An Attributional Theory of Achievement Motivation and Emotion

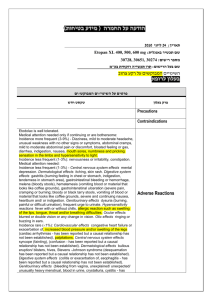

advertisement