Eco2220Note1.doc

Macroeconomics Lecture Note

J.D. Han

*

King’s College

I wish to acknowledge that this lecture note owes greatly to the macroeconomics I have lear ned from Professor Jack Carr, who has inspired me to take macroeconomics as my professi on. Copyright reserved. No part of this material shall be reproduced without the author’s c onsent.

"Of course, no reasonable man ought to insist that the facts are exactly as I have described them. But that either this or something like it is a true account ...... This, I think, is both a r easonable contention and a belief worth risking, for risk is a noble one......" (Plato, Phaedo ,

II4 d.)

1

Macroeconomics 2 Chapter I. Introduction

Chapter I. Introduction

1. Key Issues in Macroeconomics: What are our interests and goals in Macroeconomics?

Economics is devoted to the betterment of human material welfare. The material welfare is measured best, at the practical level, by the per capita national income, which is equal to the GDP divided by the size of population.

In terms of per capita national income, the optimal situations can be described as follows: (1) The

per capita national income should be high at the maximum potential level at any point in time; (2

) the per capita national income should grow rapidly with minimum inflation, and (3) the national

income should be stable over time.

We may also want a lowest possible rate of inflation and a stable price level as well.

(1) Maximum Potential Income: Full Employment - Short-term Goal

It is ideal if the actual national income approaches its maximum potential. How would we know whether or not the maximum potential is being realized now? One obvious indicator is the rate of unemployment. There is a one-to-one relationship between the unemployment rate and the level of national income: The higher the rate of unemployment, the lower the level of the national income.

The maximum potential national income can be called the ‘Full Employment National Income’ (Y f for its notation). The full employment national income or Y f

does not correspond to the zero rate of unemployment, but to a certain positive figure of unemployment rates. That positive figure of unemployment rate is only ‘Natural’ and the best that we can achieve in terms of employment.

Thus it is also called ‘Natural Rate of Unemployment’. In other words, the Full Employment means a positive figure of the Natural Rate of Unemployment or NRU in a short form (its notation is U

N

).

How do we know when the actual national income is below the maximum potential level? One sign is the existence of unemployment of production factors above and beyond the ‘natural level’.

When capital and labour available are `under-employed', the aggregate income created from the employment of the factor does fall short of the maximum potential income, that is, the Full

Employment (National) Income or the Natural Rate (of Unemployment National) Income.

Under-employment indicates the situation where the actual rate of unemployment (U) exceeds the natural rate of unemployment (U

N

): U>U

N

. The difference between the two unemployment rates is called `Cyclical Unemployment', which points to under-employment. The natural rate of unemployment is some positive rate of unemployment perfectly compatible with full employment, and consists of frictional and structural employment.

Macroeconomics 3 Chapter I. Introduction

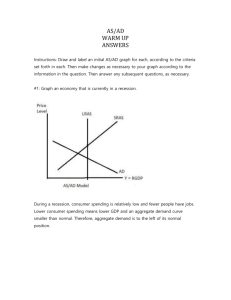

Questions arise as to a) the cause of, b) the duration of and c) the remedy for the under-employment situation where the actual national income is smaller than the full employment income: What prevents an economy from enjoying the maximum potential income? How long would the undesirable situation of the under-employment last? In other words, is the under-employment transient meaning `will be gone', or of equilibrium, meaning `being stuck'? What can be done about the under-employment?

(2) Strong Economic Growth with Minimum Inflation - Long-term Ideal

The performance of per capita national income over time determines the future path of an economy in the long-run. In Canada, the national income evaluated at the current market prices or the market prices of each year grew at an average 10% annum during the ten year period of 1976-1986,

7% of which could be attributed to the simple increases in the prices and the rest to the actual growth of the amount of goods and services. In other words, the rate of the growth of national income in real terms is 3% per annum. This is a strong growth in the light of the size of the

Canadian economy and its advanced stage of economic growth.

(3) Stabilization of National Income - Medium-term Ideal

We would like to have a stable national income over time, having the least fluctuations and deviations from the Long-run Growth Trend. These ups and downs of the national income over time are called, in their entirety, ‘business cycles’. Minimizing business cycles, if possible, is welfare-increasing.

When the government is trying to stabilize the national income, it may use fiscal and monetary policies. The policies are called ‘income stabilization policies’ or ‘activist policies’. Whether the government can eliminate/reduce the amplitude and the duration of business cycles or not is an open question. Keynesians do believe that it is possible, and Classical economists think otherwise.

(4) Stable Price Level: A Low Inflation

Inflation is not just a nuisance. It leads to misallocation of resources, diverting valuable resources

from their best uses. This may not decrease the accounting value of national income. However, it

certainly decreases economic welfares.

The costs of inflation are represented with Menu Cost, and Shoe-Leather Cost, for instance. How ever, innocuous they may sound, they may seriously harm efficient allocation of resources.

Surprice inflation has an additional cost for the society: it helps employers at the expense of employees, and debtors at the expense of creditors.

Macroeconomics 4 Chapter I. Introduction

(5) Trade Off Between Two Goals: Income versus Inflation.

Some economists argue that the above the goal of high income cannot be obtained by a low inflat ion: The two goals cannot be achieved at the same time, and there is an inevitable trade-off betwe en the two.

The level of national income is inversely related to unemployment rates. Therefore, the above arg ument means that a low unemployment rate (meaning a high level of national income) can only b e achieved with a relatively high rate of inflation. As we will see later, this is the idea behind Phil lips Curve.

Inflation

Unemployment

Other economists do not agree with this. They argue that depending on the inflation expectations,

a low rate of inflation and a low rate of unemployment can be achieved at the same time. This w ill be reviewed in terms of “Expectations Augmented Phillips Curve”.

2. Divided House of Macroeconomics Thoughts

In contrast to microeconomics (Price Theory) where there is a general consensus, the macroeconomics has many irreconcilable divisions within its house: There are multiple schools of macroeconomic thoughts, which have quite different, and competing frames of references.

Sometimes they are completely opposite. They tend to disagree on what the most important issues are, let alone what the solutions should be. We are going to review the Keynesian School, the

Classical School, the Neo-Classical Synthesis, the New Classical School or the Rational

Expectations Theory Model, and the New Keynesian School.

For instance, as to the key issues raised above, each school of macroeconomics thought has different views. Suppose that an economy is not achieving its maximum potential national

Macroeconomics 5 Chapter I. Introduction income, or that the actual rate of unemployment is higher than the natural rate of unemployment.

(1) The Keynesian School of Macroeconomics Thoughts

The Keynesian school of macroeconomics was initiated by John Maynard Keynes through his publication of The General Theory of Employment, Interest, and Money in 1936.According to the

Keynesian school, it is the lack of the economy’s aggregate demand that prevents the economy from achieving the maximum potential national income. The ‘cyclical’ component of unemployment rates will not easily go away: Some equilibrating or ‘anchoring’ forces hold the economy down at a level of under-employment. The remedy should be an injection of demand.

Given the bleak prospect of business, which presumably has caused the current recession, it is unlikely that any private economic agents, such as households or firms, will bring an additional demand for the economy: They are all concerned with, and thus constrained by the financial bottom line.

It should be the government that has to bring more demand to the economy. In fact, according to the Keynesian view, the government is able to do so, as it is not constrained by the budget constraint: The government is the only economic agent that can spend more than earn for a prolonged period of times due to its prerogative or sovereign privileges of printing paper monies and issuing bonds.

How about an increase in the aggregate supply ? It would not resolve the recession: The recession was caused by ‘too little demand amid too much supply’. An increase in supply will be just added to inventories, which will put more downward pressures on production processes at the corporate level.

Can we reduce the unemployment with wage cuts ? In fact, all the economists in the 1930swere believed that wage cuts were classical. They believed that workers could not get a job or were unemployed when they demanded too high wages. Thus, they thought that the only solution to the

Great Depression was a wage cut: If wages are cut, and thus the cost of hiring workers is reduced, in the very short run there occur incentives for employers to hire more workers.

However, Keynes disagreed. The above solution is unsustainable. If wage rates are cut, some may get new jobs. More outputs may be produced. However, there will be a reduction in the wages of the previously employed labor forces. The total aggregate wage bills may decrease. If so, there will be less consumption, and thus the newly produced outputs will not be sold. The production should scale down, and the national income falls.

Macroeconomics 6 Chapter I. Introduction

Keynesian Arithmetics: Why wage cuts worsen a recession?

A major component of the aggregate demand is consumption: AE = C (+ I + G + X-M).

The consumption of the workers’ households depend on the component of their income, which is the total wage bills: C = f(Y), and Y = W (+ R + Int. + Profits).The total wage bill for the economy = nominal wage rates (Wage rate) x number of employed workers (#):

When Wage rates go down and # goes up, the product of the two may go up or down, depending on the relative magnitude of a changes in W and a change in #. If

Wage rate (a decrease in the wage rate) exceeds

#, then the total wage bill rises. Thus the consumption goes up and so does the aggregate demand.If

Wage rate (an increase in the wage rate) falls short of

#, then the total wage bill falls. Thus the consumption goes down and so does the aggregate demand.

(2) The Classical School of Macroeconomic Thoughts

On the other hand, according to the economists of the Classical school, as long as there is a well-functioning labor market system without undesirable impediments, a prolonged recession is impossible while certain degrees of short-run fluctuations might be inevitable.

Under-employment of a production factor (such as labor) situation comes from the temporary failure of the alignment of supply and demand of the factor (labor) market. Most commonly, unemployment occurs when some workers are demanding too high a wage rate and thus are not hired by any willing employers. In the absence of any stubborn stupidity of individuals (such as money illusion) and any structural rigidity of the economic system (such as unions), in the long-run as the workers `come to their senses' out of hardship and lower their wage rate to a reasonable level, the unemployment will vanish. Therefore, as long as the functioning of market forces is not hindered, eventually (in the long-run) the national income gravitates to the level corresponding to the full level of employment. The full employment (national) income is the very equilibrium income at least in the long-run.

Student Notes:

______________________________________________________________________________

______________________________________________________________________________

______________________________________________________________________________

______________________________________________________________________________

______________________________________________________________________________

______________________________________________________________________________

______________________________________________________________________________

______________________________________________________________________________

______________________________________________________________________________

______________________________________________________________________________

______________________________________________________________________________

Macroeconomics 7 Chapter I. Introduction

Money Illusion

How many workers are going to work for how many hours (a week) depends on the workers’ motivation. The motivation in turn depends on the reward for work that workers perceive to receive. Note that it does not have to be the actual reward, but the ‘perception of rewards’. If workers somehow do not feel rewarded enough for their work efforts, they would not supply labor forces and would rather go for leisure or unemployment.

The rewards for a worker should be measured by ‘how much commodities or outputs can he purchase with the money wage’: In other words, the labor supply should be an increasing function of real wages .

However, some workers may have some hang-up on a particular value of nominal values for their wages. While they really should pay attention to real wages or real values of their wages, they are erroneously sticking to a certain nominal or money value of wages. This is called ‘money illusion’. The word ‘money’ is the opposite of ‘real (value)’.

In the Keynesian school of macroeconomics, money illusion is an important element in the derivation of its aggregate supply curve.

In the classical school of macroeconomics, ultimately in the long-run, money illusion does not exist.

The short-run fluctuations or business cycles are inevitable. In fact, recessions give a good lesson to undisciplined workers and correct them. They are the periods of consolidation and adjustment for the better. What we can do best to the economy in the short-run is to inform the worker correct and to remove any structural rigidity because both hinder the smooth functioning of the market forces.

Is there any way of increasing the full employment income in the classical model? Yes, in the long-run, there is. The level of full employment income is constrained by the amount of production factors. Even the national income might be at the full employment level, but the actual value is small because the level of the full employment income is low. For instance, suppose that there is a large population yet a small amount of capital in an economy. The scarcity of capital imposes a bottleneck in the production: The low capital-labor ratio means a scarcely equipped worker having a low productivity of labor. The national income is stuck low at the `low' full employment of the existing capital and labor. It is not too difficult to imagine an economy where workers are fully employed, tinkering all day long with poor equipment, for a pittance. The situation is a kind of `low level equilibrium.'

According to the classical school of macroeconomics, the level of the full employment income can

Macroeconomics 8 Chapter I. Introduction be raised with a breakthrough in the availability of production factors. If the amount of capital increases or there occurs an innovation of capital-saving technology, the workers' productivity will rise to bring larger wages. The level of the full employment national income will rise.

3) Differences between Classical and Keynesian Schools

This disagreement between the two schools is highly politicized in the realm of policy issues. They do have fundamentally different views on the role of government in the economy: Except for some monetarists (to whom the author belong), it is generally accepted that a government's expansionary monetary or fiscal policy will increase aggregate demand. However, the rightward shift of the aggregate demand curve may bring different impacts on the price level and the national income depending on the shape and configuration of the aggregate supply curve.

In other words, Keynesian and Classical schools do operate on different assumptions of the aggregate supply conditions. In the Keynesian School, there is a positive economic role for government: Expansionary fiscal and monetary policies which shift the aggregate demand to the right will bring about and increase in real national income without any increase in the price level.

In the Classical school in its alliance with fiscal and monetary conservatives, it is argued that the lasting impact of the increased AD due to an expansionary monetary or fiscal policy is only inflationary.

This difference in political implications comes from the different assumptions of the supply cond itions. Keynesians assume that the Aggregate Supply curve is horizontal or relatively flat. What does the horizontal supply curve mean? It means that the (aggregate) supply (of all the goods an d services) increases greatly in response to a very small stimulus of an increase in the price level.

In other words, the aggregate supply is infinitely elastic with respect to the change in the price le vel.

Recall that in microeconomics the price elasticity of supply measures the increase of supply in response to a unit price rise.

Macroeconomics 9 Chapter I. Introduction

For a given increase in price, the responsive increase in supply is relatively small in Case I: the supply is inelastic with respect to price. For the same increase in price, the resultant increase in supply is relatively large in Case II: the supply is elastic with respect to price. The first case is close to the assumption of the Classical school and, the latter to the Keynesian aggregate supply curve.

Why is the aggregate supply assumed to be elastic in the case of the Keynesian school? The

Keynesian economics came out during the Great Depression when there was a lot of unemployed workers and idle capacities. In the face of a rising price of output, entrepreneurs could easily increase production and supply of output without substantially raising the costs of hiring production factors. This means that the supply could be so easily expanded, and was very responsive and elastic with respect to a rise in output prices: the supply curve was in fact almost horizontal.

With this configuration of the supply and demand curves, only the shift of the aggregate Demand curve will bring about an increase in the equilibrium national income. Put differently, when a government is engaged in expansionary monetary policy (by increasing money supply [MS

]) or/and fiscal policy (by increasing government expenditures [G

] or cutting taxes [T

]), the resultant increase in the aggregate demand shifts the aggregate demand curve. It will bring about only benevolent impacts on the economy: the national income rises while the price level remains unchanged. The rigidity of the general price level is the cornerstone of the Keynesian theory.

The Classical school consists of many branches, but they all basically assume a vertical aggregate supply curve for the economy. For instance, the Monetarists belong to a branch of classical school largely attributed to Milton Friedman. They argue that there are two kinds of the aggregate supply curve. The long-run Aggregate Supply curve is vertical while the short-run Aggregate Supply curve may be positively sloped. In the long-run, as all production factors are more or less fully

Macroeconomics 10 Chapter I. Introduction utilized in the economy in its own way. An increase in the price of outputs does not lead to any increase in production. The aggregate supply curve is vertical at the full employment level. The vertical AS curve implies that it is impossible to increase the equilibrium national income only by increasing the AD.

With the given configuration of the aggregate supply and demand curves, expansionary monetary policy (increasing money supply [MS

]) or/and fiscal policy (increasing government expenditures

[G

] or cutting taxes [T

]) increases aggregate demand [AD

] and shifts the AD curve. It will bring about only a rise in the price level.

P P AS

P *

0

E

0

E

1

AD'

AD

AS

P *

1

P *

0

E

1

E

0

AD'

AD

Y*

1

Y*

2

Y

Y* = Y f

Y

In this situation, only a (rightward) shift of the aggregate supply curve can bring about an increase in the equilibrium national income. In this case, the equilibrium national income is also the full employment income. It may be timely to be reminded of what the major production factors are: capital, labor, and technology. Therefore, only an increase in the stock of capital, an increase in labour force, and technological innovations can lead to an increase in national income. If the government is going to increase the national income, it has to focus on the breakthrough in the supply side. Its economics focuses on the Supply Side. It has to be the “Supply Side of

Economics”.

Macroeconomics 11 Chapter I. Introduction

4) Neo-Classical Synthesis

The Neo-Classical School is a synthesis of the Keynesian and Classical ideas. It adopts the

Keynesian aggregate supply (horizontal) curve for the short-run and the Classical aggregate supply

(vertical) curve for the long-run. Thus the Neo-classical AS curve has upward sloping and vertical segments. Therefore, an increase in the AD leads to an increase in the national income in the first range, a simultaneous increase in the national income and the price level in the second range, and an increase in the price level in the last range.

5) New Classical School of Macroeconomics: “Rational Expectations Theory”

As we might have noted, there is no obvious presentation of the short-run fluctuations of income in the classical model. The New Classical Macroeconomics or Rational Expectations Theory is the most recent offspring of the Classical school. It has come up with exposition of short-term fluctuations in terms of expectations failures. In short, it states that only unanticipated changes in the Aggregate Demand (AD) leads to short-run fluctuations of the national income .

Macroeconomics 12 Chapter I. Introduction

The theory adds Expectations Augmented Aggregate Supply Curve (EAS hereafter) to the classic al model. This EAS curve moves around as the public's expectations as to the price level which i n turn depends on the aggregate demand:

When shifts of the AD are anticipated/expected (to bring about changes in the price level), the EAS shifts up simultaneously to nullify any impact on the equilibrium national income. The path of motion is given along the vertical AS curve in the first panel below. For instance, as long as it is fully expected, any government policy which results in an increase in the AD will not have any impacts on real variables such as real wages, level of employment, and real national income: When a rise in the price level is expected, the workers and entrepreneurs will revise their expectations about the price level and rewrite the wage contract to reflect the increase in the money wages.

Proportional increases in the price level and the money wages lead to the constancy of real wages and all other real economic variables.

This is called the “ Policy Invariance Theorem

” or “

Policy Ineffectiveness Theorem

”: Any anticip ated (monetary) policy does not have any impacts on real variables such as real national income.

This is the major criticism of so-called “Activist Monetary Policy”, which advocates the use of m onetary policy to stabilize the national income. The Policy Invariance Theorem suggests that as l ong as they are fully announced, monetary policies do not achieve the intended goal.

Only unanticipated shifts of the AD curve will not be accompanied with shifts of the AS curve.

Wrong expectations can happen in the short-run: over-expected, under-expected or unanticipated events may occur. In this case, the AD shifts without the offsetting shifts of the short-run AS curve.

This leads to temporary deviations of national income from the full employment level. However, in the long-run when expectations catch up with the reality, -unless another unexpected events involving the AD happen- in any case the EAS will eventually shift by the same amount and in the same direction of the AD curve to nullify the short-term deviation. The path of motion is given as

1 to 2, and to 3 in the second panel below.

Anticipated Changes in AD:

No changes in Y

*

Unanticipated Changes in AD:

Changes in Y

*

in the Short-run;

In the Long-run Y

*

= Y f

Macroeconomics 13 Chapter I. Introduction

6) New Keynesian School of Macroeconomics

The New Keynesian school tries to explain fluctuations of national income in terms of structural rigidifies such as long-term non-indexed labor contracts. Most wage contracts cover a multiple number of periods and do not have the clause of escalating the money wages along with inflation.

In this model the wage contracts are signed on the basis of ex-ante expectations as to the future price level. Once the contracts are signed, nothing can be done about the wage in response to changes in the AD situations and the price level. Unexpected changes in the price level result in changes in real wages, employment, and real national income.

7) A Pendulum of the History of Macroeconomic Thoughts

The above investigation suggests that the Keynesian school focuses on the demand; and that the

Classical school focuses on the supply.

Let’s put these macroeconomic theories in historical perspectives: The historical progression of economics theories mirrors changes in an actual economy, with a time-lag. The most pressing economic concern of the time called for a new frame of reference which suggests a new solution for the problem. Each theory, to a large extent, is the child of times. And as the times change, the theories change.

In the pre-industrial age, the greatest economic concern was the bottleneck in production, or the shortage of the supply of goods and services. It was best epitomized in the famous `Malthusian

Apocalypse': the growth of production (of food) would never catch up with the increasing demand

(for food) propelled by a growing population. Therefore, excess demand or general famine seemed inevitable. Naturally, the focus of economics was on how to make a breakthrough in production or supply. For instance, Adam Smith extolled the benefit of the division of labour, specialization, and scales of economy in production.

Macroeconomics 14 Chapter I. Introduction

The bottleneck on the supply side was removed by the Industrial Revolution which accelerated innovation and technology in production. The demand also grew: the territorial expansion of imperial powers brought markets that created an increased demand for production. In the early twentieth century, however, market expansion reached its limit. There occurred signs of general glut, or of supply exceeding demand.

On October 24, 1929 the precipitous crash of the New York Stock Market triggered the Great

Depression. Unsold goods piled up. Physical capital, equipment and human capital was the problem. The second part of the problem is called `unemployment'. Unemployment was the key social issue. It was regarded by the classical school as a necessary adjustment period of `cooling down' after a century of dashing expansion and growth on the supply side. However, Keynes regarded the depression as a rising from the lack of purchasing power, or effective demand. As there were idle capacities, the supply curve was not a problem: the production could increase very easily with just a small stimulus. The larger the demand, the higher the equilibrium national income level becomes. For instance, in order to increase in national income, consumption and spending should be encouraged. Thrift, which leads to a smaller consumption and thus a smaller demand, should be discouraged as a vice. This contrasts with the fact that thrift is a virtue and a way of achieving prosperity at the level of individuals. What is true of individuals is not necessarily true of the society as a whole. Keynes pointed out the fallacy of composition in savings or thrift, and called it the `Paradox of Thrift.'

In addition, in order to ensure the stability of income, Keynes came up with the so called

`Aggregate Demand Management Policy'; He argued that the investment demand is the major source of fluctuations of the equilibrium national income and thus too volatile to be trusted with the private sector. So semi-autonomous institutions not based on profit principle should be created to be in charge of the aggregate demand management.

The Keynesian economics was transplanted in the experimental farm of the American New-Deal policy. It became a sort of hybrid by being merged with some classical economics into so-called

`Neoclassical Synthesis'. Behind this marriage was the social atmosphere of the time: the original policy recommendations by Keynes were modified to be acceptable by the Americans. For instance, the `Aggregate Demand Management Policy' by a semi-autonomous institution was too suggestive, of a planned economy or a George Orwellian authoritarian society, for the Americans to swallow. So the new eclectic policy recommendation was made that government should intervene in an economy only when there is overheating or over cooling of economic activity, or in other words, when there occurs a deviation of the economy from the long-run trend. That is called

`Counter-cyclical Policy' or `(Income) Stabilization Policy'. Subsequently, it gained a wide acceptance particularly in the post-war United States and the world.

Up until the 1970s, on the basis of the Keynesian principle the government was freely engaged in the `fine-tuning' of the economy. The end result was increased spending which led to the development of an inflationary trend. The policies designed to counter inflation then smothered the private production sector.

Macroeconomics 15 Chapter I. Introduction

The resultant combination of high inflation and high unemployment, or stagflation, could not be resolved within the Keynesian frame of reference.

Here came the Monetarists represented by Milton Friedman who reemphasized the basic tenet of the classical school: "There is no such a thing as a free lunch." The aggregate demand management policy ultimately cannot increase the national income in the long-run. The real national income cannot be increased at no real cost through gimmick policies: Increases in production factors, such as capital stock (K), labour inputs(L), and better Technology(T) should shift the AS curve in order to have a lager equilibrium national income. Capital stock can increase only when the citizens save by practising thrift and the increased savings are channelled into a larger amount of investment.

`Toil and labour' is required to increase the labour input. `Ingenuity' should be encouraged to facilitate technological innovations. The government has no direct control over these variables of the supply side.

He goes one step further to suggest that government policies can possibly do more harm than good.

The time-lag of policies severely limits the economic role of government. For instance, there should be a `rule' as opposed to discretion in money supply, so that the government cannot arbitrarily resort to the increase in the money supply to finance its deficit.

New Classical economics or the rational expectations theory emerged in the 1970s. They shared policy views with the Monetarists. The market consists of rationally forecasting and behaving ind ividual economic agents, and works best if being left alone. The basic tenet is the `Policy Ineffec tiveness Theorem' that anticipated government policies are ineffective without any impact on real

macroeconomic variables such as real national income or investment: anticipating economic age nts.

Macroeconomics 16 Chapter I. Introduction

Chapter II. National Income Accounting

Now this is the time for some tedious, yet important, number crunching.

Our macroeconomic goals have been expressed in terms of national income.

How to calculate the national income?

What determines the level of national income as we have?

1. The Theoretical Part of the National Income Accounting System

1) Supply Sides of National Income

(1) Income Approach

There are two aspects of national income: How it is created, and how it is disposed of. i) Creation of National Income

The National Income with its notation of Y is the sum of the incomes of all the households/individuals. The categories of income are a) labor income such as wages and salaries

(W), b) investment income such as rents (R) and interest payment (Int.), c) profits (P) claimed by entrepreneurs. They are the payments for the production factors (Factor Payment) engaged in production, which are not explicitly shown but implied in the above table:

National Income or Y = W + R + Int. + P = Factor Payments ........(1)

The source of the Factor Payments/Costs and Profit is the Value-Added, which is equal to Total

Revenues minus Material Costs. At the aggregate level, VA is the sum of the net increase in values over material inputs in all industries:

Value Added = Total Revenues – Material Costs ........(2)

Total Revenues from the sales of final goods are equal to Total Production Costs plus Profit: TR

= TC + P.

The Total Production Costs can be broken down roughly into the Costs of Materials(MC) and the

Costs of hired Factors(FC: Factor Payment minus Profit):

TR = MC + FC + P = MC + Factor Payment ........(3).

Therefore, from (1) and (3.b), we get

Y = W + R + Int. + P = VA = Factor Payments.

Note that not all incomes at a personal level are to be included in the national income. The only personal income, which is the factor payment or the reward for participation of production process, is qualified to be included in the national income. For instance, pension income has no counterpart

Macroeconomics 17 of production, and is not to be included in the national income.

Chapter I. Introduction

National Income versus Personal Income

The National Income is not simply a sum of incomes of all individual residents of the economy.

Personal income consists of two parts; one is earned income, and the other is given or transferred from others' earned income. The first is a part of national income, and the second not. For instance, out of the Gross National Income (= W + R + I + P), some portion will not come to individuals: Depreciation does not go for consumption by individuals. Part of Corporate Profits will remain undistributed in the firms to become UDCP (Undistributed Corporate Profits).

Corporate Profits taxes (CPT) will go to government. In addition, there are some personal income items which are not earned -so they are not part of National Income, but are simply given to individuals: Transfer payment (TR) and Interest payment on bonds (IB).

(Aggregate) PI = GDI - D - UDCP - CPT + TR + IB.

Personal Disposable Income is after-tax income for individuals:

PDI = PI - Direct Taxes.

The PDI is not equal to the National Income, but plays an important role in the determination of consumption: PDI is the major determinant of households' consumption decisions. ii) Disposal of National Income

With income, first you pay taxes, and then you spend on goods and services. The latter is

Consumption Expenditures. Then, any left over will be saved: Savings.

Y = C + S + T

(2) Output Approach

Another way of measuring the national income is getting the total value of the goods and services produced as the result of the above production process.

Frequently, we use GDP or GNP to measure this aspect of national income.

The GNP or Gross National Product is defined as

(a) the total market value

(b) of final (excluding intermediate) goods and services

(c) produced (not only sold but also added to inventory)

(d) by the citizens of an economy

(e) for a year (within a current year).

The GDP or Gross Domestic Product is defined as the total market value of final goods and

Macroeconomics 18 Chapter I. Introduction services produced in a country for a year.

First, let’s explain why only final goods and services are included :

For the above economy, in calculating the GNP, we count only $ 25, not $ 55. Here the principle is to count the value of every good but once. The problem of double-accounting is counting the value of some outputs twice or more. The values of the material inputs or intermediate goods should not be counted separately once the values of final goods which use them as ingredients are counted.

When we take account of final goods, we are taking the value of intermediate goods, which make up the final goods, into account. Counting the value of intermediate goods separately in addition to final goods leads to double counting.

Double Counting in the National Income Accounting System:

Problem of double counting is the most serious with government sector. According to the

Output approach, the value of final goods and services produced by the government should be included.

Since there are no markets where government goods and services are bought (or evaluated), the value of goods and services produced by government or `public goods' are evaluated at their production costs. Subsequently, the value on the basis of cost is included in the national income.

Whenever government makes expenditures to produce some goods and services, the national income accounting system simply assumes that there occurs an increase in national income by the amount of government expenditures; all government expenditure is assumed to be on final goods. The very problem blurs the distinction between final and intermediate goods in the government sector.

Second, what does it mean by “by the citizens of an economy”:

If all the goods and services produced by the citizens or the nationals are summed up, the result is

Gross National Product.

If all the goods and services are produced by the residents, national or non-national, the result is

Gross Domestic Product.

Macroeconomics 19 Chapter I. Introduction

GDP versus GNP

The difference is created by the foreign and overseas investment.

Some countries have many citizens as well as their capital (money) working overseas. In this case,

GNP is larger than GDP. Japan and Holland are good examples. Kuwait is another example where a lot of her citizens doing business and residing in foreign countries.

The countries, which take a lot of foreign investment, should have GDP larger than GNP; not all of what is produced in the countries is necessarily produced by the national. Canada belongs to this group.

The difference between GDP and GNP is the net factor payments to foreign residents , who have contributed production factors, such as capital, labor, and management skills to the domestic production.

Third, the only goods and services produced within the current year are included:

Last, but not least, what if there are no market prices? Certain goods and services do no go through the market and thus they do not carry any prices.

The goods and services produced by the government or public goods should be included in the

National Product. There arises a question of how to come up with the market value of public goods? How to include the value of the Gibbon's park service on Sunday? How about an hour of lecture delivered by a professor? How about national defence by the military forces?

There is no market or market price for any of these public goods. So the National Income Account calculates the value on a cost basis: The operating costs for the park service are its value. The total costs incurred in creating an hour of a university lecture are the value of the educational session that enters the national income accounting. Therefore the value of public goods is equal to their cost of production.

In this method, we are measuring the National Product(NP) or the Aggregate Output (YS) while

Method I focuses on the National Income (NI or Y as a shorter abbreviation). It is found that in this simple economy, without government or foreign sector, the National Income, obtained in Method

I, is equal to the National Product in Method II at all times:

National Income = National Product;

Domestic Income = Domestic Product;

Aggregate Income = Aggregate Product, or

Y = YS at all times.

Macroeconomics 20 Chapter I. Introduction

If a $ 1,000 billion or $1 trillion of national income is created in the economy, then aggregate outputs of the same amount must be produced newly in all industry in a year.

In sum, the supply side of the national income is

W + R + Int. + P = Y = C + S + T

(Creation) (Disposal)

Can you express Y = YS graphically?

Put Y on the horizontal axis;

Put YS on the vertical axis;

Draw the line with an angle of 45 degrees – Remember a 45 degree line has the slope e qual to one.

YS

YS = Y

4 5

0

Y

2) Demand Side = Expenditure Approach

Method III: Expenditure Approach)

We have so far focused on the supply side in the circular flow of goods and services in an economy.

The value of supply of final goods and services is equal to their value of demand.

In a general economic model, who demands goods and services?

Consumers, firms, government, and foreigners.

The value of demand for an entire economy or is the sum of expenditure or Aggregate

Expenditures (AE) on all the domestically or nationally produced goods and services. They consist of the following demands: First the expenditures by the consumers is called ‘Consumption

Expenditure’ with the notation of C; the demand by the firms is called ‘Investment’ with the notation of I; the demand by the government is called ‘Government Expenditures’ with the

Macroeconomics 21 Chapter I. Introduction notation of G; and the demand by the foreigners is called “Exports’ with the notation of X.

The sum of these expenditures is the Aggregate Expenditures: AE = C + I + G + X.

Two important points should be made:

Why C + I + G + X – M?

First, for the accounting simplicity, in reality the statistical data of C, I and G include the components of foreign goods and services. For instance, you must know how much is the total amount of your annual consumption. However, can you break the total amount into the expenditures on the domestically produced goods –made in Canada- and the foreign made goods?

Probably, we cannot do that at the individual level. So, C, reported or collected, must contain the expenditures on the domestic as well as the foreign (made) goods and services.

As the Aggregate Expenditures are on the domestically made or the nationally made goods and services, the foreign components should be subtracted. Although we do not know our individual expenditures on foreign goods and services, the total expenditures on the foreign goods and services, which are made by all the civilian households, firms and government agencies, can be captured by the customs office in its aggregate data of Imports (with the notation of M).

Therefore the aggregate expenditures on the purely domestically produced goods and services are equal to C + I + G + X

– M.

The difference between the Ex-ante and Ex-post Aggregate Expenditures

Second, there are the ex-ante aggregate expenditures and the ex-post aggregate expenditures.

There are two different kinds of demands or expenditures depending on whether or not the expenditure or demand is planned ahead of time.

The difference between the ex-ante and the ex-aggregate expenditures is Inventories. Inventories are goods which are not demanded now and thus carried over the next period. In a sense, as the firms would not throw these inventories away, the inventories are regarded as ‘being demanded by the firms themselves’. Obviously, this part of demand or expenditures was not planned at all by the firms, but in fact is made after the unfolding of the unfortunate result of planned expenditures falling short of supply. In this sense, it is ex-post (after the event) demand. This part of expenditures on inventories by the firms is regarded as ‘ part of Investment for the future sales’, and thus is to be included in I.

In sum, ex-ante I + Inventories = ex-post I, or

AE ex-ante = C + planned I only + G + X – M: only sold part of aggregate products is included.

AE ex-post = C + planned I + unplanned I or Inventories + G + X: all part of aggregate product is included.

Macroeconomics 22 Chapter I. Introduction

What about the Depreciation of Captial?

Investment is the sum of net investment and depreciation (allowance). Depreciation is capital consumption or wears and tears of capital stock. Allowances are needed to maintain the constant level of production capacities. Capital Consumption Allowances and depreciations are different names for the same thing:

Net Investment = Gross Investment - Depreciation

This depreciation makes difference between the Net and Gross concepts of National Income or

Product:

Net National Product = Gross National Product - Depreciation;

NDP (Net Domestic Product) = GDP (Gross Domestic Product) – Depreciation

These Net concepts of national income or national product may measure the total amount of outputs available for consumption and investment above the maintenance of the present economic level. Thus they give us an idea of what is available for consumption. Deprecation Allowances of the National Income should not be consumed away. Therefore, if we are interested in a national income as a measure of the standard of living or, we must look at the Net concept of National

Income or Product.

Elusive concept of Deprecation and Capital

In reality, however, we do not see any international comparison of national income done with NDP (Net Domestic Product), NNP(Net National Product) or any Net concept of national income or product.

The reason for this lies in the difficulties in measuring the wears and tears of capital. More fundamentally, the main problem is defining capital in the first place; what is capital? It involves a fair amount of ambiguity to draw a line between durable and non-durable goods.

Usually, all goods that have a life longer than certain duration will be treated on a capital basis, their wears and tears are regarded as capital consumption. On the other hand, the goods that have a life span shorter than this duration will be treated on an inventory basis and their using up is treated as a cost of production. The dividing line is intrinsically arbitrary.

Each country could have different tax regulations concerning the allowances for capital consumption. The `magic number' happens to be 3 years in Canada now. This amount of depreciation (capital consumption) depends crucially on the above rule of defining what constitutes capital. The Net Domestic Product is an economically more meaningful concept than GDP, but because of the difficulty in measuring depreciation GDP is used.

Macroeconomics 23 Chapter I. Introduction

3) Equilibrium National Income: Circular Flow of National Income

It is established that Y

YS = AE ex-post in reality at all times. The equalities are of identity: they are trivially equal to each other at all time, i.e., at the equilibrium as well as at the disequilibrium.

However, Y = YS = AE ex-ante only at the equilibrium.

Of course, Y = YS = AE ex-post.

And at the disequilibrium, (Y = YS)

AE ex-ante.

Still Y = YS = AE ex-post.

Let’s have some numerical examples which illustrate the difference between the ex-ante and the ex-post Aggregate Expenditures:

Suppose that there is only one demander, and there is one supplier in the economy. They meet each other only once a year on the market day.

Prior to the market day, the demander will come up with how much he would like to purchase on the market day. The amount, say $100 billion, is the planned or ex-ante demand or expenditure.

On the other hand, the supplier guesses how much the demander will purchase, and produces outputs. Suppose that the total amount of the outputs is $120 billions.

On the market day, the supplier and the demander reveal each other’s figure at the market.

Obviously, it turns out that the demand falls short of the supply by $ 20 billions. There will be $ 20 billion worth of products left over at the end of the day. They are not going to be left on the market.

They will be taken back by the supplier for future sales. Who demands these inventories? The producer. Under what category? Investment on inventories, but they are unplanned or ex-post

(after the market day) demand.

YS = Y = 120, and ex-ante AE = 100.

Thus,

YS > AE ex-ante

.

This is a disequilibrium.

How much will be the production level for the next year, assuming that the AE level will remain constant? The producer will produce only $ 80 billions so that the supply will be equal to the demand at $ 100 billions. That is how much income is going to be created: for the next year, Y =

YS = $ 80 billions. You note that Y will decrease as S > D or YS > AE.

In this case, the total ex-post demand is the sum of the ex-ante demand of $100 billions, which has

Macroeconomics 24 Chapter I. Introduction been planned, and the unplanned demand or inventory accumulation of $ 20 billions. Thus, the total ex-post AE = 100 + 20 = 120, which is equal to the supply. The unplanned AE will always fill the gap between the ex-ante AE (Demand) and the supply.

Now we are not going into specific mathematical equations for the aggregate expenditures. We will cover them in the next section. However, in general what kind of AE curve are we looking for the equilibrium?

Recall that the supply side of national income gives the curve Y = YS which is a 45 degree line.

The equilibrium means the intersection of Supply and Demand curve. The demand side curve or

AE curve should be sloped less than at 45 degrees, and should have some positive vertical intercept.

S

D = AE

What kind of individual components of expenditures would lead to this Aggregate Expenditure curve? We will examine them in the next section.

Let's sum up:

-National Income: W + R + Int. + P = Y = C + S+ T

-Aggregate Output or National Product: YS =

P market

x Q final

-Supply Side: Y = YS at all times.

-Demand Side: ex-ante AE = C + I + G + X –M

ex-post AE = C + I + Inventories + G + X – M

-Equilibrium: Y = ex-ante AE in equilibrium.

C + S + T = C + I + G + X –M

S + T + M = I + G + X ↓ ↓

Leakage Injection

Macroeconomics 25 Chapter I. Introduction

This equality can be well illustrated with the following Circular Flow Chart :

Note: The following Leakages (S and T) and Injections (I + G) should be explicitly written on the

above corresponding arrows:

For Financial Intermediaries = Banks, the leakage is S(saving) to the right of the above graph, and the injection is I(investment funds provided by banks) to the left of the above graph.

For Government: In this case, the leakage is T(tax) to the right of the above graph, and the injection is G(government expenditures) to the left of the above graph.

4) Applications of the Equilibrium Condition for National Income

(1) Principle

Ex-ante (meaning that we exclude Inventories from the Aggregate Expenditures)

As we can see in the above chart, the injection combined together (I + G + X) is not necessarily equal to the leakage put together (S + T + M). The investment here is the planned one. Only when they are equal to each other, there is an equilibrium, where the current level of flow of the national income persists.

When the injection is larger than the leakage (I + G + X > S + T + M), the flow levels up and the national income rises.

Ex-post (meaning that we include Inventories in the Aggregate Expenditures)

I + Inv + G +X = S + T + M at all times, at both equilibrium and disequilibrium. The total

Macroeconomics 26 Chapter I. Introduction investment is the planned investment I plus the unplanned investment, i.e., inventory accumulation.

(2) What do we actually see is the ex-post aggregate expenditure.

The statistical book of the National Income Accounting reports Investment as the sum of the planned I and inventory accumulation: The investment reported in the NIA is the ex-post aggregate expenditure. Thus, the Y=YS = ex-post AE: The three aspects of the national income are equal to each other.

Thus, in the statistical book, the supply is equal to the demand. However, the demand is the ex-post one. Thus, the equality of the supply and the demand does not mean that the economy is at the equilibrium and the national income will persist at the present level.

(2) Applications: i) “Twin Deficits”

The condition for the equilibrium national income is ex-ante I + G + X = S + T + M .

In economics, we assume that the economy gravitates to this equilibrium condition: related economic variables do change in the way to bring about the equilibrium.

We can re-arrange the equilibrium condition for national income as

I - S + G - T = M –X.

I – S is the investment in excess of savings; G- T is government expenditures in excess of tax revenues, or in a word, government budget deficit ; and M-X is exports in excess of imports and thus international trade deficit .

If the part of I-S is held constant, an increase in the other left-hand side variable, G-T or government budget deficit, leads to an increase in the right-hand side variable, M-X or international trade deficit. One cause of international trade deficits is government budget deficit.

In many cases, we observe the two deficits rising at the same time. Thus, government budget deficit and international trade deficit are just like “Twins”. They are called “Twin Deficits”. ii)

“Trade deficit is an indicator of a good prospect of the economy ”

We can look at another cause of international trade deficit:

In the above equation of the equilibrium condition for national income, if G-T is held constant, an increase in M-X or international trade deficit goes hand-in-hand with an increase in the term I-S or investment in excess of savings.

Macroeconomics 27 Chapter I. Introduction

When investment exceeds savings, domestic savings falls short of the total investment. The difference comes from the foreign country. In other words, the difference between investment and savings is the foreign investment. If a country has a bad prospect, no foreigner would bring any investment to the country. The strong investment from foreign countries is an indicator of a good prospect of the economy.

At this time, we can reflect on the U.S. trade deficits. Many argue that the U.S. trade deficits are caused mainly by some countries’ unfair trade practices: The Japanese government might be blocking the imports of the U.S. goods. However, the above applications of the equilibrium condition for national income provide us with quite different perspectives: First, the U.S. trade deficit may be caused by the government budget deficit. In fact, it can be supported with historical data. Second, the U.S. trade deficit may be also caused by the strong investment demand, which goes beyond the savings by the American people and thus is supplemented by the foreigners bringing investment funds to the U.S. This is something to welcome.

2. Technical Part of the National Income Account (Review from the first year economics class)

1) How to measure the National Income and the Price Level?

(1) Nominal versus Real National Income

We have obtained the National Income by evaluating the aggregate output of the current period, say year t, at the current market prices. Let's call it the Nominal National Income (its notation is

Y t

):

Y t

=

P t

Q t

.........(1)

The nominal GDP was $190 billion in 1976 and $672 billion in 1989. Not all of what appears to be the growth of GDP is the indication of a raised standard of living. Why? Because part of the increase in the GDP is simply the result of an increase in the price level or inflation. Only the increase in the real quantity of goods and services or the aggregate output helps raise the standard of living. The change in the GDP consists of an increase in the price level and the growth of aggregate output.

How can we measure a change in the aggregate output alone, separately from the changes in the price level? We can do it by controlling the price level or by using the same price level for the two time points. First of all, we choose a certain time-point(year) for a benchmark, and call it the base period(year). There are two time points: the base period and the current period. In the base year the price level is P

0

, and the aggregate output Q

0

includes various final goods and services. In the current period the price level is P t

and the aggregate output Q t

.

The National Income of the base period is

Macroeconomics y

0

=

P

0

Q

0

28

........ (2)

Chapter I. Introduction

Note: There is no difference between the Nominal and Real National Income for the base period as P

0

= P t

for the base period.

The aggregate output of the current period Q t

evaluated at base period's prices give the Real

National Income (its notation is y t

): y t

=

P

0

Q t

....... (3)

The ratio of the real national income of the current period (3) to that of the base year (2) gives an indicator of the increase in the real national income. As the price level is being held constant here, the index measures how much the aggregate output has increased between the base and current year. It is called the Real National Income Index :

real income index =

P

0 Q t x 100

P

0

Q

0

=

P

0 h

Q

P

0 h

Q

0 h t h

+

+

P

P

0

0 s s

Q

Q

0 t s s

....

.....

x 100

(2) General Price Level

How can we measure a change in the price level itself? We have to control or fix the aggregate o utput this time. We can get the ratio of the current period's price level P t

to the base period's price

level P

0

. There are two different indexes depending on how to assign weights to individual price s. The first is to get the ratio of the price levels with fixed weights of the base period's output bas ket Q

0

. In this case, we also confine the outputs in this bundle to consumer goods. In Canada, th e basket includes about 490 items of consumer goods. This price index is called the Consumer P rice Index: consumer price index =

=

P t

Q

0 x 100

P

0

Q

0

P

P

0 h t h q

0 h

+

P q

0 h

+

P

0 t s s q

0 q

0 s s

....

.....

x 100

Alternatively, we can get the price index by getting the ratio of P t

to P

0

with fixed weights of the

Macroeconomics 29 Chapter II NIAS current period's aggregate output Q t

. The resultant price index is called the GDP Deflator:

GDP deflator =

P t

Q t x 100

P

0

Q t

=

P t

P

0 h h

Q t h

+

Q t h

+

P

P

0 s t s

Q t

Q t s s

....

.....

x 100

Note that the GDP deflator of the current period is equal to the ratio of the nominal to the real nat ional income: (1)/(3). Therefore, if the price level P represents the price index, then the Nominal

National Income is the Price Level times the Real National Income:

P = Y / y, or Y = P y.

(3) Numerical Examples

Refer to questions in Review Questions #1.

2) Various National Income Accounting System Equations (Review from Eco 100 or Eco 20).

GDP = GDI + IT = (W + I + R + P + D) + IT, where IT denotes indirect taxes; GDP denotes Gross Domestic Product; and GDI denotes

Gross Domestic Income.

NDP = GDP – D, where D denotes depreciation or capital consumption; and NDP denotes Net Domestic

Product.

NNI = NNP – IT,

Where NNI denotes Net National Income and NNP denotes Net National Product.

GDE = C + I + G + X-M

NDE = GDE - D

= C + Net I + G + X-M

GDI = GDP - IT

NDI = GDI - D

GNP = GDP - Net Investment Income Paid to Non-residents.

NNP = NDP - Net Investment Income Paid to Non-residents.

Macroeconomics 30 Chapter II NIAS

3) Issues and Problems of the Current National Income Accounting.

(1) Conceptual Problems:

Income may be considered to be the maximum that could be consumed in a given period consistent with the maintenance of wealth or of income potential. Alternatively and essentially equivalent it may be considered the sum of the amount that is consumed in a given period and that amount that is added to wealth. It is taken for granted that income has a direct bearing on material welfare, which may not be always true. For instance, the average income level of the Canadian native people fares well in national and international comparison. However, their longevity and level of satisfaction seem to be very low. There has a move to come up with a better and more comprehensive indicator of the well-being of people than the current National Income Account.

The new indicator should encompass income, longevity (health), and satisfaction.

(2) Missing Components of the National Income

We have already seen that the definition of GDP correctly excludes a) Intermediate goods: They are counted in the value of final goods which are made of intermediate goods. If the values of intermediate goods are included, in addition to the value of final goods, they are counted twice. b) Transfer income or Capital Gains: These items do not result from any productive services.

They do not represent any production. c) Capital Gains and Losses: Changes in the valuation of assets/wealth are clearly income at the personal level. However, they are usually not included in the National Income Account unless they represent new (current) production of goods or services. Sales of old houses, stocks, or antique may bring income to individuals, but do not increase any current production. They were included in the national income back at the time of new production. However, commission income of realtors is included in the current national income as the services rendered by them are new. The same is true of an antique dealer's value-added. Capital gains mostly arise from speculative activities. As speculation is usually a non-productive economic activity, gains from speculation are normally excluded from the calculation of national income.

(i) However, some capital gains do arise from what is a productive speculation. What is the productive speculation? Speculation that transferred goods from consumption at a time when they are plentiful and cheap to consumption at a time when they are scarce and expensive is productive.

An example is the speculation on seasonal products such as fish: Without speculation the price of fish would show a larger degree of seasonal fluctuations and much of fish would be wasted. In

Macroeconomics 31 Chapter II NIAS season, fish is so cheap that workers may not care too much about wastes in the processing procedure. Out of season, the price of fish is too high for some people to have enough of. As a speculator buys fish in season when fish is cheap, and releases it out of season when it is expensive, the price shows smaller seasonal fluctuations. The price of fish is now higher in season, so there will be less waste and more fish to be stored. This means a larger supply of fish than otherwise.

Out of season, fish price is lower, and there will be a larger demand for fish. This means more expenditure on fish. The speculator's capital gains represent a larger supply and demand or an increase in the national income.

(ii) Consumers-goods elements of job: Restaurant meals on an expense account are not included in the National Income. Expense account items of business representatives are goods and services which are clearly the consumption of goods and services on any reasonable interpretation, but they are classified as productive and therefore written off from the measured incomes of the person enjoying them. In Canada reform of tax regulations is under way to rectify this issue, which reduces the amount to be claimed in this way.

(iii) Household Production:

Over the past twenty years the rate of participation of women in the work force has risen at an average rate of 2.2 % per year from 37.1 % of the Canadian labour force in 1968 to 57.4 % in 1988.

The rapid rates of increases are also reflected in employment growth over the same period, a compound annual rate of growth for women of 3.9 % compared to 1.5 % for men. There are no markets or prices at which all of household production activities, such as laundry, home-cooking, baby-sitting, cleaning and etc. can be evaluated. So they are not taken into account of national income. As the women participate in the work force, they would now rely on the market for those goods which they used to produce at home. The formerly non-market activities, such as child-care and home-cooking give way to paid baby-sitters and meals in restaurants. They will pay for the baby sitter. The family may eat out more frequently instead of eating home-cooked meals. They may even pay for the cleaning ladies. These are counted as a net addition to output. Part of the growth in GDP simply reflects the substitution of market activities for non-market home production.

But growth will be more or less overstated depending on what happened to the non-market activity previously undertaking by these new entrants to labour force. If some of the previous non-market activity is forgone entirely, as a result of women entering the labour market, then measured GDP growth should be reduced by an equivalent amount. If, on the other hand, the housework is not foregone, and the women or other members of household somehow take up the slack, then measured GDP should not be adjusted.

The difficulty, of course, is to estimate the value of household work and the degree of substitutio n or replacement. In Canada, estimates have been prepared for 1971 and 1981 using data from Ce nsus Information and time use studies for a range of household activities. Valuing these activitie

Macroeconomics 32 Chapter II NIAS s at counterpart rates (prices: for instance, home-cooking is evaluated with the price of restaurant foods) in the market produced totals equivalent to 39.5 % of GDP in 1971 and 34.0% in 1981. (3

0% in 1990, unofficially) This unpaid work is estimated to account for 30 % of GDP in Canada.

The decline in the relative importance no doubt reflected other factors as well as the movement o f women into the market economy, but the overall effect was considerable.

Including the measured value of household work reduced the average rate of overall economic growth by 0.5 % per year. Alternatively put, Statistics Canada estimates that on average 0.5 percentage point of annual growth has come from the replacement of unpaid work with the market since 1971. In other words, even if the sum of home and market production does not increase at all, a mere substitution of market production for home production would make the GDP look as if it were growing at 5% per annum in Canada.

(iv) Underground Economy

Read the article entitled "Gross Deceptive Product" (GDP).

(3) False Components of the National Income

(i) Expenses of an Intermediate good nature

The current National Income Accounting System does not make any distinction between a leisurely driving and commutation for work. Expenses on commuting back and forth between home and work places are included in the national income. In fact they are costs for a further round of production, and should be excluded from the national income.

Macroeconomics 33 Chapter II NIAS

(ii) Systematic Exaggeration of the Government Role in a GDP Creation.

The following excellent example illustrates the seriousness of double-counting caused by the government: In the following two cases the real resources available for consumption, measured in the number of pairs of shoes, are identical, but the apparent National Income measured according to the present national income accounting system will be quite different.

Case 1. A ramp from a shoe factory to a highway is owned privately by a factory. Annually it costs a $1000 to maintain the ramp. The factory produces $100,000 worth of shoes. The costs and expenses of the ramp services are regarded as intermediate goods, and are already included in the values of the final goods or the shoes manufactured. Thus the ramp maintenance cost of $1000 is included in addition to the values of the shoes. The measure national income is $ 100,000

(= Y = C).

Case 2. Now government nationalizes the ramp and maintains it. The firm is required to pay annual tax of $1000 to government. Nothing has changed for the firm and the real economy: The firm is under the identical set of circumstances as in the original situation. The government makes expenditures in hiring workers and resources to upkeep the ramp. As the current National Income Accounting System values public goods provided by government on a cost basis, these government expenditures will be taken as increasing the national income. Now the measured income is the sum of private (shoes) and public goods (ramp services): Y = C + G = 100,000 + 1000 = 101,000. However, in fact, the cost of road services is already embodied in the value of the final goods or shoes. It is counted twice; once in the shoes and secondly in government expenditure (G).

How serious is this double counting in the public sector? For Canada, according to Reich (1986) intermediate goods account for 22.9 % of government expenditure or public goods. Therefore, the correct and true national income accounting identity, which includes various expenditures on final goods only, should be

Y = C + I + 0.77 G + X - M in Canada.

Macroeconomics 34 Chapter II NIAS

Appendix: How the Circular Flow Chart is obtained:

Some of you have noticed that I have jumped from the model with only consumers to the model with consumer, firms, government and foreign sector. This appendix is for the mind which requires some convincing as regards the transition from the simplest model with consumers only to the complex model with consumers, firms, government, and foreign sector.

1. Economy with Consumption Only.

We have already view the simplest economy with consumers only: AE = C only. If there is only

C on the aggregate expenditure side, the equilibrium condition for the national income is Y = C.

Example I: Let's suppose that the following table shows an annual production of all industries evaluated at the current market prices in a simplest economy. What is the current national income?

Industry Sales Revenues = Material Costs for Factor Costs (Value

Wheat

Flour

Bread

Deli-Bread

P x Q

$ 5

$ 8

$ 17

$ 25

Intermediate Goods

$ 0

$ 5

$ 8

$ 17

Added)

$ 5

$ 3

$ 9

$ 8

In the table, the sum of Value-Added of all industries is $ 5 + $3 + $9 + $8 = $25. Thus the current

National Income is $25.

2. Economy with Consumption and Investment: No government or Foreign Sectors

Macroeconomics 35 Chapter II Appendix

Now let’s add Firms’ demand for goods and services produced in the economy: Now AE will turn to C + I in the following example.

Example II:

Let's also add a machine-making industry, which produces final goods for investment.

Industry Sales Revenues = Material Costs for Factor Costs (Value

Wheat

Flour

Bread

Deli-Bread

Machine

P x Q

$ 5

$ 8

$ 17

$ 25

$ 50

Intermediate Goods

$ 0

$ 5

$ 8

$ 17

$ 0

Added)

$ 5

$ 3

$ 9

$ 8

$ 50

The supply side has Y = YS:

Y = VA's = $5 + 3 + 9 + 8 + 50 = $75

YS= P market x Q final

= 25 + 50= $75

We have so far assumed that households spend all their income: the entire Y is disposed of as

C. Let's now introduce savings: Households dispose of their income either in consumption spending or in savings. By the amount of the savings, which is a leakage from the circular flow, the national income does not go back to the flow of demand for goods: Y = C + S.

The demand is for deli-bread for consumption and for machines for investment: AE = C + I:

AE = C + I = 25 (Deli-Bread) + 50 (Machine) = $75

Note 1) Machines may be used in the production process. That does not make the machines an intermediate goods.

Intermediate goods are materials, which are to be embodied in their outputs. Machines may wear and tear, but will not be made into outputs. Machine are a capital good which endures many cycles of production.

The Circular Flow Chart for this economy is modified as follows:

Macroeconomics 36 Chapter II Appendix

Note: Savings of households may be channelled by financial intermediaries, such as banks, to firms as investment.

However, there is no guarantee that investment and savings are equal to each other as they are carried out by different economic agents: the first by households and the second by firms. For instance, when business outlook is break, households may cash their investment and hold their assets in deposits. Now savings become larger but investment smaller.

If they happen to be equal to each other, the circular flow will be maintained at the current level as the leakage(savings) is the same as the injection(investment). This is the equilibrium situation, meaning that the current state will persist in the absence of any disturbing forces.

Keynes noted that when savings exceeds investment, as leakage from the circular flow exceeds injection into it, the circular flow or the national income flow will diminish over time. He pointed out this problem as the cause of recession.

Example III: Inventory) The National Income should include all the factor payments(=VA) for goods produced of all the industries regardless of whether they are sold or unsold later in the economy. Income is created through the process of producing these aggregate outputs.

Macroeconomics 37 Chapter II Appendix

The existence of inventory compounds the output approach to the National Income. We should note that the value of inventories of final and intermediate goods should be included in the computation of the value of aggregate output. Sold intermediate goods get their value embodied in the value of final goods. The values of unsold intermediate goods are not reflected elsewhere and should be taken into account. Therefore, the Total Value of Output = Sold Final Goods + Unsold

Final Goods + Unsold Intermediate Goods:

YS = P x Q final sold + P x Q final unsold + P x Q intermediate unsold .

In the expenditure approach of getting the AE, the changes in inventories or Inventory

Accumulation of final and intermediate goods are regarded as Investment on inventories:

AE = C + I.

Numerical example: Refer to Assignment #1.

2) An Economy with Government

What complications does the introduction of government bring to the national income accounting system? i) The income approach national income Y (= W + R + I + P) should now include W, R, I, P paid by the government. They are all before-income-tax figures. The disposal of income should include direct taxes: Y = C + S + T. Consumers cannot spend taxes on final goods, and thus tax constitutes another leakage from the circular flow of the national income. ii) In the output approach, the value of goods and services produced by the government or public goods should be included in the National Product. There arises a question of how to come up with the market value of public goods? How to include the value of the Gibbon's park service on

Sunday? There is no market or market price for it. So the National Income Account calculates the value on a cost basis: The operating costs for the park service are its value. Therefore the value of public goods is equal to their production cost/expenditure.