:(1)different types of seating arrangement (2)the effects of seating

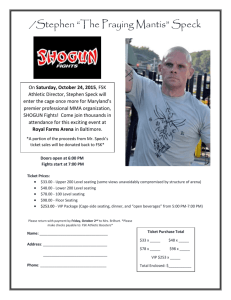

advertisement

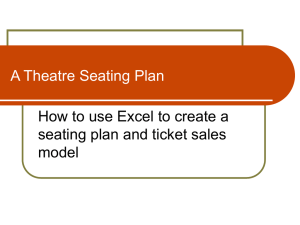

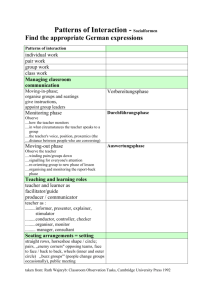

Seating Arrangement Content: Introduction 1 Part One: The impact of seating arrangement on students 3-7 Part Two: Different types of seating arrangement in the classroom 8 – 13 Traditional Lecture Theatre style Circle, Square and Rectangle – Open Circle, Square and Rectangle – Closed Partial with Open Area (U-shape seating) Group Work Semi-circle arrangement Table rows others Part Three: The consideration of seating arrangement 14 - 20 Conclusion 21 Reference 22 - 23 1 Seating Arrangement Classroom Seating Arrangement Introduction: On the surface, seating arrangement to some teachers is less important to the learning outcomes than the other aspects or the other teaching activities. Hence, how to arrange students’ seats seems quite simple. In reality, we can see that many teachers just make students to sit in nice neat rows. Actually, where students sit has great impact on their behaviours and the learning outcomes. There are various types of seating arrangements for teachers to choose, and different class activities require teachers to arrange students’ seats correspondingly. This paper aims at introducing the following three aspects: the impact of seating arrangement, different types of seating arrangement and the considerations teachers need to take into account when they plan their own seating arrangements. Key words: types impact considerations 2 Seating Arrangement Part one The impact of seating arrangement on students A study of below-average ability Year Nine students seated in fours with pairs of two-seater tables facing found an average of 52% of the time on task. When the seating was put into rows the on-task proportion rose to 84% and then 91%. A similar experiment was tried with sixteen-year-old college students: the on-task rate rose from 64% to 75% when the chairs were changed from three rows to a single semicircle facing the lecture. 1 Also, the following table shows students’ different behaviours due to different seating. 2 Table 1 The times comparison between the last row and the front row Last Row The Second Row Off-task behaviours 55 10 Target Drifting 10 5 Distracted from instruction 43 5 Intention of answering questions 22 48 Answering questions 0 11 Being praised 0 1 Being reminded 0 1 From this table, we can notice that the number of behavioural problems tend to increase as the student sit farther from the teacher and they are more likely to be off task than those close to the front or to the teacher’s desk. They are in the margin of the psychological area of teaching and management, so it is very difficult to attract teacher’s attention. Even if they want to answer questions, they have much less chances. This point is obviously reflected from the table above. In addition, teachers seldom remind and praise the students at the back because they are at the forgotten corner. 1 Michael Marland, 2002. The Craft of the Classroom. 3rd edition. Honorary Fellow, Institute of Education, London University. 2 Zhenghong gen, The issue of back seats, Jiande Educational Bureau, Zhejiang, 2004. http://202.121.15.143:82/document/2005/1/jk050117.htm 3 Seating Arrangement The issue of the back seats is very serious in the big-size classrooms and it exists commonly among different schools. Now, we are emphasizing on the equality of education and many teachers take for granted that our education is equally being carried out because students are in the same classroom, using the same textbooks, having the same teacher and the same learning time for one lesson. But is it the case? Actually, only seating, the seemingly insignificant point, can cause the inequality dramatically. There are some socalled ‘problem students’ nearly in every school. Parents are helpless about them, teachers are annoyed by them, and they are also self-abandoned. However, many people are trying to work out the reasons which cause their misbehaviours, and finally familial and social factors are mainly criticized. Whilst, the issue of back seats, which is possibly the main source of many behavioural problems, is always ignored by almost everyone. Except for the back-seat’s phenomenon, the results of some well-designed research studies show that an increase in physical space between students leads to increased on-task time and decreased disruptive behaviour. In classrooms where students have more space between each other, teachers are even rated by their students as more sensitive and friendly. 3Also, you can use the physical space in the classroom to provide students with additional external control. The most straightforward example is to separate students who cannot seem to stop talking to each other and seat each of them with nondisruptive students. That decreases the negative effect they have on each other and increases the positive effects the nondisruptive students can have on them. Again, separating two students who are arguing may be more effective than either signaling disapproval or standing near them if they are too upset to control themselves when they are so close together. Finally, placing distractible students where there are few distractions or behind a screen or in a cubicle may help them concentrate better.4 The placement of teacher’s desk also affects students’ behaviour. Whether students are in kindergarten or in high school, they will be on-task more consistently and will display less disruptive behaviour when they know they 3 Paine ‘Structuring Your Classroom for Academic Success’, 1983, 25. 4 Herbert Grossman, 2004. Classroom Behaviour Management for Diverse and Inclusive Schools. 3rd edition. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, Inc. 4 Seating Arrangement are closely monitored. 5 In a busy classroom you will see pupils’ eyes flick up to where they expect to see the teacher. Some of the looks will be from pupils wondering momentarily whether to do something silly or not. Others will be from pupils who are deep in their work but want some kind of reassurance. The stable figure of the teacher in a known position in the room is comforting influence for the collaborative enterprise. 6 So we can say that teacher’s desk should be in clear view of all students and many students will choose whether to follow teacher’s instruction or tasks depending on whether the teacher is watching. In China, the traditional seating arrangement reflected the educational philosophy, which emphasizes on facts feeding. So it was very common to see that teacher stood in the front of the classroom, and students sat in rows quietly. This conventional seating arrangement had its own limits undeniably. Firstly, it cultivates students to rely on teachers subconsciously, and teachers become the centre of the classroom naturally. Consequently, students will be very dependent on teachers, and then be quite passive during the teaching and learning activities. Secondly, it is a stereotype that the less able or poorly-performed students sit at the back of the classroom. They are always the forgotten voices, and teachers seem too far away from them. What they are thinking about and how they behave are mostly ignored, which ignite the conflict and resentment towards teachers. Nowadays, the education reform in China requires teachers to get down from the platform and interact with students during lessons. It means that teachers need to rearrange students’ seats and narrow the distance between the teacher and students. 7 Nowadays, the educational approaches are been changing and more and more activities are implemented in the classroom. The increased emphasis on an active role for pupils through discovery and exploratory learning and group work shows itself in the use of different activity areas within the 5 Mary Damer, Seating and Behaviour, July 6, 2000. http://www.illinoisloop.org/md_desks.html 6 Michael Marland, The Craft of the Classroom: a Survival Guide, 3rd Edition. 2002. Honorary Fellow, Institute of Education, London University. 7 http://blog.cersp.com/35897/archive/200604.aspx 5 Seating Arrangement classroom, the use of tables set up for group work rather than for individuals sitting in rows, and relatively free access for movement to and from resource areas. 8 Groups were more likely to use an effective problem-solving strategy when given context-rich problems to solve than when given standard textbook problems. Well-functioning cooperative groups were found to result from specific structural and management procedures governing group members' interactions. Group size, the gender and ability composition of groups, seating arrangement, role assignment, textbook use, and group as well as individual testing were all found to contribute to the problem-solving performance of cooperative groups. 9 Some children work best with their friends, some do not since they are too distracted by talking or playing together. During my three school placements, I noticed that in the first two schools, students have their fixed seats arranged by the teachers, and students in my last school placement can choose their seats by themselves. Mainly and obviously, they are in the friendship groups. I am not sure whether the apparent friendship group are beneficial to every group member, but I think the demerits of friendship group are far more weight than merits although maybe it is more tune with encouraging students’ autonomy, and more likely to gain the goodwill of the pupils if the teacher allow them to find their own places. Some students have already spent so much time in each other’s company in homes, streets, and playground that they just resist teasing each other, joking, and talking. 10 I admit it is friendly, harmless, pleasant, but it is distracting however. Also, the purpose of having groups is to work with each other, teach each other 8 Chris Kyriacou, 1997. Effective Teaching in Schools: Theory and Practice. 2nd edition. Stanley Thornes Ltd. 9 Teaching problem solving through cooperative grouping. Part 2: Designing problems and structuring groups,Patricia Heller American Journal of Physics -- July 1992 -Volume 60, Issue 7, pp. 637-644. http://scitation.aip.org/getabs/servlet/GetabsServlet?prog=normal&id=AJPIAS00006000 0007000637000001&idtype=cvips&gifs=yes 10 Michael Marland, The Craft of the Classroom: a Survival Guide, 3rd Edition. 2002. Honorary Fellow, Institute of Education, London University. 6 Seating Arrangement and learn from each other. Whilst, students within the friendship group are so familiar with each other and their behaviours, personalities and thinking styles are similar to some extent. So I believe that compulsory mixed groups are more beneficial for students, within which they can learn more. If friendship groups are split up, however, this can sometimes lead to resentment, becoming yet one more reason why some children are demotivated and dislike school.11 From what has been discussed above, we can see that gaining and keeping students’ attention and lessening misbehaviours are ongoing challenge for teachers. Workable seating arrangements can help teacher are more readily to monitor students’ activities and make this task easier. 11 Michelle MacGrath, 2000. The Art of Peaceful Teaching in the Primary School: Improving Behaviour and Preserving Motivation. David Fulton Publishers, London. 7 Seating Arrangement Part two Different types of seating arrangement Classroom is far more complex than many teachers think about it. Seating arrangements are with great significance and they are a main part in a teacher’s plan for classroom management. The consideration in arranging students’ seats guarantee teaching and learning can occur as efficiently as possible. 12 Just as Jones 13 said, the best arrangement put the least distance and the fewest barriers between teacher and students. According to James Levin et al, no matter what basic seating arrangement is used, it should be flexible enough to accommodate and facilitate the various learning activities that occur in a given classroom. 14 The teacher needs to be able to walk around the room without the students having to move their desks. Different seating arrangements serve and fit different purposes depending on teacher’s desires. There is more than one way to arrange students’ seats. According to the NATIONAL GUIDELINES FOR EDUCATING EMS INSTRUCTORS, August 2002, the following seating arrangements are suggested: 15 Traditional Lecture Alexandra Ramsden, Seating Arrangements, 1999, 12. http:www.uwsp.edu/Education/pshaw/Seating%20Arrangements.htm 12 13 F. Jones, Positive Classroom Discipline, New York: McGraw-Hill Book Company, 1987. Page. 57-63 14 Classroom management paper, http://www.uwrf.edu/~w1010277/crmpaper.htm#intro 15 Classroom Arrangement Strategies. Appendix VIII NATIONAL GUIDELINES FOR EDUCATING EMS INSTRUCTORS, August 2002 8 Seating Arrangement This is the usual lecture theatre arrangement, mimicking cinemas because the aim is effective one-way communication. The long orientation facilitates sight-lines for video projection, etc. ideal for clear and convincing presentation of images to a large audience; militates against interaction and critical engagement, usually mediated, one-way communication. Theatre style This is the typical arrangement for Senates or Councils, with a focus at the front where speeches are given, but the other participants are engaged in the discussion, and the emphasis is on personal presentation, not mediation through images and text, though this is possible. Ideal for critical engagement between an academic and a relatively large class, with some allgroup discussion, but presentation of text and images is compromised. Circle, Square and Rectangle – Open Circle, Square and Rectangle – Closed 9 Seating Arrangement These two kinds of arrangement are based on the idea of emphasizing communication. Students can see one another face to face, so facial expression, gestures and other forms of nonverbal communication are visible and the communication is enhanced and boosted. Students in this kind arrangement should cooperate with each other. It is easy for students to see each other and discuss. In this situation, the teacher is free to walk around, check students’ work, or sometimes work with the whole group. It is based on the philosophy of collaborative learning. 16 However, this arrangement is not suitable when the teacher is giving a direct instruction because some students have their back to the teacher. Also, students may use most of their time talking about other things instead of being on the task. Partial with Open Area (U-shape seating) This seating arrangement allows the teacher to be in the middle and see all the students as well as have all the students see him/ her. According to Teacher B, this is an effective seating arrangement because it prevents the students from getting distracted with each other since the teacher is in the middle of the class. The U-shape seating arrangement is also good for the fact that students can still help one another because they sit close enough and yet not distract the whole class during a lesson. The problem with this Alexandra Ramsden, Seating Arrangements, 1999, 12. http:www.uwsp.edu/Education/pshaw/Seating%20Arrangements.htm 16 10 Seating Arrangement arrangement is that although the teacher can be in the middle of the room to keep distractions off, at times her/his back could be turned towards the student thus she/he may not be able to see problems if and when they occur. Group Work This kind of seating arrangement is also commonly used by many teachers. In the small groups, the teacher could have four or five students sitting together. With this small group arrangement, the students are able to work in groups easily and share ideas among themselves as well as help each other. Students are expected to use teamwork which gives them the chance to experience what it means to work as a team. Each individual student is able to see what the others are doing and when he/she talks to one person in the group the rest can still hear it. This arrangement is especially good if there are students who are very quiet and are too shy to ask questions because they are afraid of being embarrassed. With this seating arrangement, if students have the same questions, their questions will be answered and the teacher saves time from having to repeat an explanation. Yet, having students sit in small groups can come with some problems. For example, at times the students can get distracted by the other students in the group or they may not be able to see the board as clearly. Also, at times, the teacher can have their back to the students unintentionally and thus may not be aware of everything that’s going on in the classroom. 11 Seating Arrangement Semi-circle arrangement The philosophies of this arrangement can be direct instruction, childcentered or collaborative because all the desks are facing the front of the classroom and all of them can see the board clearly. The teacher can easily move around and supervise every student’s work. Also, it is very convenient for students to have discussion among themselves since they are close to each other. Table rows This arrangement is very convenient and simple because the teacher just needs to place the tables in rows. And this kind of arrangement can motivate students by letting them sit together, work together and share together. It is suitable for problemsolving and social activities. However, some students who sit at the back of the classroom are too far away the chalkboard. It is hard to have class discussion because the students cannot hear each other clearly without moving around to see who is talking. 12 Seating Arrangement Also, there are some other seating arrangements used frequently. The picture in the middle shows the traditional classroom seating arrangement of several rows of desks facing the teacher. Students’ desks don’t touch each other and the teacher only can move from the front to the back, not from side to side. This arrangement is based on the philosophy of teacher-dominated. It is good for the teacher to give direct instruction or for students to have exams, but it is not convenient for group works or some interactive activities. In addition, the students who sit at the back might be involved in the activities less than other. Meanwhile, behavioural problems will occur relatively. 13 Seating Arrangement Part three: the consideration of seating arrangement 1. The consideration of using different teaching activities Different teaching activities determine the type of seating arrangement Most teachers want to adopt different forms of seating arrangements and switch from one to another. Six teachers in one research reported that 17 they switched from one grouping strategy to another as the activities of individuals and groups of pupils changed. However, the changing activities of the day and the fluctuating numbers of teachers in many of the classroom meant that the seating arrangements could be a complex problem. It is better to find the balance between whole class teaching, group work, and individual teaching. In order to strike this balance, one possible solution is to arrange the desks in a square or horseshoe figuration as the basic form of organisation and switch from this to individual, group and whole class teaching as desired. 18 But in China, seating arrangements are very difficult to carry out and they are not very effective for promoting the learning outcomes as the class size is too big. Sometimes, it is very time-consuming to move students into different groups during one lesson. Teaching the class as a whole can maximise teachers’ time for teaching instead of merely monitoring what the students are doing. 2. The consideration of the characteristics of the activities and students’ preferred level of participation (1) The individual work We can easily imagine that people prefer to the position which is relatively far away from others if he/she wants to works alone without interruption. In the classroom, students will choose the seats which are at the end of the classroom, or near the walls or far away from the centre of the classroom if they want to protect their privacy or to do some tasks individually. 17 Robin Alexander, John Willcocks, and Kay Kinder, Changing Primary Practice. The Falmer Press, 1989. 18 David McNamara, 1994. Classroom Pedagogy and Primary Practice. London and New York. Page 66. 14 Seating Arrangement (2) The cooperative work Usually people will sit very near to each other when they are doing some cooperative works for the sake of convenience. Thus, sometimes the teacher needs to place two students who like to work with each other together when he/she is arranging students’ seats. (3) Competitive work People like to choose inner position to sit when the tasks are competitive. By doing this, they can observe others and work out their strategies. When students are involved in some competitive tasks, they prefer to the seats which are opposite to their opponents in order to increase the frequency of eye contact, and then stimulate the motivation of competition. Through the three points above, we can see that seating arrangements in the classroom should combine individual and public/community space together. Usually children in the central area of a conventional box classroom, or facing the teacher in a ring or horseshoe arrangement, participate more. Most evidence suggests that this is due to children making seat choices to match their preferred level of participation. Those who wish to be involved sit centrally; shyer children choose peripheral seats 19 However, there is some evidence that if children are moved, their participation level can be changed, at least over a short period of time. That is to say, a nonparticipating student will participate if he/she is moved into a central area. So the teacher should swatch the seats frequently in order that students can keep their interests of learning and the level of participation. 3. The consideration of students’ abilities In mixed ability classrooms it may be appropriate to group children according to aptitude if teaching is to be matched to their ability. 20 When the teacher arranges students’ seats according to their abilities, he/she cannot get over the fact that students may be very different on many characteristics which may be related to learning, such as social ability, cooperative ability and motivation. 19 Sean Neill, Classroom Nonverbal Communication. 1991. London and New York. 20 David NcNamara, Classroom Pedagogy and Primary Practice. 1994. London and New York 15 Seating Arrangement Let us look at the following table first. Table 2 Percentage of time spent on task-related behaviour by pupils of different ability Above average Average Below average All pupils Minutes Working Routine observed 1,401 63 10 Awaiting Distracted Not attention observed 7 19 <1 1,365 1,109 59 64 9 13 9 8 22 15 <1 <1 3,875 59 11 8 21 1 From this table, we can see that the average ability group spent less time on working and routine activities, and more time waiting for attention or distracted than above and below average groups. Sometimes, it is not a good idea to stream students into level groups, such as top group, middle group and bottom group. On the contrary, the more able students may be enhanced within the mixed ability group because the less able students will turn to them for help and advice when the teacher’s attention is on somewhere else and the homogeneous ability seating arrangements may be detrimental to the learning of children in low ability groups. 21 That is to say, it is better to disperse students randomly over the class if the teacher’s aim is to balance the whole class. 4. The consideration of sex According to Wheldall and Olds’s (1987) studies, the children in one class spent more time on task when they were required to sit with boys and girls side by side with normally segregated tables. In the second class in the same school where children normally sat in mixed tables they were required to segregate; time on task fell, though interpretation of the results is David NcNamara, Classroom Pedagogy and Primary Practice. 1994. London and New York 21 16 Seating Arrangement complicated by the teacher’s increased use of criticism and her change of working practices to include worksheets. Time on task was about 90 percent in mixed groups, and 75 percent or less in segregated groups. 22 Also, one small-scale study raised the on-task proportion of time of a Year Nine class from 76% to 91% after changing the seating from self-chosen same-sex positions to compulsory mixed sex ones. 23 Table 3 shows the differences between the task-related behaviours of boys and girls in the present study Girls Boys All pupils Minutes observed 2,555 2,613 5,168 Working Routine 60 58 59 13 10 11 Awaiting attention 7 8 8 Distracted Not observed 19 <1 23 <1 21 1 From this table, we can see that girls spent more time on working and routine activities than boys, whilst boys were more distracted and spent more time on awaiting attention although the differences were not very great. 5. The consideration of group sizes The group size appears to have exerted an influence on the pattern of students’ task-related behaviour. The following table summarizes all the observation data from sessions where group size was known and recorded. 24 22 Sean Neill, Classroom Nonverbal Communication. 1991. London and New York. 23 Michael Marland, The Craft of the Classroom: a Survival Guide, 3rd Edition. 2002. Honorary Fellow, Institute of Education, London University. 24 Robin Alexander, Versions of Primary Education, 1995. London and New York. Page 117. 17 Seating Arrangement Group Minutes Working Routine Awaiting Distracted Not Size observed attention observed 1 to 3 1,161 62 12 6 20 <1 4 to 5 1,045 60 11 6 23 <1 6 to 20 1,523 55 12 8 24 1 21+ 1,265 62 10 10 17 1 All 4,994 59 11 8 21 1 Table 4 Percentage of time spent on task-related behaviour in working groups of different sizes As the size of the groups increased from one to twenty, students spent less time on working and more time on waiting and being distracted. However, when the group had more than twenty students, the situation changed. Students spent more time on working and awaiting attention, but less time distracted. 6. The consideration of students’ ages Table 5 percentage of time spent on task-related behaviour by pupils of differing ages Minutes Working Routine Awaiting Distracted Not observed attention observed 5+ and 6+ 2,081 58 10 10 22 <1 7+ and 8+ 1,672 59 12 6 21 1 9+ and 10+ 1,415 60 13 6 20 1 All pupils 5,168 59 11 8 21 1 From this table we can see that the two older groups spent more time on working and routine activities, and less time distracted and being waiting. That is to say, the older groups have cultivated the habit of moving from one activity to another without seeking help and guidance. Bennett, Desforges, Cockburn and Wilkinson’s (1984) detailed study found that most interaction among groups of infants was at low level-requesting materials and so on. When children did try to assist each other their help was often misleading. 25 25 Sean Neill, Classroom Nonverbal Communication. 1991. London and New York. 18 Seating Arrangement So when the teacher is planning his/her lesson, more group activities can be adopted for older students.26 While elementary-school students love the occasional seating-chart change and the new perspective it brings to them, secondary students are more territorial and prefer not to have things shaken up after they're used to the routine.27 Older students frequently meet in a room with spare seats, for a subject which they have chosen, and in a much smaller group than a younger class. Also, most pupils in the early and middle secondary years sit next to a friend of the same sex. 7. The consideration of students’ different learning styles Gregorc suggests that students with different learning styles prefer different seating arrangement. Classrooms must accommodate students’ with various learning styles.28 Some learners prefer to quiet and ordered environment, so stable or individual seating might be suitable for them. Another learner needs to have creative and free discussion, so arrange them into groups can stimulate and motivate them most. The third learner works best in the environment which can be rearranged. When the teacher arranges their seats, he/she should consider how to allow them seek for the change of the scenery, the associations and the opportunities. 8. The consideration of dealing with highly misbehaved or distracted students Almost every classroom has one or two highly misbehaved or distracted students, whose behaviours are very difficult to manage during working times. Most teachers just assign this kind of students in the front separated All tables are from: Robin Alexander, Versions of Primary Education.1995. London and New York. 26 27 http://www.dummies.com/WileyCDA/DummiesArticle/id-1893,subcatINDUSTRY.html 28 Seating Arrangement for better classroom management, Paul Denton, Adventist Education, Summer 1992. 19 Seating Arrangement seat in avoidance of their disruption. However, this kind of seating arrangement is not as effective and suitable for controlling students’ behaviour. On the contrary, they will be more and more against teachers, and then lose the interest in learning. Probably, it is a better idea to have one or two desks located in the quietest and most non-distracting location as students’ special ‘office area’. This area to students is not considered as a punishment area but a place where they can work undistracted. Eventually, the teacher will help the misbehaved and distracted students recognize that they can do their best in a quiet place. 29 29 seating and behaviour, http://www.illinoisloop.org/md_desks.html 20 Seating Arrangement Conclusion: Seating arrangements are very important to the classroom management. Whether the seating arrangement is suitable or not determines the students’ behaviours, the teaching effects and the learning outcomes. The way a teacher arrange students’ seats largely depends on the type of the students and the teacher’s philosophy. There are many alternatives for a teacher to choose to arrangement students’ seats. For my part, I believe that there is no best way to arrange the seats because in different situations students behave differently in the class and to each other. Also, students have their own learning styles and preference, so rows might be successful to some students whilst semi-circle could be for the other. As a teacher, we need to plan each seating arrangement carefully and try to take as many considerations as possible into account. 21 Seating Arrangement Reference: 1. Berth Bruno, Classroom Seats More than Meets the Eye. 1998. 2. Chris Kyriacou, 1997. Effective Teaching in Schools: Theory and Practice. 2nd edition. Stanley Thornes Ltd. 3. David McNamara, 1994. Classroom Pedagogy and Primary Practice. London and New York. Page 66 4. F. Jones, Positive Classroom Discipline, New York: McGraw-Hill Book Company, 1987. Page. 57-63 5. Herbert Grossman, 2004. Classroom Behaviour Management for Diverse and Inclusive Schools. 3rd edition. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, Inc. 6. Mary Damer. (July 6, 2000) How seating arrangements impact student behaviour. http://www.illinoisloop.org/md_desks.html 7. Mary Damer, Seating and Behaviour, July 6, 2000. http://www.illinoisloop.org/md_desks.html) 8. Meifeng Wang, Seating Arrangement in the Classroom Management, http://course.ncue.edu.tw/article20new.shtml 9. Michelle MacGrath, 2000. The Art of Peaceful Teaching in the Primary School: Improving Behaviour and Preserving Motivation. David Fulton Publishers, London. 10.Michael Marland, 2002. The Craft of the Classroom. 3rd edition. Honorary Fellow, Institute of Education, London University. 11.Paine. Structuring Your Classroom for Academic Success, 1983, 25. 12.Rookie. Teaching Technique: Choosing a Seating Arrangement http://www.du mmies.com/WileyCDA/DummiesArticle/id-1893,subcatINDUSTRY.html 22 Seating Arrangement 13.Seating Arrangement for Teaching and Learning Spaces. http://www.ists.unimelb.edu.au/ts/classroom.htm 14.Seating Arrangements, http://www.msu.edu/~rosstrac/seating.htm 15.S. Holtrop. Writing lesson Plans: Seating Arrangements, 1997. http://www.huntington.edu/education/lessonplanning/seating.html http://www.snet.net/features/issues/articles/1998/08210101.shtml 16. Teaching problem solving through cooperative grouping. Part 2: Designing problems and structuring groups,Patricia HellerAmerican Journal of Physics -- July 1992 -- Volume 60, Issue 7, pp. 637-644 http://scitation.aip.org/getabs/servlet/GetabsServlet?prog=normal&id=AJ PIAS000060000007000637000001&idtype=cvips&gifs=yes 17. Zhen Hong gen, The issue of back seats, Jiande Educational Bureau, Zhejiang, 2004. http://202.121.15.143:82/document/2005/1/jk050117.htm 23