1. From 'Stone-Age' to 'Real-Time': Exploring Papuan Temporalities

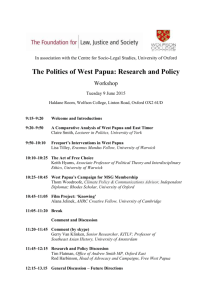

advertisement