All Faiths and None - The Church of England

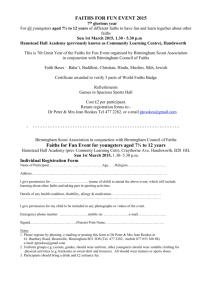

advertisement