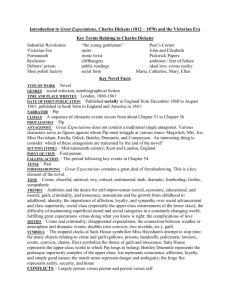

(PIP) and Disability Living Allowance (DLA)

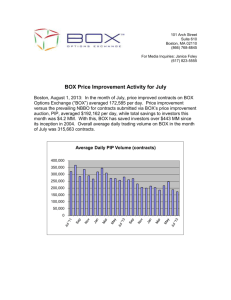

advertisement