Elements of Poetry

advertisement

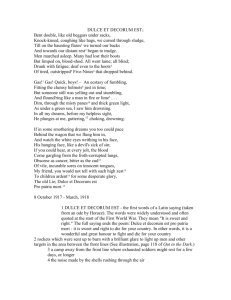

Elements of Poetry What is Poetry? #1 Literature, then, exists to communicate significant experience – significant because it is concentrated and organized. ~ Tennyson, The Eagle (1851) FRAGMENT He clasps the crag with crooked hands; Close to the sun in lonely lands, Ringed with the azure world, he stands. The wrinkled sea beneath him crawls; He watches from his mountain walls, And like a thunderbolt he falls. ~ 1. How is The Eagle “concentrated?” 2. How is The Eagle “organized?” Elements of Poetry What is Poetry? #2 Two limiting approaches to poetry… 1. “looking for a lesson or a bit of moral instruction” 2. “expect to find poetry always beautiful” ~ Shakespeare, Winter (from Love's Labour's Lost, V.ii; written circa 1593) When icicles hang by the wall, And Dick the shepherd blows his nail, And Tom bears logs into the hall, And milk comes frozen home in pail, When blood is nipp'd, and ways be foul, Then nightly sings the staring owl, To-whit! To-who!—a merry note, While greasy Joan doth keel the pot. When all aloud the wind doe blow, And coughing drowns the parson's saw, And birds sit brooding in the snow, And Marian's nose looks red and raw, When roasted crabs hiss in the bowl, Then nightly sings the staring owl, To-whit! To-who!—a merry note, While greasy Joan doth keel the pot. ~ 1. How are the words “merry” and “sing” employed? 2. What is the point of this poem? Elements of Poetry What is Poetry? #3 Poetry takes all life as its province. ~ Wilfred Owen, Dulce et Decorum Est (8 October 1917 - March, 1918) Best known poem of the First World War DULCE ET DECORUM EST1 Bent double, like old beggars under sacks, Knock-kneed, coughing like hags, we cursed through sludge, Till on the haunting flares2 we turned our backs And towards our distant rest3 began to trudge. Men marched asleep. Many had lost their boots But limped on, blood-shod. All went lame; all blind; Drunk with fatigue; deaf even to the hoots4 Of tired, outstripped5 Five-Nines6 that dropped behind. Gas!7 Gas! Quick, boys! – An ecstasy of fumbling, Fitting the clumsy helmets8 just in time; But someone still was yelling out and stumbling, And flound'ring like a man in fire or lime9 . . . Dim, through the misty panes10 and thick green light, As under a green sea, I saw him drowning. In all my dreams, before my helpless sight, He plunges at me, guttering,11 choking, drowning. If in some smothering dreams you too could pace Behind the wagon that we flung him in, And watch the white eyes writhing in his face, His hanging face, like a devil's sick of sin; If you could hear, at every jolt, the blood Come gargling from the froth-corrupted lungs, Obscene as cancer, bitter as the cud12 Of vile, incurable sores on innocent tongues, My friend, you would not tell with such high zest13 To children ardent14 for some desperate glory, The old Lie; Dulce et Decorum est Pro patria mori.15 1 5 10 15 20 25 ~ 1. How do the comparisons in lines 1, 14, 20 and 23-24 contribute to the effectiveness of the poem? 2. What does the poem gain by moving from plural pronouns and the past tense to singular pronouns and present tense? 3. Google the Latin phrase in lines 27-28. What is Owen trying to communicate? DULCE ET DECORUM EST - the first words of a Latin saying (taken from an ode by Horace). The words were widely understood and often quoted at the start of the First World War. They mean "It is sweet and right." The full saying ends the poem: Dulce et decorum est pro patria mori - it is sweet and right to die for your country. In other words, it is a wonderful and great honour to fight and die for your country 2 rockets which were sent up to burn with a brilliant glare to light up men and other targets in the area between the front lines (See illustration, page 118 of Out in the Dark.) 3 a camp away from the front line where exhausted soldiers might rest for a few days, or longer 4 the noise made by the shells rushing through the air 5 outpaced, the soldiers have struggled beyond the reach of these shells which are now falling behind them as they struggle away from the scene of battle 6 Five-Nines - 5.9 calibre explosive shells 7 poison gas. From the symptoms it would appear to be chlorine or phosgene gas. The filling of the lungs with fluid had the same effects as when a person drowned 8 the early name for gas masks 9 a white chalky substance which can burn live tissue 10 the glass in the eyepieces of the gas masks 11 Owen probably meant flickering out like a candle or gurgling like water draining down a gutter, referring to the sounds in the throat of the choking man, or it might be a sound partly like stuttering and partly like gurgling 12 normally the regurgitated grass that cows chew; here a similar looking material was issuing from the soldier's mouth 13 high zest - idealistic enthusiasm, keenly believing in the rightness of the idea 14 keen 15 see note 1 1 To see the source of Wilfred Owen's ideas about muddy conditions see his letter in Wilfred Owen's First Encounter with the Reality of War: On 30th of December 1916 Wilfred Owen, having completed his military training, sailed for France. No knowledge, imagination or training fully prepared Owen for the shock and suffering of front line experience. Within twelve days of arriving in France the easy-going chatter of his letters turned to a cry of anguish. By the 9th of January, 1917 he had joined the 2nd Manchesters on the Somme – at Bertrancourt near Amien. Here he took command of number 3 platoon, "A" Company. He wrote home to his mother, "I can see no excuse for deceiving you about these last four days. I have suffered seventh hell. – I have not been at the front. – I have been in front of it. – I held an advanced post, that is, a "dug-out" in the middle of No Man's Land.We had a march of three miles over shelled road, then nearly three along a flooded trench. After that we came to where the trenches had been blown flat out and had to go over the top. It was of course dark, too dark, and the ground was not mud, not sloppy mud, but an octopus of sucking clay, three, four, and five feet deep, relieved only by craters full of water . . ." Notes copyright © David Roberts and Saxon Books 1998 and 1999. Free use by students for personal use only. The poem appears in both Out in the Dark and Minds at War, but the notes are only found in Out in the Dark. © 1999 Saxon Books. Elements of Poetry What is Poetry? #4 Poetry achieves its extra dimensions—its greater pressure per word and its greater tension per poem—by drawing more fully and more consistently than ordinary language on a number of resources, none of which is peculiar to poetry. ~ A. E. Housman, Terence, this is stupid stuff (1896.) ‘TERENCE, this is stupid stuff: You eat your victuals fast enough; There can’t be much amiss, ’tis clear, To see the rate you drink your beer. But oh, good Lord, the verse you make, It gives a chap the belly-ache. The cow, the old cow, she is dead; It sleeps well, the horned head: We poor lads, ’tis our turn now To hear such tunes as killed the cow. Pretty friendship ’tis to rhyme Your friends to death before their time Moping melancholy mad: Come, pipe a tune to dance to, lad.’ Why, if ’tis dancing you would be, There’s brisker pipes than poetry. Say, for what were hop-yards meant, Or why was Burton built on Trent? Oh many a peer of England brews Livelier liquor than the Muse, And malt does more than Milton can To justify God’s ways to man. Ale, man, ale’s the stuff to drink For fellows whom it hurts to think: Look into the pewter pot To see the world as the world’s not. And faith, ’tis pleasant till ’tis past: The mischief is that ’twill not last. Oh I have been to Ludlow fair And left my necktie God knows where, And carried half way home, or near, Pints and quarts of Ludlow beer: Then the world seemed none so bad, And I myself a sterling lad; And down in lovely muck I’ve lain, Happy till I woke again. Then I saw the morning sky: 5 10 15 20 25 30 35 Heigho, the tale was all a lie; The world, it was the old world yet, I was I, my things were wet, And nothing now remained to do But begin the game anew. 40 Therefore, since the world has still Much good, but much less good than ill, And while the sun and moon endure Luck’s a chance, but trouble’s sure, I’d face it as a wise man would, And train for ill and not for good. ’Tis true, the stuff I bring for sale Is not so brisk a brew as ale: Out of a stem that scored the hand I wrung it in a weary land. But take it: if the smack is sour, The better for the embittered hour; It should do good to heart and head When your soul is in my soul’s stead; And I will friend you, if I may, In the dark and cloudy day. 45 50 55 There was a king reigned in the East: There, when kings will sit to feast, 60 They get their fill before they think With poisoned meat and poisoned drink. He gathered all the springs to birth From the many-venomed earth; First a little, thence to more, 65 He sampled all her killing store; And easy, smiling, seasoned sound, Sate the king when healths went round. They put arsenic in his meat And stared aghast to watch him eat; 70 They poured strychnine in his cup And shook to see him drink it up: They shook, they stared as white’s their shirt: Them it was their poison hurt. —I tell the tale that I heard told. 75 Mithridates, he died old. ~ 1. Housman assesses three possible aids to worthwhile living. What are they? What does Housman consider the best? What six lines best sum up his philosophy? 2. Many people like cheerful and optimistic literature. What is Housman’s view? 3. Why does Housman mention Mithridates as he does?