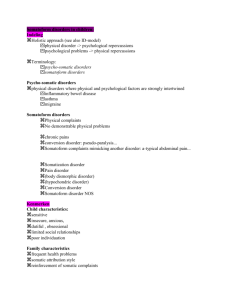

Symptom Validity Testing in Somatoform and Dissociative Disorders

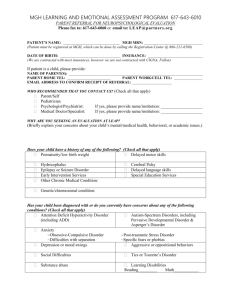

advertisement