marshall b - Center for Nonviolent Communication

advertisement

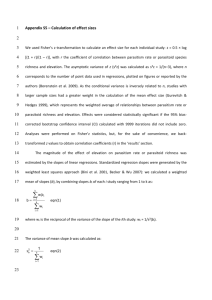

MARSHALL B. ROSENBERG, Ph.D. Interview with Terry McNally “Free Forum” KPFK, Los Angeles 90.7 FM Aired on October 18, 2001 (Pre-Recorded on October 7th, 2001) Hello. I’m Terry McNally, and welcome to “Free Forum” and thank you for joining us. Because my guest has such a busy travel and training schedule, we had to pre-record this interview; and it happens that the time we found to do so is the evening of October 7th – the day the United States and Great Britain have initiated a military response to the terrorist attack of September 11th. Following that attack, in the few days afterwards, tonight’s guest, Marshall Rosenberg – who has worked for thirty years to spread the practice of what he calls “Nonviolent Communication”, wrote these words: “If the goal becomes retaliation and punishment each action will be determined by the answer to this question: ‘Will this action take us closer to punishing those responsible for the pain we have suffered?’ On the other hand, if the goal is peace and safety for the world each action will be determined by answering a very different question: ‘Will this action bring us closer to lasting peace and safety for the world’.” Months ago, when I began pursuing an interview with Marshall, I assumed it would be primarily about language and communication and focus at least a bit more on personal relationships than international crises. Once scheduled for this evening, I knew we would deal with possible responses to September’s attack; but, as you can see, events have consistently conspired to change and heighten the context of our conversation and make it, I think, more and more relevant. Here on “Free Forum” we explore the lives, the work, and the ideas of individuals that I suspect hold pieces of the puzzle of a world that just might work. We look at new and innovative and provocative models in business, environment, health, science, politics and media – all based on the fact that I believe we can do better, and I want to help you and myself find out how; and that’s as true tonight as it ever is. Marshall Rosenberg is the founder and director of educational services for the Center for Nonviolent Communication®, an international non-profit organization. In 1961 Dr. Rosenberg received his Ph.D. in Clinical Psychology from the University of Wisconsin. Nonviolent Communication training evolved from his quest to find a way of rapidly disseminating much needed peace-making skills during the civil rights struggles of the early 1960’s. Dr. Rosenberg provides Nonviolent Communication training in Sweden, Switzerland, Italy, Germany, Denmark, Belgium, Austria, Malaysia, India, the United Kingdom, Netherlands, France, Canada, as well as the United States. He and the Center are also active in war-torn areas and economically disadvantaged countries, offering Nonviolent Communication training to promote reconciliation and peaceful resolution of differences. McNally: Welcome Marshall Rosenberg to KPFK and “Free Forum.” Rosenberg: Thank you Terry, I’m glad to be here. McNally: Although we will certainly deal with today’s events my first question, as it always is on “Free Forum”, Marshall is about your personal path to the work that you do today, and I invite you to go back as far as you want. Take as long as you wish-childhood dreams, mentors, models, turning points. We want listeners to get to know the person behind the ideas and the work that you’re doing. Rosenberg: Terry, I trace the work I do back to 1943. McNally: Wow. Rosenberg: I was living in Detroit at the time. My family had just moved there – just in time for the race riots of 1943, and we were locked in the house for four days while the riots went on, and there were about 32 people killed in our neighborhood, and that was a very powerful learning experience for me as a young boy. It taught me that this is a world where things like your skin color or your name could be a stimulus for violence. And that put in my head a question that’s been there ever since; which is: What happens to people that they enjoy other people’s suffering? That they want to hurt people? Now the theory that’s been around for many centuries is that that happens because people are innately evil, or selfish, or violent. But I saw that there were people that weren’t like that. I saw that there were many people that enjoyed contributing to one another’s well-being. So then I wondered how come some people do seem to enjoy other people’s suffering while other people are just the opposite? They enjoy contributing to people’s well-being. And it was those questions that led me to the kind of work that I’m doing now. When it came time to go to the University, I picked clinical psychology hoping I could find some information relevant to those questions of what leads some people to enjoy others’ pain and others to want to contribute to their well-being. And in clinical psychology, I was exposed to the belief that people get mentally ill, and that’s the cause of it. But, in the course of my studies I came to see that that was an overly-simplistic view of things – that it wasn’t that simple – that all there was was an illness that we could somehow cure. I began to see that it had much more to do with the way people are educated and that some people are educated in a way that makes violence enjoyable. Then what scared me, I started to see that this was the systematic way that most people were being educated, and so I’ve made it my work ever since to show people what I believe are the ways that we are educating ourselves that is contributing to the violence, and showing ways that we can educate ourselves that 2 will make people much more interested in contributing to one another’s well-being than to their pain. McNally: Um, so you’re saying that you found it to be an education problem and so your approach has been an education solution. Rosenberg: That’s right. I see it as an educational problem, but that educational problem is part of a broader problem. Then we have to ask “why did we get educated in this way that creates the violence?” And my exploration into that question leads me to believe that we educate people this way to fit the kind of social structures that we have been creating for several centuries – what Walter Wink, the theologian, calls “domination structures” in which a few people dominate many. And when you have structures like that, it’s necessary to educate people in a certain way to fit those structures; and a by-product of that is to make violence enjoyable. McNally: Let me ask you, when you’re using the word “education”, you’re meaning that very broadly, I would assume – you don’t mean just that that’s what people get in school? Rosenberg: No, because as I’m using “education”, it’s been going on for centuries before we had public education. McNally: So, where does that education come from? Rosenberg: It comes from what you might call the story that every culture has – a kind of way that people are just taught by their parents, by the church, by the community; about what the good life is; about what is the heroic image. Every culture has this kind of story that they teach people. But we have been teaching a story that leads to rather violent consequences for many hundreds of years. McNally: Tell you what; let’s circle around, Marshall, and return to the story and the meaning of what you’ve seen as possible solutions to that story and its effects; but let me tell people first, you’re listening to “Free Forum” on KPFK Los Angeles, 90.7 FM. I’m your host, Terry McNally, and we’re speaking with Marshall Rosenberg, founder of the Center for Nonviolent Communication®, and author of Nonviolent Communication: A Language of Compassion, and you can learn more about that at www.cnvc.org, and on that website you can also find, occasionally there are free workshops; free trainings in Santa Barbara, and I believe there’s one coming up fairly soon, so check the website for those. They come up intermittently. Um, what I was going to say is let’s go back to the unfolding theory and so on, but let me also first get a little more of your personal story; so, you were struck as a child? You were kind of focused on that question. You went to school, and then what? Rosenberg: I went to the University, and got a doctor’s degree in psychology, but in the course of getting that degree, I saw that the study of clinical psychology – I didn’t think that it really answered the question in the depth that I wanted – which is 3 how come people act in this violent way? Clinical psychology took the approach that this was, as I say, some kind of mental abnormality and that we could cure it with some kind of psychological therapy, and I saw that that kind of view did not take into consideration the kind of social structures that we’re living in and how they educate people, and by making such a narrow focus, as though there’s some kind of illness that accounts for this violence – that it was actually getting in the way of our learning more how to cope with this violence. McNally: Sure, if the violence is actually more a norm than an aberration. Rosenberg: Exactly. McNally: And that those who choose not to be violent in obvious active ways may still be being violent in more subtle ways. . . would be my guess. Rosenberg: Yes. McNally: And I referred in the introduction to your work in civil rights. Could you tell us a little bit about – as I say, weave that story a little bit about where you began to practice – take your interest in this question into the real world? Rosenberg: Well, before we get to that, then, I need to put another part in there. . . McNally: Go right ahead. Rosenberg: . . .which is where I got dissatisfied with clinical psychology for answering these questions that were on my mind. I was dissatisfied with the approach that clinical psychology took which is to look at what is pathological and try to fix it rather than starting with another question which I thought would be more helpful, which is: “How are we meant to be? What is our nature? What is the person who’s functioning as human beings were meant to function? What do such people function like? So I then started to do a quick study of comparative religions to see what all of the religions defined as the answer to this question: “How were we meant to live?” And I began studying people who I really valued and I started to see that there were many people who didn’t get caught up in all the violence; that they had a different way of looking at the world and so it was by studying such people and trying to extract from studies of comparative religion that I came to the answer to the question of “How were we meant to live?” and that answer came out that we were meant to contribute to one another’s well-being; that that’s really what human beings like to do more than anything else. But the reason that we’ve turned out so violent is not in our nature but, as I have said, our education. So in putting together how I thought we were meant to connect with each other, I pulled together a process of communication whose purpose is to help us to connect in a way that enables us to do what I think is really our nature which is to contribute to one another’s well-being. And I was then in private practice 4 and offering what I was pulling together, this process of communication, to families that were having trouble communicating with each other; to people who were having trouble with the people that they were working with. And this process that I pulled together was providing a great support for such people. And then some people who were working in race relations heard of my work and invited me to begin working on getting black and white groups working cooperatively together, and this subsequently led me for about thirteen years to do a lot of work on civil rights around the United States. McNally: Uh huh. And those years would be? Rosenberg: That would have been from about 19. . . oh, let’s say 67 or so to about 1980. McNally: Mmm hmmm. Long time. And my guess is that once that became your focus, that it’s unlikely you returned back to private practice dealing with individuals and families; am I correct? Rosenberg: Yes. Once I started on that route, and I saw how valuable the process I was teaching was, then I wanted to see if I could teach other people how to teach it; to start to set up communities of people in different parts of the United States that themselves could provide the training where it would be most useful. And so then that was the end of my private practice. From that point on, I’ve been traveling. McNally: And that traveling is to train as well as to utilize Nonviolent Communication in difficult situations? Rosenberg: Yes. And so, after the race relations work, some people in Europe began to hear of my training and invited me to come to countries in Europe, and offer the training to people in various conflict situations; and then in recent years, we have been going into war-torn countries like Rwanda, Israel, Palestine, Serbia, Croatia, Ireland – and identifying people in those countries who find our training valuable, and with them, creating teams that make the training available where it can be doing the most good for the peace efforts. McNally: Okay. Let me tell people – you’re listening to “Free Forum” on KPFK Los Angeles, 90.7 FM. I’m Terry McNally, and we’re speaking this evening with Marshall Rosenberg, founder of the Center for Nonviolent Communication® and author of Nonviolent Communication – A Language of Compassion, and you can learn more about the book the trainings, the concepts and when trainings are available in the area at www.cnvc.org. Okay, um, let’s talk now about when you ask the question “Why people want to be violent” – you then saw a better question: “What’s the state that people really want to be – what’s the ideal state of human relations?” You then found what you call “Nonviolent Communication” as a method to help human beings approach that intended state. What is Nonviolent Communication? How does it work? 5 Rosenberg: It basically focuses on two questions: “What’s alive in us”, and “what would make life more wonderful”. And so Nonviolent Communication shows us a way of expressing nakedly what’s alive in us – how we are, in other words – without any criticism, without any analysis of others that implies wrongness. The training is based on the assumption that anything that people hear coming from us that sounds like a criticism, or sounds like an analysis of wrongness on their part gets in the way of our connecting in a way that everyone can end contributing to one another’s well-being. Part of it is to say clearly what’s alive in us without criticism. Another part is to say clearly what we would like to make life more wonderful, and to present this to others as a request and not as a demand. So the training shows how to communicate from ourselves to others this way and it shows us how to hear this same communication in the messages of others, regardless of how they speak. This is one of the things that people like most about the training. The other person doesn’t have to have been trained in it for us to connect with them in a way in which we can end up contributing to one another’s well-being. McNally: So it’s not only in how you speak, it’s in how you listen. Rosenberg: Exactly. Our expressions from ourselves to the others, and how we receive others’ messages to us. McNally: Okay. Let’s get more specific. Um, in asking “what’s alive in us”, what does that end up meaning? In a. . . you can choose a specific example. Rosenberg: Well, let’s say that, as I said, I give an example in my book of one time when I was in a refugee camp in a country not very friendly with the United States, when a gentleman heard from my translator who was introducing me that I was from the United States, he immediately screamed, jumped up and screamed at me ,“Murderer!” Now our training suggests that any criticism, any analysis that implies wrongness, any insult is basically an expression of what that person’s needs are that are not getting met. So, in that situation, what’s alive in that person, as we look at it, is “what need of this person is not getting met that would lead him to communicate that way?” What’s the need behind him calling me a murderer? And we also try to find the feeling that goes with that. What kind of pain is resulting in that person – as a result of that need not getting met? So, our training teaches us how to try to connect with that. Now, this involves some inference. We need to kind of infer “what could this person’s needs be when he hears that I’m an American and he calls me a murderer? Here’s what I said back to him – I had to guess; I didn’t know for sure. I said “Are you feeling annoyed because your need for support is not getting met by my country in a way that you’d like?” I had some clues to go on at that particular time, but even if I’m wrong in guessing that, notice what it tells the other person. It tells the other person that no matter how you communicate, I’m interested in what’s alive in you. 6 McNally: So what you’re saying with that one, Marshall, is that you don’t have to be right; you don’t have to guess correctly; but you’ve shifted something as soon as you express an interest. Rosenberg: If it’s sincere, sincerely trying to connect with what is alive in this human being. And in this case, I happened to guess right. He said, “Yes, you’re darned right, we don’t need your weapons being sent over here. We don’t have housing. We don’t have sewage.” So I stayed with what was alive in him. I said, “So you’re saying sir, if I’m understanding you correctly, that when you don’t have such basics as housing and sewage, it’s very painful to have weapons sent over.” And he again said, “Yes.” And then he said, “Do you know what it’s like to live under these conditions for twenty-eight years?” And again, I kept my attention on what he was feeling and what he was needing. In other words: what’s alive in him. An hour later this gentleman invited me to a Ramadan dinner at his house. We now have one of our schools in that refugee camp. Schools where all of the students, teachers and parents are trained in Nonviolent Communication. McNally: Okay. Now, could you shift it just to a much more local interpersonal kind of an experience just to demonstrate the same thing, because one thing that I can tell from this, and from reading the book and having taken one of the one-day workshops is that it’s clear – it’s very clear. It’s elegant almost. But our habits and our learning of other ways is so strong that to make a listener really get it clearly, let’s go – could you do another example – but one that’s, you know, just a couple of folks together – a relationship; a husband and wife – that sort of thing. Rosenberg: Well, let’s take one that happened right there in Santa Barbara one time. The woman came to one of the trainings and she said “Marshall, how do I get my son to pick up the clothes in his room?” And I said “Is that your objective?” And she said “Yes.” And I said “Then he’ll probably resist.” And she said “what do you mean?” I said, “If you have single-mindedness of purpose where all you are interested in is getting what you want and the other person senses that, even if they want to cooperate, there’s a part of them that wants to resist anyone who has set out to change them.” So she said, “So in other words, I have to just do all the picking up in the house myself?” I said, “No, let me show you another option besides just giving up your need or setting your objective of trying to get him to do what you want. The goal of Nonviolent Communication is to create a certain connection; so start by telling your son what is your need in this situation.” She said “I want him to pick up the clothes in his room.” I pointed out to her that that’s not how we define a need. A need is not any reference to a specific person taking a specific action. It’s the internal need that would be satisfied by the action that I told her would be helpful to start with. “What is your need?” And it took her awhile because the people that come to our trainings are not trained in 7 needs; they’re not trained to be conscious of them or to express them. McNally: No one is. Rosenberg: And that again goes back to these historical reasons that I mentioned earlier, that if you’re training people to be nice dead people in domination structures, the last thing you want to teach them is what they’re needing because people do not make good slaves when they are conscious of their needs. McNally: Right. Rosenberg: So, I helped her with this and finally she saw that her need was for order, first of all, and for some support in maintaining that order; and we worked with her on how she could make that need clear to her son and then after making that need clear, then make the request “Would he be willing to pick up the clothes.” And then she said “But what if he says ‘no’?” Then we showed her how no matter what he says, even if it’s “no”, how to hear what needs of his keep him from cooperating. So we showed her how to express her needs and requests to begin with, how to hear what his needs would be regardless of how he answers, and once there is that connection where both parties understand each other’s needs, then we show how to go to requests, strategies; how to look for ways of getting everybody’s needs met. But it’s that connection that’s important. When the person feels that the person is 5 or 55, they feel that their needs are equally as important to us as our own. But if people sense that we are only out to change them, it stimulates more resistance than cooperation. McNally: Okay, so the first two steps – oh, you’re listening to “Free Forum”, KPFK Los Angeles, 90.7 FM. I’m Terry McNally and I’m speaking with Marshall Rosenberg who is the founder of the Center for Nonviolent Communication® and the author of Nonviolent Communication – A Language of Compassion, and information about both are available at www.cnvc.org. So I see the first step is observing; and it’s observing the other person, or yourself, or both? Rosenberg: Well the observation in the case of the mother, for example, would be that she has observed that he hasn’t picked up the clothes in his room. Now we show people how to make clear observations – how to say exactly what you have observed without bringing in any kind of evaluation. So you say “I see you didn’t pick up the clothes in your room.” Not “Your room is a mess”, or not “You’re being lazy.” Just the facts to start with. And then we go to the part where we say what’s alive in us. What’s alive without making any criticism. McNally: And that’s our own, so it’s “I see this and I feel this.” Rosenberg: “I feel this” and then my feelings are connected to my needs. I feel this way because I’m needing – and then you bring in your need, and then you end on a clear request – what you would like the other person to do. 8 McNally: Observe, feel, need, request; and they’re all hooked. Now where in that would you. . . would you do that all focused on yourself first? In other words, or when. . . or when. . . or. . . yes, do you do all of that and then make your request and then when they respond, then begin to say – begin to inquire about what their need is? Rosenberg: Exactly. For example, if the other person says, “I don’t want to”, our training shows how to try to hear the need behind the “no”. If the person judges us and says, “you’re always pickin’ on me”, “you’re too demanding”, we hear the need behind the criticism. So no matter how the other person responds to us, the training shows us how to connect with what that person is feeling; what they’re needing. McNally: So, it sounds like a real crucial thing in this is that it’s not as much about what people do as about what people need; and if you can relate to each other by caring about what each other needs, and trying to help get needs met, you’ve changed the whole – the whole what – the whole dynamic for sure, but you’ve changed any feeling of being a target for instance… is that what’s up? Rosenberg: I think that’s pretty close. When the other person trusts that we are not judging them moralistically “wrong”, “bad”, “evil”, “selfish”, we are just expressing ourselves. When they trust that; that we are not judging them, that we are being honest with them without judging; when we are making requests without demanding, and when they trust that we are equally as interested in their needs getting met as our own, then what I’m saying, Terry, is I get into a lot of conflict situations in my work, and it’s rather miraculous that when both parties are at that point, they see each other’s needs; they trust that the other person values their needs equal to their own. It is amazing, then, how conflicts that would seem to be totally unsolvable almost seem to solve themselves. McNally: Uh huh. And, I just want to quote a couple of things that I’ve heard you say about both of these because I thought they were just wonderfully put. One was “These techniques allow you to make conscious choices about how you will respond whether you get what you want or not.” And you’ve talked about that – that the person doesn’t actually have to do or change, but you can still respond – you can be just more conscious and responsible about how you respond when that happens. Rosenberg: But it’s not just that we end on this kind of understanding and tolerance; we do get to action – we do want to end on actions being taken so that everyone’s needs get met. So that the connection – what we call an empathic connection that takes place between the two parties. But we don’t stop there. Then after the empathic connection we do need to look for concrete ways of getting everybody’s needs met. McNally: Uh huh. So at that point – how you respond whether you get what you want or not, is not the end; it’s not a resignation nor 9 some sort of a renunciation of your need in some sort of spiritual way. At that point you continue on, but in a different transaction – a transaction that’s about getting each other’s needs met. Rosenberg: Exactly. You see, when we say “get what you want” – that’s a strategy, that’s what we call a request. You may not get what you are requesting, but if you’re conscious of what your needs are, we’re confident that you can end up getting your needs met. McNally: Uh huh. And so what you learn is to make the distinction yourself between your action requests and your underlying feelings and needs. Rosenberg: Very different, and very important to see that difference. McNally: Yeah. We’re at the half-way point. You’re listening to “Free Forum” on KPFK Los Angeles 90.7 FM. I’m Terry McNally and we’re speaking with Marshall Rosenberg. Marshall is the founder of the Center for Nonviolent Communication® and author of “Nonviolent Communication – A Language of Compassion”. And the website to learn more is www.cnvc.org. Okay, one other thing you said which I want to quote and then you can expand on that; as you’ve said a couple of times already this evening – this approach to communication emphasizes compassion as the motivation for action rather than fear, guilt, shame, blame, coercion, threat, justification for punishment – any of that. And then you say, in other words, it is about getting what you want for reasons that you will not regret later. Expand on that. Rosenberg: Well. . . McNally: . . . and if you want to refer to perhaps the current situation we’re facing internationally – that statement did strike home to me. It’s about getting what you want for reasons you will not regret later. Rosenberg: You see, if you start with the assumption that people are basically evil or selfish, then the correctional process if they are behaving in a way you don’t like is to make them hate themselves for what they have done. If a parent, for example, doesn’t like what the child is doing, the parent says something like “Say you’re sorry!!” The child says, “I’m sorry.” The parent says “No! You’re not really sorry!” Then the child starts to cry “I’m sorry. . .” The parent: “Okay, I forgive you.” You see, that approach is at the basis of our conflicts with children, with criminals; we’ve been educated to believe that you have to make a person suffer for what they’ve done – to hate themselves – to be penitent – we call our prisons penitentiaries. McNally: And the logic there is if you can make them hate themselves enough, they’ll change. 10 Rosenberg: Yeah, they’ll hate themselves enough to change. Now that’s the theory; it doesn’t work too well. I think it works just the opposite, that the more you get a person to hate themselves, the more they behave in the ways that we don’t like. Our prisons don’t work. We see from our prisons from the very beginning our statistics show that if two people – same act – one goes to our prison and one doesn’t, the one that gets put in the prison is far more likely to behave in a violent way when they get out than the person who doesn’t go in. So this system doesn’t work. It doesn’t work whether we’re dealing with children in our families, with criminals or with other countries who behave in ways we don’t like. Punishment is a losing game and we’ll see it if we ask ourselves two questions. Question Number One: What do you want the other person to do differently? If you ask only that question, you can make a case for punishment; you can probably think of a time when punishment has influenced somebody to behave as we would like. But if we ask the second question, I’m confident that we will see that punishment never works. And the second question is this: What do we want the other person’s reasons to be for behaving as we would like them to behave? I would maintain that if we stop and really get conscious of that we obviously want people to act because they see how it will serve life, and to enjoy doing it for that reason. It’s natural to enjoy things when we do it to enrich life. But punishment gets in the way of that. McNally: Uh huh. And punishment also, I mean, yeah, punishment has to do with domination and people who feel dominated may change behavior, but like self-hatred, a feeling of being dominated is not the kind of thing that creates a society of healthy vital people. Rosenberg: Yes. When we use punishment it justifies violence; it implies that you have judged that you are right and the other person is behaving in a way that you defined as bad. They deserve to suffer for what they’ve done. This is the essential training and thinking we’ve had over much of the planet. McNally: Before we speak specifically about the confrontation right now between terrorism and its victims, can you talk a little bit – or give me an example or two of how some of this Nonviolent Communication has worked in practice in places – in some of those conflict places that you have tried it; in addition, you know, you gave the one about a specific individual who started out with a certain attitude and you ended up, you know, now there’s a school there and they train and so on, but have there been some other examples you can give us that can sort of demonstrate that the fruitful use of this in tough international situations? Rosenberg: Well, I was invited to do a mediation between two tribes that were at war in northern Nigeria. One tribe was a Christian tribe and the other was a Muslim tribe. In one year’s time there was one quarter of the population in this village killed in this 11 struggle. My colleague did the real hard work here; he worked with both sides to get them in the room together. This is, in mediation, often one of the hardest things to do--just to get the people to get into the room together. So he used our training to go to both sides individually and then when each side said basically the same thing: “You can’t talk with these people; the only language they know is violence.” We used our training to empathically connect with their fear of negotiation, their rage, their desire to protect themselves, and only seeing punishment and violence as a way of getting there. So he heard this on their part and then he came from his heart, explaining how he was convinced that other ways existed for resolving this to everyone’s satisfaction. And after six months of his hard work, they finally agreed to meet with me. Now of course in that six months, 65 people were killed by the time we could get them all into a room together. Okay, so now I’m in a room with about twelve chiefs from both tribes on either side of the table, and I start with a question, which is central to what’s alive in us. I ask both tribes, “What needs of yours are not getting met in this situation?” And immediately, instead of answering my question, members of both tribes start to make judgments of the other side. One of the chiefs screams across the table, “You people are murderers!” and what comes back from the other side is, “You people have been trying to dominate us for 80 years! We’re not going to put up with it anymore,” and they’re screaming at each other. My question was “what needs of yours are not getting met?” So, what I do in a situation like that is to translate their criticisms of the other into what needs are being expressed behind them. So I said to the Chief who said “You are murderers”, I said, “Chief, when you say that, are you trying to communicate your need for safety and how you want any conflict, no matter what, to be resolved in some way other than violence?” He had to stop and think for a moment because notice I’m focusing his attention on what’s alive in him rather than on his judgments of the other side. But after a second or two he said, “That’s exactly what I’m trying to say.” Okay, so I’d helped him, then to get clear what his needs are, and now I say to the chiefs on the other side of the table, “Would somebody on the other side please tell me back what you heard the chief say?” It’s not enough that we get them to express their needs. We have to be sure that the other side hears their need, because when that connection is there, they see the other person’s need, they see a human being – not the enemy image they had. McNally: And there’s the empathy, right? Rosenberg: Well we wouldn’t want to call this pure empathy. At this point, I’m just wanting. . . McNally: . . .but, but I mean there’s the potential; there’s the foundation – it could happen. . . Rosenberg: . . .I’d say it’s a rudiment of empathy. It’s a start toward empathy. 12 McNally: Right. Rosenberg: Just to hear the needs without getting the enemy image all mixed in. So I did this for both sides. Whenever they were screaming their insults, I would translate it into a need. I would get the other side to hear it. After about an hour and a half of this one of the chiefs jumped to his feet and said something to me very intensely and I had to wait for my translator to translate it since they were all speaking a language I don’t speak, and I liked very much what the message was that this Chief said to me after his watching this for just about an hour and a half. He said to me, “If we communicate this way, we don’t have to kill each other.” And it didn’t take much longer for us to resolve the conflict to everybody’s satisfaction – once everybody’s needs were on the table. Once they were seeing each other’s needs rather than the enemy image. McNally: Okay. You’re listening to “Free Forum” on KPFK Los Angeles 90.7 FM. I’m Terry McNally and we’re speaking with Marshall Rosenberg, founder of the Center for Nonviolent Communication® and author of: Nonviolent Communication – A Language of Compassion. The website to learn more is www.cnvc.org. Okay, let’s move to the events we’re facing today and in this time. This interview is being recorded the evening of October 7th. This morning, in our time, this morning the U.S. and Great Britain launched a military response to terrorist attacks of September 11th. Let me repeat the distinction that I quoted you making before in the interim between September 11th and today. “If the goal becomes retaliation and punishment, each action will be determined by the answer to this question: ‘Will this action take us closer to punishing those responsible?’ If the goal is peace and safety for the world, each action will be determined by answering a very different question: ‘will this action bring us closer to lasting peace and safety?’” Now what I’d like to do also, Marshall, if you’ll bear with me for a second, is read a couple of quotes from President Bush and from Osama Bin Laden. There was a tape released today – I don’t know how long ago he recorded it, but it was released today. And I’m going to quote a little bit from both of them, and then I want you to talk about your reactions to what’s going on right now. President Bush says, “More than two weeks ago I gave Taliban leaders a series of clear and specific demands to close terrorist training camps, hand over leaders of the Alcaida and return all foreign nationals. None of these demands was met and now the Taliban will pay a price. We are supported by the collective will of the world. Our military action is designed to clear the way for sustained comprehensive and relentless operations to drive them out and bring them to justice. As we strike military targets, we will also drop food, medicine and supplies to the starving and suffering men, women and children of Afghanistan. The United States of America is a friend to the Afghan people. Today we focus on Afghanistan, but the battle 13 is broader – every nation has a choice to make. In this conflict there is no neutral ground. If any government sponsors the outlaws and killers of innocents, they have become outlaws and murderers themselves and they will take that lonely path at their own peril.” That’s President Bush. Osama Bin Laden in his tape said: “These events have split the world into two camps: belief and disbelief. America will never dream or know or taste security or safety unless we know safety and security in our land and in Palestine. God has sent one of the attacks and has attacked one of its best buildings.” I mention that because that was his explanation of whether, of who was responsible for those attacks. Okay, having set up the language they’re both using, what’s your response to what’s happening? Rosenberg: My response is that both sides have the same needs. You see, all human beings have the same needs. Notice neither one of those comments that either of them made was expressing what their human needs were. It was rhetoric, political rhetoric. They were talking about their analyses, their beliefs. They weren’t expressing their feelings, their needs or their requests. When we get lost in that dangerous rhetoric is when many people are going to get hurt. So if I were with both of them, let’s say we had them in a room screaming what they just said across the table at each other, I would translate those messages into their needs. What I would say to Mr. Bush would be something like, “President Bush, I’m hearing you say that you’re aghast at what has happened and you have a need to protect the American people. Is this what you’re saying?” I would turn to Bin Laden and say, “I’m hearing that you are in enormous pain because some of your primary needs have not been met by actions taken by the American government in the past. Let’s get these needs out on the table and look for a way to get everyone’s needs met. Let’s get away from the rhetoric implying wrong evil people. Let’s talk the language of human needs – we can get everybody’s needs met if we keep the focus at that level.” McNally: Marshall, you told a story about the tribes. Rosenberg: Yes. McNally: Do you really believe. . . well, also, you did preface it by saying that your partner had done the hard work of getting the two people in the room. [laughter] Rosenberg: The two groups – the two tribes. McNally: Yeah, I mean, I’m saying I -- you know, the idea of getting these two groups in a room is. . is. . I can’t even imagine happening. But, Um, do you really think that what you’ve said – I mean, in what realm of possibility do you think that exists? Rosenberg: The possibility of getting them in the room? Or the possibility of once you get them in the room finding a way to get everyone’s needs met without violence? 14 McNally: Why not both? Let’s take on both. Because obviously if we’re going to solve these problems differently it’s going to take both. Rosenberg: I would say that both are possible; the first is the hard one for me. It’s been very hard for me to try to get access to Mr. Bush myself. I’ve tried. So the getting the access would be difficult, but not impossible. Once you got them into the room, then I’m very optimistic. And now, let’s not mix up what I’m talking about with the kind of talks that usually go on between these political groups. Like we see how the Israelis and the Palestinians have had talk after talk for years. I’m not talking about that kind of talk. I’m talking about where you get both sides connected at the need level. You don’t let them get lost in political rhetoric. You get both sides seeing the humanness of each other, and looking for a way to get everyone’s needs met. I’m very optimistic of what could happen. Now, there are a lot of people who have judged me as pretty naïve when I say that. They have images that some people are just basically evil. My experience has been that that concept of things just makes matters worse. It leads to self-fulfilling prophecies. If we believe that people are evil, then therefore they have to be punished or killed. You provoke in other people the very behavior that convinces you that your stereotype of them is true. McNally: Now, okay, let me ask first a quick question, which is: have you been in a situation that is at all similar to this where this hasn’t worked? Rosenberg: Yes. I was in a situation. . . well, not at that level. For example, down in San Diego I was once working with two street gangs and they had had a lot of violence between the two and the social worker who had access to both groups got them into a room with me; she got them to agree to be in this room – they would only agree to this for two hours. And they spoke Spanish, I didn’t speak – I had to have a translator. In those two hours we didn’t get there. I’m confident if we had two days we would have. But at that point, we could only get them in there for two hours. McNally: Okay. So it hasn’t been universally successful, but your feeling is that – okay, I appreciate that. Now, when someone says that God had sent one of the attacks and has attacked one of its best buildings, that statement sounds to me like this man is outside of consensus reality. I’m reminded of Adolph Hitler, Edi Amin, Charles Manson. Now, how do you communicate with evil, or how do you communicate with psychosis? Rosenberg: First of all, when you’re labeling that way, I think you’re part of the problem. When we label the person as psychotic or evil, we are engaged in a process of thinking that I think is, itself, part of what leads to the violence. So what do I say if I’m in the room with Mr. Bin Laden and he says that. . . McNally: . . . and, and remember, this is someone who says that and, and let’s just assume, because we don’t know, and I will. . . let 15 me say this – that I don’t think – as far as I know, we don’t have proof – but let’s leave that aside ‘cause we’re having. . . you know. . . and let’s say that the man was instrumental in the takeover of those airplanes and the mass-murders, and destruction that took place and then says that God did it. So two things: One capable of deliberate – in cold blooded longterm deliberation – strategic deliberation of that kind of act and then attributing it to God. Rosenberg: I would do what our training teaches people to do: Don’t hear what the person thinks; hear what’s alive in the person that is at the root of what they’re saying. So when he says this about God I would say something to him like, “Mr. Bin Laden, are you expressing that you’re in a lot of pain because basic needs of yours have not been met by the American Government?” I don’t get wrapped up in this rhetoric of God did it or that. . . we focus on what’s alive in the person; what they’re feeling; what their needs are. McNally: So what you’re saying is that, while to me that sounds like someone has. . . has constructed . . . remember we started very early saying that it had to do with stories – the story, right? Rosenberg: Yes. McNally: Now it looks to me like we have a confrontation here between needs, but also between stories. And I don’t fully, you know, in other words, let me say one other thing – that I absolutely agree with what you said about the question of what question the United States would ask to arrive at its action. You know? In other words, I think if you ask what will bring safety to the world, you might act differently than what will punish those responsible. I agree with that. But having said that, you know, this person, it seems, I mean, what I’m saying is that I don’t absolutely agree with George Bush’s story, but I certainly think that Osama Bin Laden and those men who were willing to flight train, live in neighborhoods, take a long time to live with the idea that at a certain day they were probably going to commit suicide and murder – that they’ve got a very different story; and I’m not sure -- I’m asking you… yes, they have needs, but can that ever overpower that story? Rosenberg: I think that they have the same needs that we do. We have the same needs that these people that we call terrorists have. Our difference is in strategies for meeting our needs, and what kind of intellectual justification we have for using our strategies. So, they have this belief that the Americans are evil and deserving of being punished, and Mr. Bin Laden expresses that in this abstract way that it’s God that did it. But he’s basically saying he judged that the Americans are evil in the way they are doing certain things and need to be punished. McNally: . . . and deserving of punishment, yes. And one thing I did notice, by the way, Marshall, was both of them said “the world is divided into two sides”. They both did. 16 Rosenberg: I would stay away from that rhetoric because both sides have the same needs. I would help both sides see that they have the same needs, and that there are ways of getting everybody’s needs met. But I doubt the violence is going to get there. Now, let me say one thing we haven’t said so far. . . McNally: . . .the idea of protective force? Rosenberg: Yes. McNally: Okay. Rosenberg: I am not saying that force at times is not necessary, but if somebody is about to do something that is threatening to our needs, we use whatever force can protect ourselves. The use of such force is not to punish people. It’s not based on an idea that they’re evil and need to suffer. It’s based on simply protecting our needs. So if we want to have force for that purpose, that’s not in conflict with what I’m saying. McNally: So in asking the question, “What can make the world safe?” protective force is maybe a piece of what arrives as an answer to that question. Rosenberg: Yes. It may be necessary to get to the place where we can get both sides together, and force to protect against the violence continuing may have to be used in order to get to this place where both sides could get together in the way that I’m talking about. McNally: Okay, Marshall, we have two minutes left. What might you suggest people/listeners might take from this, given the situation we’re in? Rosenberg: I would hope that they would put their energy into getting both sides into the kind of negotiations I’m talking about. Not the usual rhetoric of back and forth against each other, but getting representatives of both sides together hearing each other’s needs. I am confident that everyone’s needs can get met if we communicate at that level and not at this level of who is the most violent and deserving of punishment. McNally: And a final question. This is framed in terms of language and framed in terms of communication. It’s really about something bigger and deeper than that, isn’t it? Rosenberg: It is based on a spiritual belief that I have that human beings like nothing more than contributing to one another’s well-being. It’s our education that leads to the violence – not our nature. So if we can have a communication that focuses our attention where we can do what comes naturally, which is contribute to one another’s well-being, we’ll be amazed at how conflicts which seemed impossible to resolve when there is this connection at the human level – people see someone with the same needs and we see no enemy images – then I’m convinced that everybody’s needs can get met without violence. 17 McNally: Yeah. I have to say I don’t share your confidence in all cases, but I share a great deal; and what I heard in the last thing you said, actually – and I’m taking it a little bit away from the international situation we have right now – but in our own lives, that it works both ways: If you can change the education and change the story, you will probably change the communication. But if you have people that begin to pay attention to their needs and the needs of others that will begin to change the story. Is that true? Rosenberg: If I understand you, the two can interact. McNally: Yeah. In other words, we can operate – we can either change the story of western – of modern civilization – we can work at that; but if we start individual by individual – having people change this orientation and begin to listen to each other’s needs, that will, people who behave that way will eventually change the story. Rosenberg: Exactly. McNally: Okay. You’ve been listening to “Free Forum” on KPFK Los Angeles, 90.7 FM. I want to thank you again Marshall Rosenberg, author of Nonviolent Communication – A Language of Compassion, founder of the Center for Nonviolent Communication® on the web at www.cnvc.org. My thanks also to Ian Johnston, my engineer, and to you, my listeners. If you have questions, comments, guests or issues you’d like to hear about on the show, e-mail me at temcnally@att.net. These are very, very trying times for all of us and I wish you all the best. I look forward to being with you again in two weeks. 18