UNIVERSITY OF NOTTINGHAM SCHOOL OF HUMANITIES

advertisement

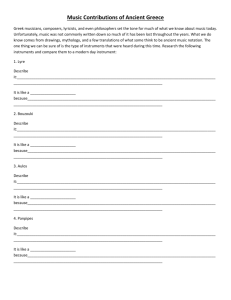

UNIVERSITY OF NOTTINGHAM SCHOOL OF HUMANITIES DEPARTMENT OF CLASSICS Q8D501 Ancient Art and its Interpreters (30 CREDITS) Autumn Semester 2009-10 Katharina Lorenz Lucy Wadeson Important Notes Please note that the information contained in this booklet is provisional. In particular, the dates and times of classes may need to be changed as a result of unforeseen circumstances. It is your responsibility to make sure that you are aware of such changes by consulting the noticeboards on the first floor of the Classics Department, ARCS, regularly. This booklet does not repeat information given in the Department of Classics Undergraduate Handbook (available online at http://www.nottingham.ac.uk/classics/). Everything in that handbook, so far as it is relevant to this module, should be deemed to form part of this booklet, unless explicitly superseded below. 1. Content and Role This 30-credit module covers a deliberately broad range of visual material from the classical world and approaches to this material from antiquity to the present day. Approached via a series of selected themes and visual exempla, the study of this material provides students with the empirical skills and methodologies necessary for research into the visual culture of Greece and Rome and of society more broadly. These complement the research techniques taught in the second core module for the MA in the Visual Culture of Classical Antiquity, namely Researching the Ancient World (Q8D087). 2. Classes Thursday, 16.00 - 18.00 3. Attendance Attendance at all classes is compulsory. If you have good reason for not being able to attend a class, you must inform the convener in advance by email to katharina.lorenz@nottingham.ac.uk or by leaving a telephone message with the Departmental Administrator (0115 951 4800). At each class you will be given work to do in preparation for the following week’s class. If you miss a class, it is therefore essential that you contact the module convener as soon as possible after the class to obtain information about your preparatory work for the following week. 4. Teaching and Study Methods The module consists of 10 seminar sessions. These will be based around discussion of specific methodological aspects vital for the study of ancient visual culture which are explored through a small corpus of objects and monuments. You are expected to contribute fully to these discussions. You are therefore expected to do a significant amount of preparatory reading and thinking before each class, to be able to engage in discussion as well as to be in a position to assess approaches in current research. 5. Assessment This module will be assessed by a piece of written coursework of approximately 5000 words, on a topic to be agreed with the module convener. The coursework should focus on one or more pieces of ancient evidence, and analyse it by testing out current approaches in art-historical research. You are expected to set up your research project independently and discuss it as soon as possible with the module convener, and no later than 26 November 2009 . 2 The essay must be submitted to the Department of Classics Office, via its Essay Box, no later than 12 noon on 12 January 2010. Word length: A variation of 5% in either direction is acceptable (i.e. ranging from 4750-5250 words). A variation of more than 5% is unacceptable: an essay of less than 4750 words will not cover the question adequately, and an essay of more than 5250 words, however good it is, will be PENALISED BY 5% FOR EXCESSIVE LENGTH. When calculating the word-count for your essay, you should INCLUDE FOOTNOTES/ENDNOTES, but EXCLUDE THE TITLE AND BIBLIOGRAPHY. If there is no word-count on your cover-sheet, the marker will estimate the word-count of your essay, and WILL PENALISE THE ESSAY IF IT APPEARS TO BE OVERLENGTH. All essays must be word-processed. It is expected that you attach photocopies / digital images of the objects you discuss to strengthen your argument. Particular care should be given to the structure of your argument, organization of material, to spelling, punctuation, and to the presentation of the bibliography. For general guidelines on the format of your essay, on deadline extensions and submission, see the guidance given in sections 6.1-6.5 of the Classics Postgraduate Taught Course Handbook. Feedback You will receive feedback on your written coursework through a Coursework Feedback Form, which will be placed in your pigeon-hole in the ARCS B7 (The Agora). You should take careful note of these comments, which are designed principally to help you to improve further your writing, argumentative and presentational skills. Plagiarism Coursework must be entirely your own work. You must not quote or paraphrase other authors without due acknowledgement. Failure to acknowledge your sources may lead to your being suspected of plagiarism, that is, the academic offence of seeking an unfair advantage by using other people’s work as though it were your own. Your coursework coversheet will include a declaration, which you must sign, stating that the work is your own and that you have acknowledged all material taken from other sources. 6. 01.10. 08.10. 15.10. Sessions (1) Why study ancient art? SMITH, R.R.R. (2002) ‘The use of images: visual history and ancient history’, in: T.P. Wiseman (ed.), Classics in Progress, Oxford: 59-102. (2) Style and periodisation NEER, R. (1997) ‘Beazley and the language of connoisseurship’, Hephaistos 15: 7-30. BORBEIN, A.H. (1996) ‘Polykleitos’, in: O. Palagia and J.J. Pollitt (eds.), Personal Styles in Greek Sculpture, Cambridge: 66-90. DESCOEUDRES, J.-P. (1994) Pompeii Revisited. The life and death of a Roman town, Sidney: 151-168. NEWBY, Z. (2007) ‘Art at the crossroads? Themes and styles in Severan art’, in: S. Swain et al. (eds.), Severan Culture, Cambridge: 201-249. KGL (3) Critical historians of ancient art – Laocoon as paradigm W INCKELMANN, J.J. (1755) ‘Reflections on the imitation of Greek works in painting and sculpture’, repr. in: D. Preziosi (ed.), The Art of Art History: a critical anthology, Oxford: 31-39. KGL 3 KGL HOWARD, S. (1989) ‘Laocoon restored‘, AJA 93.3: 417-422. STEWART, A. (2006) ‘Baroque Classics: the tragic Muse and the exemplum’, in: J.I. Porter (ed.), Classical Pasts. The classical traditions of Greece and Rome, Princeton: 127-172. BRILLIANT, R. (2000) My Laocoön. Alternative claims in the interpretation of artworks, Berkeley: 50-61, 93-106. TANNER, J. (2006) The Invention of Art History in Ancient Greece, Cambridge: 212-234. ELSNER, J. (2007) ‘Discourses of style. Connoisseurship in Pausanias and Lucian’, in: idem, Roman Eyes. Visuality and subjectivity in art and text, Princeton: 49-66. 22.10. (4) Text and image in ancient art HIMMELMANN, N. (1966, repr./transl. 1996) ‘Narrative and figure in Archaic art’, in: idem, Reading Greek Art, Princeton: 67-102. SNODGRASS, A. (1998) Homer and the Artists. Text and picture in early Greek art, Cambridge: 67-100; 151-163. GOLDHILL, S. AND R. OSBORNE (eds.) (1994) Art and Text in Ancient Greek Culture, Cambridge: 1-11. GIULIANI, L. (2004) ‘Odysseus and Kirke. Iconography in a pre-literate culture’, in: C. Marconi (ed.), Greek vases. Images, contexts and controversies. Proceedings of the conference sponsored by the Center for the Ancient Mediterranean at Columbia University, 23 - 24 March 2002. Leiden: 85-96. KGL 29.10. (5) Reconstructing the ancient viewer OSBORNE, R. (1994) ‘Framing the centaur: reading fifth-century architectural KGL sculpture’, in: S. Goldhill and R. Osborne (eds.), Art and Text in Ancient Greek Culture, Cambridge: 52-84. HEDREEN, G. (2007) ‘Involved spectatorship in Archaic Greek art’, Art History 30: 217-246. ZANKER, P. (1997) ‘In search of the Roman viewer’, in: D. Buitron-Oliver (ed.), The Interpretation of Architectural Sculpture in Greece and Rome. Studies in the History of Art 49, London: 179-191. BERGMANN, B. (2002) ‘Playing with boundaries: painted architecture in Roman interiors’, in: C. Anderson and K. Koehler (ed.), The Built Surface: architecture and the pictorial art from Antiquity to the Enlightenment, Aldershot: Ashgate: 15-46. 12.11. (6) Images and political identity – the case of Athens HÖLSCHER, T. (1998) “Images and political identity: The case of Athens,” in: D. Boedeker and K.A. Raaflaub (ed.), Democracy, Empire and the Arts in Fifth-Century Athens, Cambridge (Mass.), 153-84. SHAPIRO, H.A. (1998) “Autochthony and the Visual Arts in Fifth-century Athens,” in: D. Boedeker and K.A. Raaflaub (ed.), Democracy, Empire and the Arts in Fifth-Century Athens, Cambridge (Mass.), 127-151. FRANCIS, E.D. (1990), Image and Idea in Fifth-Century Greece, London, 1-42. OSBORNE, R. (1998), Archaic and Classical Greek Art, Oxford, 157-187. LW 19.11. (7) Greek art and Roman copies – Brendel and beyond BRENDEL, O. (1979), Prolegomena to the study of Roman art, New Haven, 368 (1) 68-137 (2). HÖLSCHER, T. (2004) The language of images in Roman art, Cambridge, esp. LW 4 Chs. 3, 7, 8, 12. 26.11. (8) Imperial vs. plebeian art W ALLACE-HADRILL, A. (2007) “The creation and expression of identity; the Roman world,” in: S. Alcock and R. Osborne (ed.), Classical Archaeology, Oxford, 355-80. CLARKE, J.R. (2003) Art in the lives of ordinary Romans: visual representation and non-elite viewers in Italy, 100 BC – AD 315, Berkeley, 2-13, 95129, 181-219, 269-275. TORELLI, M. (1997) “‘Ex his castra, ex his tribus replebuntur’: The Marble Panegyric on the Arch of Trajan at Beneventum”, in: D. Buitron-Oliver (ed.), The Interpretation of Architectural Sculpture in Greece and Rome, London, 144-77. ZANKER, P. (1988) The Power of Images in the Age of Augustus, Ann Arbor, 239-263. LW 03.12. (9) Cultural interaction and the urban aesthetic: the interpretation of the cities of the ‘Decapolis’ BALL, W. (2000) Rome in the East, London: 181-197, 246-356, 376-396. BOWSHER, J.M.C. (1987) “Architecture and Religion in the Decapolis: a numismatic study.” PEQ 119: 62-69. BROWNING, I. (1982) Jerash and the Decapolis. London: 11-17, 77-102. BUTCHER, K. (2003) Roman Syria and the Near East, London: 223-269, 289295. LW 10.12. (10) Religious identities? - Jewish and Christian art in the catacombs at Rome ELSNER, J. (2003) “Archaeologies and Agendas: Reflections on Late Ancient Jewish Art and Early Christian Art.” JRS 93: 114-128. FINE, S. (2005) Art and Judaism in the Greco-Roman World, Cambridge: 111, 47-59, 127-129, 135-139. FINNEY, P.C. (1995) The Invisible God: The Earliest Christians on Art Oxford: 99-132; 146-230 (mostly images) FERRUA, A. (1990), The Unknown Catacomb: a unique discovery of early Christian art, Florence: 153-165 (and images throughout) HACHLILI, R. (1998) Ancient Jewish Art and Archaeology in the Diaspora Leiden: 266-273, 275-282, 285-291, 311-378 (Jewish symbols), 432433, 459-464. LW 7. Bibliography Basic handbooks ALCOCK, S. AND R. OSBORNE (ED.) BEARD, M. AND J. HENDERSON BOARDMAN, J. D’AMBRA, E. FULLERTON, M.D. KLEINER, D.E.E. LING, R. OSBORNE, N. PEDLEY, J.G. 2007. Classical Archaeology. London. 2001. Classical Art. From Greece to Rome. Oxford. 1996. 1998. 2000. 1992. 1991. 1998. 2007. Greek art.4 London. Roman art. Cambridge. Greek art. Cambridge. Roman Sculpture. Yale. Roman Painting. Cambridge. Archaic and Classical Greek Art. Oxford. Greek art and archaeology.4 New York. 5 POLLITT, J.J. RAMAGE, C. AND N. RAMAGE ROBERTSON, C.M. SCHUCHHARDT, W.-H. SMITH, R.R.R. STEWART, A. STEWART, P. 1986. 2004 1975. 1990. 1991. 1990. 2003. Art in the Hellenistic age. Cambridge. Roman Art. Romulus to Constantine.4 Cambridge. A History of Greek Art. 2 vols. Cambridge. Greek art. London. Hellenistic Sculpture. London. Greek Sculpture: an exploration. 2 vols. Yale. Statues in Roman society. Representation and response. Oxford. 6