chesnut WC, Holland NJ. Attitudes toward physicianassisted suicide among persons with multiple sclerosis. J Palliat Med. 1999;2:

51-63.

9. van der Maas PJ, van Delden JJM, Pijnenborg L, Looman CWN. Euthanasia

and other medical decisions concerning the end of life. Lancet. 1991;338:669674.

10. van der Maas PJ, van der Wal G, Haverkate I, et al. Euthanasia, physicianassisted suicide, and other medical practices involving the end of life in the Netherlands, 1990-1995. N Engl J Med. 1996;335:1699-1705.

11. Onwuteaka-Philipsen BD, Muller MT, van der Wal G, Van Eijk JTM, Ribbe MW.

WWW.ARCHINTERNMED.COM

Downloaded from www.archinternmed.com on April 15, 2009

©2000 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

12.

13.

14.

15.

16.

17.

18.

19.

20.

21.

22.

23.

24.

Active voluntary euthanasia or physician-assisted suicide? J Am Geriatr Soc. 1997;

45:1208-1213.

Chin AE, Hedberg K, Higginson GK, Fleming DW. Legalized physician-assisted

suicide in Oregon—the first year’s experience. N Engl J Med. 1999;340:577583.

Kissane DW, Street A, Nitschke P. Seven deaths in Darwin: case studies under

the Rights of the Terminally Ill Act, Northern Territory, Australia. Lancet. 1998;

352:1097-1102.

Back AL, Alcser KH, Doukas DJ, Lichtenstein RL, Corning AD, Brody H. Attitudes of Michigan physicians and the public toward legalizing physicianassisted suicide and voluntary euthanasia. N Engl J Med. 1996;334:303-309.

Meier DE, Emmons C-A, Wallenstein S, Quitt T, Morrison RS, Cassel CK. A national survey of physician-assisted suicide and euthanasia in the United States.

N Engl J Med. 1998;338:1193-201.

Emanuel EJ, Daniels ER, Fairclough DL, Clarridge BR. The practice of euthanasia and physician-assisted suicide in the United States: adherence to proposed

safeguards and effects on physicians. JAMA. 1998;280:507-513.

Coyle N, Adelhardt J, Foley KM, Portenoy RK. Character of terminal illness in the

advanced cancer patient: pain and other symptoms during the last four weeks of

life. J Pain Symptom Manage. 1990;5:83-93.

Curtis EB, Krech R, Walsh TD. Common symptoms in patients with advanced

cancer. J Palliat Care. 1991;7:25-29.

Vertafridda Y, Ripamonti C, DeConno F, Tamburini M, Cassileth BR. Symptom

prevalence and control during cancer patients’ last day of life. J Palliat Care. 1990;

6:7-11.

Chochinov HM, Wilson KG, Enns M, Lander S. Depression, hopelessness, and

suicidal ideation in the terminally ill. Psychosomatics. 1998;39:366-370.

Chochinov HM, Wilson KG, Enns M, et al. Desire for death in the terminally ill.

Am J Psychiatry. 1995;152:1185-1191.

Spitzer RL, Williams JBW, Kroenke K, et al. Utility of a new procedure for diagnosing mental disorders in primary care: the PRIME-MD 1000 Study. JAMA. 1994;

272:1749-1756.

American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental

Disorders, Fourth Edition. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association;

1994.

Chochinov HM, Wilson KG, Enns M, Lander S. Prevalence of depression in the

terminally ill: effects of diagnostic criteria and symptom threshold judgements.

Am J Psychiatry. 1994;151:537-540.

(REPRINTED) ARCH INTERN MED/ VOL 160, SEP 11, 2000

2460

25. Wilson KG, Chochinov HM, deFaye BJ. Diagnosis and management of depression

in palliative care. In: Chochinov HM, Breitbart W, eds. Handbook of Psychiatry in

Palliative Medicine. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2000:25-49.

26. Crabtree B, Miller M. Doing Qualitative Research: Research Methods for Primary Care. Newbury Park, Calif: Sage; 1992.

27. Altheide D. Ethnographic content analysis. Qualitative Sociol. 1987;10:65-77.

28. McWhinney IR, Bass MJ, Donner A. Evaluation of a palliative care service: problems and pitfalls. BMJ. 1994;309:1340-1342.

29. Calman K, Hanks G. Clinical and health services research. In: Doyle D, Hanks

GWC, MacDonald N, eds. Oxford Textbook of Palliative Medicine. 2nd ed. New

York, NY: Oxford University Press; 1998:159-165.

30. Annas GJ. Death by prescription: the Oregon initiative. N Engl J Med. 1994;331:

1240-1243.

31. Battin MP. Euthanasia: the way we do it, the way they do it. J Pain Symptom

Manage. 1991;6:298-305.

32. Quill TE, Cassel CK, Meir DE. Care of the hopelessly ill: proposed clinical criteria

for physician-assisted suicide. N Engl J Med. 1992;327:1380-1384.

33. Pellegrino ED. The limitation of empirical research in ethics. J Clin Ethics. 1995;

6:161-162.

34. Wilson KG, Viola RA, Scott JF, Chater S. Talking to the terminally ill about euthanasia and physician-assisted suicide. Can J Clin Med. 1998;5:68-74.

35. Breitbart W, Chochinov HM, Passik S. Psychiatric aspects of palliative care. In:

Doyle D, Hanks GWC, MacDonald N, eds. Oxford Textbook of Palliative Medicine. 2nd ed. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 1998:933-954.

36. Chochinov HM, Tataryn D, Clinch JJ, Dudgeon D. Will to live in the terminally ill.

Lancet. 1999;354:816-819.

37. Ganzini L, Lee MA, Heintz RT, Bloom JD, Fenn DS. The effect of depression treatment on elderly patients’ preferences for life-sustaining medical therapy. Am J

Psychiatry. 1994;151:1631-1636.

38. Latimer EJ, McGregor J. Euthanasia, physician-assisted suicide and the ethical

care of dying patients. CMAJ. 1994;151:1133-1136.

39. Foley KM. The relationship of pain and symptom management to patient requests for physician-assisted suicide. J Pain Symptom Manage. 1991;6:289297.

40. Singer PA, Martin DK, Kelner M. Quality end-of-life care: patients’ perspectives.

JAMA. 1999;281:163-168.

41. Seale C, Addington-Hall J. Euthanasia: the role of good care. Soc Sci Med. 1994;

39:647-654.

WWW.ARCHINTERNMED.COM

Downloaded from www.archinternmed.com on April 15, 2009

©2000 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.