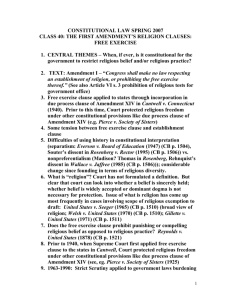

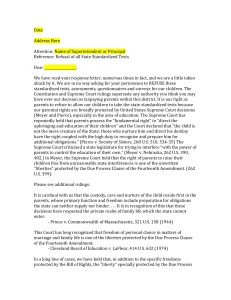

TOWARDS DUE PROCESS FOR THE FAITHFUL

advertisement