Financial Fraud Litigation

advertisement

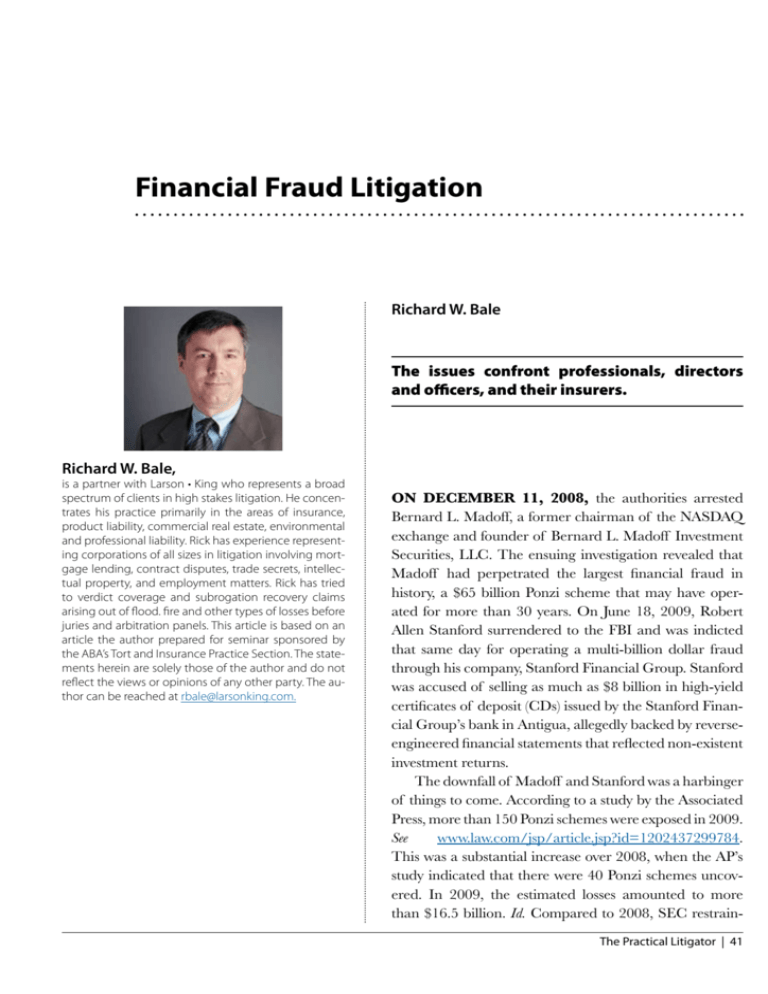

Financial Fraud Litigation Richard W. Bale The issues confront professionals, directors and officers, and their insurers. Richard W. Bale, is a partner with Larson • King who represents a broad spectrum of clients in high stakes litigation. He concentrates his practice primarily in the areas of insurance, product liability, commercial real estate, environmental and professional liability. Rick has experience representing corporations of all sizes in litigation involving mortgage lending, contract disputes, trade secrets, intellectual property, and employment matters. Rick has tried to verdict coverage and subrogation recovery claims arising out of flood. fire and other types of losses before juries and arbitration panels. This article is based on an article the author prepared for seminar sponsored by the ABA’s Tort and Insurance Practice Section. The statements herein are solely those of the author and do not reflect the views or opinions of any other party. The author can be reached at rbale@larsonking.com. On December 11, 2008, the authorities arrested Bernard L. Madoff, a former chairman of the NASDAQ exchange and founder of Bernard L. Madoff Investment Securities, LLC. The ensuing investigation revealed that Madoff had perpetrated the largest financial fraud in history, a $65 billion Ponzi scheme that may have operated for more than 30 years. On June 18, 2009, Robert Allen Stanford surrendered to the FBI and was indicted that same day for operating a multi-billion dollar fraud through his company, Stanford Financial Group. Stanford was accused of selling as much as $8 billion in high-yield certificates of deposit (CDs) issued by the Stanford Financial Group’s bank in Antigua, allegedly backed by reverseengineered financial statements that reflected non-existent investment returns. The downfall of Madoff and Stanford was a harbinger of things to come. According to a study by the Associated Press, more than 150 Ponzi schemes were exposed in 2009. See www.law.com/jsp/article.jsp?id=1202437299784. This was a substantial increase over 2008, when the AP’s study indicated that there were 40 Ponzi schemes uncovered. In 2009, the estimated losses amounted to more than $16.5 billion. Id. Compared to 2008, SEC restrainThe Practical Litigator | 41 42 | The Practical Litigator ing orders against Ponzi scheme operators were up 82 percent and Commodity Futures Trading Commission civil filings against Ponzi schemes doubled in 2009. Id. The Madoff investor and feeder fund litigation includes at least 19 federal securities class actions, over 50 lawsuits filed in state court, and eight insurance coverage cases, according to a list maintained by Kevin LaCroix’s D&O Diary Web site. See, Madoff Investor and Feeder Fund Litigation: The List, available at www.dandodiary.com. An early 2009 estimate by Aon Benfield’s Actuarial and Enterprise Risk Management practice predicted $1.8 billion in direct insurance payouts on behalf of feeder funds, banks and other investment firms for Madoff-related liabilities, although payouts could go as high as $3.8 billion. See, Aon Benfield Forecasts Potential Impact on the Insurance Industry Resulting from the Alleged Madoff Scandal, available at http://aon. mediaroom.com/index.php?s=43&itme=1445. Reports of Ponzi scheme-style financial frauds have become almost commonplace. Unfortunately these frauds were only slightly less disastrous for investors than those perpetrated by Madoff and Stanford. Minnesota businessman Tom Petters, whose company Petters Group Worldwide had acquired the Polaroid brand and Sun Country Airlines, was convicted in December 2009 in a criminal case arising out of a $3 billion Ponzi scheme involving the faked sale of electronic goods. Petters and his accomplices solicited billions of dollars in loans on the basis of fake purchase orders and invoices for electronic goods that were to be sold to big discount chains. The money from new loans was used to pay off old loans and to finance Petters’ lifestyle and business pursuits. The fallout from the scheme lead to the bankruptcy filing of Sun Country Airlines and criminal charges against an investment manager that directed funds to Petters’ operation. See, Tom Petters Found Guilty of Ponzi Scheme Fraud, available at http://www.reuters.com/article/ idUSN024978920091202. March 2011 In a scheme that ran from 2005 to 2009, a south Florida attorney sold supposedly lucrative investments in confidential legal settlements that turned out to be completely fake. See, US: Fla lawyer who ran Ponzi scheme deserves more lenient sentence because of undercover work, available at http://www.foxnews. com/us/2010/06/07/prosecution-wants-yearsprison-fla-lawyer-ran-billion-ponzi-scheme/. He managed to continue to operate the Ponzi scheme for years by initially promising and paying significant returns. As his scheme unraveled, the attorney fled in a private jet to Morocco with $500,000 in cash after wiring $16 million to an account that he controlled there. The scheme robbed thousands of investors of an estimated $1.2 billion. In Arizona, a concert promoter was accused of running a Ponzi scheme that took $25 million from approximately 140 investors between 2004 and 2007. Ponzi and financial fraud schemes have spawned a complex tangle of criminal and civil litigation. State and federal authorities are likely to bring criminal prosecutions. The Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) may bring either criminal or civil actions for violations of federal law. See, The Investor’s Advocate: How the SEC Protects Investors, Maintains Market Integrity, and Facilitates Capital Formation, available at http://www.sec.gov/about/whatwedo. shtml. Receivers and bankruptcy trustees may seek to recover assets for distribution to victims by using fraudulent transfer laws and other theories of recovery. Investors themselves may commence private party litigation in individual or class actions. In turn, the defendants will pursue any potential benefits from their insurance policies. Corporate directors and officers will turn to their directors’ and officers’ (D&O) coverages. Investment advisors, accountants and other professionals will look to their errors and omissions (E&O) policies. Coverage also may be sought under fiduciary policies, financial service institution policies, and even crime loss policies, depending on the circumstances. Some investors have gone directly to their own fiduciary, crime Financial Fraud Litigation | 43 loss, and homeowners policies for coverage. The panel will discuss these and other aspects of Ponzi schemes and related financial frauds, and the effect on professionals, directors and officers, and their insurers. THE ANATOMY OF A PONZI SCHEME • A Ponzi scheme is a fraudulent investment operation that pays investors with money received from new investors rather than from bona fide profits from the investment. See generally, Common Fraud Schemes, Federal Bureau of Investigation, available at http://www. fbi.gov/majcases/fraud/fraudschemes.htm#ponzi. A Ponzi scheme may operate for months or years if there is a sufficient income stream from new investors to pay “returns” to existing investors. To entice new investors, Ponzi scheme operators often promise unusually high or steady investment profits. A Ponzi scheme begins to collapse when the operator is unable to recruit new investments that are sufficient to pay off the growing list of existing investors. Ponzi schemes share the fatal flaw of being increasingly difficult to sustain over time. Success, i.e., the accumulation of investors expecting returns on their investment, leads to increasing demands for new investors. Eventually the operator is unable to bring in sufficient investments to satisfy the commitments to existing investors and the scheme collapses. See, Ponzi Schemes — Frequently Asked Questions, U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission, available at http://www.sec.gov/answers/ponzi.htm. Ponzi schemes take their name from the now infamous fraud orchestrated by Charles Ponzi between 1919 and 1921 in Boston, Massachusetts. Mr. Ponzi enticed investors by purporting to arbitrage international reply coupons for postage stamps. Ponzi enticed 40,000 investors to put money into his scheme by promising astronomical returns of 50 percent within 45 days and 100 percent within 90 days. Cunningham v. Brown, 265 U.S.1, 7-9 (1924) (describing Charles Ponzi’s fraud). Eventually the math caught up with Mr. Ponzi, his scheme was exposed, and he went to prison. PRIVATE PARTY CLAIMS • The nature of Ponzi schemes and related financial frauds means that investors oftentimes have very little prospect of recouping their losses from the perpetrators themselves, who have invariably either paid out the investment income to maintain the fraud, or spent the money to support an extravagant lifestyle. As result, victims of such schemes have looked to other entities — investment firms, banks, accounting firms, employee benefit plan fiduciaries, insurers, among others, in their attempts to recover their losses. Several Web sites and blogs regularly report on the progress of financial fraud and Ponzi scheme litigation affecting professionals, directors, and officers, including Kevin LaCroix’s D&O Diary (www.dandodiary. com) and the PLUS Blog (www.plusblog.org). Investors have employed a number of theories in their attempts to obtain the recovery of their lost investments. Plaintiffs often allege common law claims for breach of fiduciary duty, negligence, misrepresentation, fraud, fraudulent transfers, and aiding and abetting fraud and the breach of fiduciary duties. In addition, plaintiffs have brought claims for violations of state Blue Sky laws and violations of the fiduciary duties imposed upon employee benefit plan administrators under the Employee Retirement Income Security Act (ERISA). In MLSMK Investments Co. v. JP Morgan Chase & Co., JP Morgan was sued for negligence, commercial bad faith, aiding and abetting a breach of fiduciary duty, and racketeering by an investment company that lost money in the Madoff scheme. See, Complaint, 20009 WL 1246206 (S.D.N.Y April 23, 2009). The complaint alleges that JP Morgan Chase became aware of Madoff ’s fraud in 2008 as the result of its own investment in Madoff funds and its due diligence relating to that investment. The plaintiffs allege that despite this direct knowledge JP Morgan Chase continued to provide Ma-