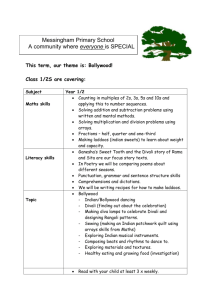

Go West: The Growth of Bollywood

advertisement