Johnny Tremain - The West as U.S.

advertisement

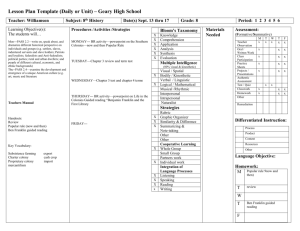

Sandy Fox TAH Project 2008 Johnny Tremain Unit Lesson Plan Objective: Understand the reasons/causes of the Revolutionary War through the use of fiction and non-fiction materials Time: 2-3 weeks Montana Social Studies Standards: Content Standard 1—Students access, synthesize, and evaluate information to communicate and apply social studies knowledge to real world situations. Benchmarks (end of 8th grade) 1. Apply the steps of an inquiry process (i.e., identify question or problem, locate and evaluate potential resources, gather and synthesize information, create a new product, and evaluate product and process). 2. Assess the quality of information (e.g., primary or secondary sources, point of view and embedded values of the author). Content Standard 2—Students analyze how people create and change structures of power, authority, and governance to understand the operation of government and to demonstrate civic responsibility. rights, within agreements). Benchmarks (end of 8th grade) 5. Identify and explain the basic principles of democracy (e.g., Bill of Rights, individual common good, equal opportunity, equal protection of the laws, majority rule). 6. Explain conditions, actions and motivations that contribute to conflict and cooperation and among groups and nations (e.g., discrimination, peer interaction, trade Content Standard 3--Students apply geographic knowledge and skills (e.g., location, place, human/environment interactions, movement, and regions). products, Benchmarks (end of 8th grade) 4. explain how movement patterns throughout the world (e.g., people, ideas, diseases, food) lead to interdependence and/or conflict. Content Standard 4—Students demonstrate an understanding of the effects of time, continuity, and change on historical and future perspectives and relationships. eyewitnesses, sources used. and Benchmarks (end of 8th grade) 1. interpret the past using a variety of sources (e.g., biographies, documents, diaries, interviews, internet, primary source material) and evaluate the credibility of 2. describe how history can be organized and analyzed using various criteria to group people events (e.g., chronology, geography, cause and effect, change, conflict, issues). 3. use historical facts and concepts and apply methods of inquiry (e.g., primary documents, interviews, comparative accounts, research) to make informed decisions as responsible citizens. equality, United States, and world 4. identify significant events and people and important democratic values (e.g., freedom, privacy) in the major eras/civilizations of Montana, American Indian, history. Habits of the Mind: Understand the significance of the past to their own lives, both private and public, and to their society. Perceive past events and issues as they were experienced by people at the time, to develop historical empathy as opposed to present-mindedness. Understand how things happen and how things change how human intentions matter, but also how their consequences are shaped by the means of carrying them out, in a tangle of purpose and process. Grasp the complexity of historical causation, respect particularity, and avoid excessively abstract generalizations. Recognize the importance of individuals who have made a difference in history, and the significance of personal character for both good and ill. Read widely and critically in order to recognize the difference between fact and conjecture, between fact and conjecture, between evidence and assertion, and thereby to frame useful questions. Background Johnny Tremain takes place during the summer of 1773, ten years after the French and Indian War and after the Boston Massacre. The British governed the American colonies and few people had any complaints about their rule. There was little interest in politics during this time also. Johnny Tremain teaches the reader about common every day life in eighteenth-century America—mainly Boston. Most of the characters in the novel are fictional with a few real-life historical figures such as John Hancock, Paul Revere and Josiah Quincy. Also mentioned are some other earlier patriots such as John Adams, Dr. Joseph Warren and James Otis. Vocabulary Apprentices, penetrate, infernally, flaccid, parasitic, autocratic, annealing, formidable, Ethereal, apoplectic, pious, genteel, graven image, agape, divot, reverie, repousse’, Protuberant eyes, lamentable, gadroon, skulking, prosperous, beaux, dire, eloquence, Crucible, insufferable, slavishly, poultice, erstwhile, proclamations, indolent, belligerent Artifacts (slides, pictures) Silversmith items/tools (pictures located on the Internet or Picturing America photos) Photos of historical people such as Paul Revere, John Hancock, Sam Adams, John Adams, George Washington, and events such as Battles of Lexington and Concord, Boston Massacre and the Boston Tea Party Strategies: 1. As students read Johnny Tremain they will make a three column chart. The first column will be Historical fact, Fiction, Not sure. As we read the book together, students will fill out their own chart. The third column will be shared with the class and a whole group list will be kept and analyzed at the end of the book. After reading the book, students will break into small groups and research questions using non-fiction books and the Internet. Students will access these websites as part of this activity. http://history.howstuffworks.com/revolutionary-war and http://www.nevada.edu/~treed/trwebquest. Several non-fiction books will be available. See attached bibliography. Student groups will use the Internet and at least two nonfiction books to complete this task. 2. Primary Sources Discuss primary and secondary sources in small groups and then come together in whole group discussion. Students will analyze Paul Revere’s famous engraving of the Boston Massacre and look up newspaper accounts of event. Discuss what happened and how it compared with the engraving. Students will analyze the Longfellow’s poem Midnight Ride of Paul Revere. Use attached documents for assessment: Discuss the importance of analyzing primary documents, perspective, and images created years later that may distort reality. Use this website as a resource http://www.sdcoe.k12.ca.us/SCORE/Tremain/tremaintg.html Paul Revere's Ride LISTEN, my children, and you shall hear Of the midnight ride of Paul Revere, On the eighteenth of April, in Seventy-Five; Hardly a man is now alive Who remembers that famous day and year. He said to his friend, "If the British march By land or sea from the town to-night, Hang a lantern aloft in the belfry arch Of the North Church tower, as a signal light, -One, if by land, and two, if by sea; And I on the opposite shore will be, Ready to ride and spread the alarm Through every Middlesex village and farm, For the country-folk to be up and to arm." Then he said "Good-night!" and with muffled oar Silently rowed to the Charlestown shore, Just as the moon rose over the bay, Where swinging wide at her moorings lay The Somerset, British man-of-war; A phantom ship, with each mast and spar Across the moon like a prison-bar, And a huge black hulk, that was magnified By its own reflection in the tide. Meanwhile, his friend, through alley and street Wanders and watches with eager ears, Till in the silence around him he hears The muster of men at the barrack door, The sound of arms, and the tramp of feet, And the measured tread of the grenadiers, Marching down to their boats on the shore. Then he climbed the tower of the Old North Church, By the wooden stairs, with stealthy tread, To the belfry-chamber overhead, And startled the pigeons from their perch On the somber rafters, that round him made Masses and moving shapes of shade, -By the trembling ladder, steep and tall, To the highest window in the wall, Where he paused to listen and look down A moment on the roofs of the town, And the moonlight flowing over all. Beneath, in the churchyard, lay the dead, In their night-encampment on the hill, Wrapped in silence so deep and still That he could hear, like a sentinel's tread, The watchful night-wind, as it went Creeping along from tent to tent, And seeming to whisper, "All is well!" A moment only he feels the spell Of the place and the hour, the secret dread Of the lonely belfry and the dead; For suddenly all his thoughts are bent On a shadowy something far away, Where the river widens to meet the bay, -A line of black, that bends and floats On the rising tide, like a bridge of boats. Meanwhile, impatient to mount and ride, Booted and spurred, with a heavy stride On the opposite shore walked Paul Revere. Now he patted his horse's side, Now gazed on the landscape far and near, Then, impetuous, stamped the earth, And turned and tightened his saddle-girth; But mostly he watched with eager search The belfry-tower of the Old North Church, As it rose above the graves on the hill, Lonely and spectral and somber and still. And lo! as he looks, on the belfry's height A glimmer, and then a gleam of light! He springs to the saddle, the bridle he turns, But lingers and gazes, till full on his sight A second lamp in the belfry burns! A hurry of hoofs in a village street, A shape in the moonlight, a bulk in the dark, And beneath, from the pebbles, in passing, a spark Struck out by a steed flying fearless and fleet: That was all! And yet, through the gloom and the light, The fate of a nation was riding that night; And the spark struck out by that steed, in his flight, Kindled the land into flame with its heat. He has left the village and mounted the steep, And beneath him, tranquil and broad and deep, Is the Mystic, meeting the ocean tides; And under the alders that skirt its edge, Now soft on the sand, now loud on the ledge, Is heard the tramp of his steed as he rides. It was twelve by the village clock, When he crossed the bridge into Medford town. He heard the crowing of the cock, And the barking of the farmer's dog, And felt the damp of the river fog, That rises after the sun goes down. It was one by the village clock, When he galloped into Lexington. He saw the gilded weathercock Swim in the moonlight as he passed, And the meeting-house windows, blank and bare, Gaze at him with a spectral glare, As if they already stood aghast At the bloody work they would look upon. It was two by the village clock, When he came to the bridge in Concord town. He heard the bleating of the flock, And the twitter of birds among the trees, And felt the breath of the morning breeze Blowing over the meadows brown. And one was safe and asleep in his bed Who at the bridge would be first to fall, Who that day would be lying dead, Pierced by a British musket-ball. You know the rest. In the books you have read, How the British regulars fired and fled, -How the farmers gave them ball for ball, From behind each fence and farm-yard wall, Chasing the red-coats down the lane, Then crossing the fields to emerge again Under the trees at the turn of the road, And only pausing to fire and load. So through the night rode Paul Revere; And so through the night went his cry of alarm To every Middlesex village and farm, -A cry of defiance and not of fear, A voice in the darkness, a knock at the door, And a word that shall echo forevermore! For, borne on the night-wind of the Past, Through all our history, to the last, In the hour of darkness and peril and need, The people will waken and listen to hear The hurrying hoof-beat of that steed, And the midnight-message of Paul Revere. Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, 1860 3. Create a timeline lesson for major players in the Revolutionary War using JoAnne Fox’s lesson plan. Divide students into pairs. There should be two groups for each famous person. Provide them with facts about one of the famous people found below. Teachers will take several facts from the biographical sketches placed in such a way so that students can cut them apart. They should not be in chronological order. Students will choose what they believe are the three most important facts about their person and then paste their facts on the timeline that is created with colored tape that is placed on a long wall. Each famous person is represented by a different color. Students will then have another sheet of facts and place them in order on butcher paper noting the three most important facts. Butcher paper is then placed on a wall or held by students as they justify why they believe they have selected the three most significant events in this person life. Assessment: Rubric on participation/cooperation/understanding concepts Materials needed: Each pair/group should have a pair of scissors, fact sheet, butcher paper, colored painters tape, and markers Paul Revere Revere, Paul (1735-1818), an American patriot, silversmith, and engraver. His fame as a hero of the American Revolution is largely due to Henry Wadsworth Longfellow's popular, though somewhat inaccurate, poem Paul Revere's Ride. Revere was also a cartoonist and a pioneer industrialist. Patriot Leader Revere was born in Boston. His father, of French Huguenot descent, changed his name from de Revoir to Revere. He taught his silversmith craft to Paul, who became a master of the trade. At the age of 21, Paul Revere joined the British in an unsuccessful attack on the French fort at Crown Point, New York. He returned to Boston, where he continued his silversmith work and also branched out into other crafts, including copper engraving. As difficulties mounted between the American colonies and England, Revere engraved political cartoons in favor of the colonies. His cartoons, although sometimes crude and exaggerated, were effective propaganda. He also made pictorial engravings. In 1773 Revere led several associates in the Boston Tea Party raid. The next year he rode to Philadelphia, rushing the Suffolk Resolves to the first Continental Congress. They were adopted, including a resolution to create colonial militia. Revere became official courier for Massachusetts. On April 16, 1775, he spurred to Concord to warn colonists that the British aimed to seize military supplies. This ride was at least as important as his midnight ride two days later. The Midnight Ride While in Concord, Revere and militiamen arranged the signals for his ride to Lexington. According to his report, "If the British went by water, we would show two lanthorns [lanterns] in the North Church steeple; and, if by land, one." Almost a century later (1863) the ride was commemorated by Longfellow in the poem that begins: Listen, my children, and you shall hear Of the midnight ride of Paul Revere, On the eighteenth of April, in SeventyFive; Hardly a man is now alive Who remembers that famous day and year. On the night of April 18, Revere left Charlestown to alert the countryside that the British were coming. After warning John Hancock and Samuel Adams to flee Lexington, he was joined by William Dawes, who had made a similar ride from Boston. They rushed toward Concord, meeting along the way a young doctor, Samuel Prescott, who asked to join them. They were approached by British troops and Revere was captured. Dawes fled to Lexington, but Prescott rode on to Concord. Revere was soon released and returned on foot to Lexington, where he helped Hancock and Adams get away. Later Years Although he wanted to serve in the Continental Army, Revere was assigned to civilian work. He designed and printed the official colonial seal and the Massachusetts state seal. Revere also directed the manufacturing of gunpowder. After the war, Revere returned to silver-smithing, making pieces that are now collectors' items. He also cast bells and made cannon. His foundry manufactured bolts and copper fittings for the Constitution ("Old Ironsides"). Revere invented a process for rolling sheet copper, used in steam boilers. To the end of his long life he wore the garb of the Revolutionary era. John Adams Learned and thoughtful, John Adams was more remarkable as a political philosopher than as a politician. "People and nations are forged in the fires of adversity," he said, doubtless thinking of his own as well as the American experience. Adams was born in the Massachusetts Bay Colony in 1735. A Harvard-educated lawyer, he early became identified with the patriot cause; a delegate to the First and Second Continental Congresses, he led in the movement for independence. During the Revolutionary War he served in France and Holland in diplomatic roles, and helped negotiate the treaty of peace. From 1785 to 1788 he was minister to the Court of St. James's, returning to be elected Vice President under George Washington. Adams' two terms as Vice President were frustrating experiences for a man of his vigor, intellect, and vanity. He complained to his wife Abigail, "My country has in its wisdom contrived for me the most insignificant office that ever the invention of man contrived or his imagination conceived." When Adams became President, the war between the French and British was causing great difficulties for the United States on the high seas and intense partisanship among contending factions within the Nation. His administration focused on France, where the Directory, the ruling group, had refused to receive the American envoy and had suspended commercial relations. Adams sent three commissioners to France, but in the spring of 1798 word arrived that the French Foreign Minister Talleyrand and the Directory had refused to negotiate with them unless they would first pay a substantial bribe. Adams reported the insult to Congress, and the Senate printed the correspondence, in which the Frenchmen were referred to only as "X, Y, and Z." The Nation broke out into what Jefferson called "the X. Y. Z. fever," increased in intensity by Adams's exhortations. The populace cheered itself hoarse wherever the President appeared. Never had the Federalists been so popular. Congress appropriated money to complete three new frigates and to build additional ships, and authorized the raising of a provisional army. It also passed the Alien and Sedition Acts, intended to frighten foreign agents out of the country and to stifle the attacks of Republican editors. President Adams did not call for a declaration of war, but hostilities began at sea. At first, American shipping was almost defenseless against French privateers, but by 1800 armed merchantmen and U.S. warships were clearing the sea-lanes. Despite several brilliant naval victories, war fever subsided. Word came to Adams that France also had no stomach for war and would receive an envoy with respect. Long negotiations ended the quasi war. Sending a peace mission to France brought the full fury of the Hamiltonians against Adams. In the campaign of 1800 the Republicans were united and effective, the Federalists badly divided. Nevertheless, Adams polled only a few less electoral votes than Jefferson, who became President. On November 1, 1800, just before the election, Adams arrived in the new Capital City to take up his residence in the White House. On his second evening in its damp, unfinished rooms, he wrote his wife, "Before I end my letter, I pray Heaven to bestow the best of Blessings on this House and all that shall hereafter inhabit it. May none but honest and wise Men ever rule under this roof." Adams retired to his farm in Quincy. Here he penned his elaborate letters to Thomas Jefferson. Here on July 4, 1826, he whispered his last words: "Thomas Jefferson survives." But Jefferson had died at Monticello a few hours earlier. Sam Adams (1722–1803) was an American Revolutionary leader. He was a second cousin of John Adams, second President of the United States. A skilled politician and propagandist, Sam Adams (as he was popularly called), more than any other man, prepared the way for the American Revolution. During the Revolutionary period, he stirred the colonists against Great Britain through writings, speeches, and personal contact. To his opponents, Adams was the “Chief Incendiary,” exploiting colonial differences with Britain to advance his own radical ideas. To his supporters, he was the “Firebrand of Independence,” dedicated to the cause of American liberty. Early Career. Sam Adams was born in Boston. He graduated from Harvard in 1740 and received a master's degree in 1743. He studied law for a while, then entered business. He was unsuccessful in a number of ventures, and in 1756 became tax collector of Boston. Adams left this post in 1764, after falling behind in collections. He then turned his attention to politics, devoting his energies to the struggle with Great Britain over colonial rights. Revolutionary Period. By 1764 Sam Adams was already a leading figure in Boston politics, having opposed for some years the small group of aristocratic families that virtually ruled Massachusetts. He took a prominent part in the agitation against the Sugar Act of 1764 and the Stamp Act of 1765, protesting “taxation without representation.” In 1765 he helped form the Sons of Liberty, a secret revolutionary society. Serving in the Massachusetts legislature, 1765–74, Adams became leader of the radicals and was clerk of the House, 1766–74. Adams stirred up opposition to the Townshend Acts (1767), and was an organizer of the Non-Importation Association in 1768. During a period of relative calm, 1770–72, Sam Adams kept discontent alive by writing inflammatory newspaper articles. In 1772 he organized the first Committee of Correspondence. He drafted the Boston Declaration of Rights in 1772 and was influential in the agitation that led to the Boston Tea Party. After passage of the Intolerable Acts, 1774, Adams was one of the first to call for a congress of the colonies. He was chosen as a delegate to the First and Second Continental Congresses, 1774–75. He signed the Declaration of Independence in 1776. After Independence. As Adams was more a revolutionary agitator than statesman, his influence declined after American independence was declared. He was a member of the Continental Congress until 1781, serving on the committee that drafted the Articles of Confederation. Although at first opposed to a strong central government, Adams voted for ratification of the Federal Constitution at the Massachusetts Convention of 1788. He was lieutenant governor of Massachusetts, 1789–93, and governor, 1794–97 Benjamin Franklin Franklin, Benjamin (1706–1790), an American statesman, scientist, and author. He was one of the great figures in the colonial and Revolutionary periods of American history. Franklin was a distinguished scientist and a prominent writer. He served as a diplomatic representative of the American colonies to Great Britain and, later, of the United States to France. He gained support in Europe for the American fight for independence from Britain, and was instrumental in obtaining the assistance of France for the United States during the Revolutionary War. Franklin is the only person whose name appears on all four of the important documents associated with the founding of the United States: the Declaration of Independence, the treaty of alliance with France, the Treaty of Paris (the treaty that ended the war with Great Britain), and the Constitution. Franklin first gained international fame through his scientific achievements. He was a pioneer in the study of electricity, proving that lightning is an electrical phenomenon. He was granted honorary degrees by Harvard, Yale, Oxford, and other institutions, and was a member of several learned societies. Franklin was also America's first famous writer. His weekly newspaper, the Pennsylvania Gazette, was widely read throughout the colonies. He also published Poor Richard's Almanack, a pamphlet that appeared each year from 1732 to 1757. It contained weather information, a piece of humorous writing by Franklin, and many everyday proverbs and jokes that he collected and rewrote to fit American life. Some articles from it were published in Europe. Franklin's only book was his Autobiography, published in part in 1791 and in complete form in 1868. The book covers the first 50 years of his life. Few people have been as diverse as Franklin in their interests or as varied in their accomplishments. He symbolized the American character to the world and was the most eminent American of his time. Early Years Benjamin Franklin was born in Boston on January 17, 1706, the 15th of 17 children. His father, Josiah, was a soapmaker and candlemaker who taught his son to read and sent him to school for two years. After working for a time in his father's shop, Franklin was apprenticed at the age of 12 to his brother James, a printer. Franklin quickly became skilled in the printing trade. He also took an early interest in writing, and by 1722 was composing humorous pieces which were published under a pen name in James Franklin's newspaper, the New England Courant. When James was imprisoned briefly in 1722 for his criticism of Massachusetts public officials, Franklin took over as publisher of the Courant. In 1723 the brothers began to quarrel, however, and Benjamin left Boston for Philadelphia. He found work there in a print-shop. Although only 17, Franklin gained a reputation as a skilled printer. The governor of Pennsylvania offered to help him start a shop of his own, and sent him to England to purchase equipment. The governor, however, failed to send the money to buy the equipment, and Franklin, his funds exhausted, was stranded in London. He found work there as a printer and stayed for a year and a half before returning to Philadelphia in 1726. In 1728 Franklin and a friend started their own printing business. In two years Franklin became sole owner of the shop and publisher of the Pennsylvania Gazette. A debating club, the Junto, started by Franklin in 1727, was the forerunner of the American Philosophical Society (founded 1743). Franklin and Deborah Read (1708–1774) entered into a common-law marriage in 1730. They had two children—a son who died in infancy, and a daughter, Sarah (1744–1808). Franklin also had an illegitimate son, William (1731– 1813), who grew up in his household and served as his assistant on some of his diplomatic missions. William became royal governor of New Jersey in 1763 and remained loyal to the crown in the American Revolution. Business and Scientific Successes Franklin's printing business was a financial success. The popularity of the Pennsylvania Gazette made him well known in Philadelphia and throughout the colonies. Even more popular, however, was Poor Richard's Almanack (so called from the pen name, Richard Saunders, under which it appeared). It sold about 10,000 copies per year. Franklin received so much work that he started printshops in several other cities. By 1748, at the age of 42, he had made enough money to retire. Franklin hoped to spend the rest of his life studying philosophy and investigating the natural sciences. He began to conduct various scientific experiments. Franklin had been interested in the study of electricity since about 1746. He advanced the concept that electricity flows between two objects when one has a positive electrical charge and the other a negative electrical charge. Franklin suspected that lightning is electrical, and proved this in his kite experiment in 1752. (For a description of this experiment ) The kite experiment led Franklin to invent the lightning rod to protect buildings from damage from lightning. Because of his achievements in the field of electricity, he was elected a fellow of the Royal Society, a scientific society in England, in 1756. Franklin also compiled weather data, studied the seas, and worked on various inventions. He printed the first chart of the Gulf Stream in the Atlantic Ocean and investigated the effects of the Gulf Stream on sea travel. He devised the Franklin stove, a heating stove that operates on the same principle as a hot-air furnace. When his eyesight became poor, he invented bifocal eyeglasses for himself (1780). Public Service Franklin became involved in a number of civic projects in Philadelphia. He was active in starting a city hospital in 1751 and in establishing the Academy of Philadelphia, which later became the University of Pennsylvania. He worked to get the streets paved and street lighting improved, and helped to organize the first police force and fire company in the colonies. He was Philadelphia's postmaster, 1737–53. Franklin served Pennsylvania as clerk of its assembly, 1736–51, and as a member of the assembly, 1751–64. He represented Pennsylvania at a meeting of the colonies at Albany, New York, in 1754. In the French and Indian War (1754–60) Franklin organized militia companies and bought military supplies at his own expense. He was deputy postmaster general for the colonies, 1753–74. The Pennsylvania colony had been organized by William Penn. His descendants, who lived in England, thought they should not have to pay taxes on their lands. The colony needed the tax money, however, and in 1757 Franklin was sent to England to put the matter before the government. He remained for five years, and succeeded in having the Penn estates declared taxable. Soon there were new disputes with the Penn heirs, and in 1764 Franklin was again sent to England to discuss a new form of government for Pennsylvania. New problems concerning all the American colonies changed the nature of his mission. The Stamp Act was passed by the Parliament in 1765 as a means of taxing the colonies. Franklin did not regard the act as illegal, but in an appearance before the House of Commons he explained with great clarity why it was undesirable. His arguments were widely read, and were a central factor in the decision to repeal the Stamp Act in 1766. Franklin was asked to remain in England as agent for Pennsylvania. In America, resentment against British rule was becoming more intense. Franklin worked steadily to improve relations between Britain and the American colonies, but they grew worse year by year. At last he saw that his efforts were hopeless. He returned to America in May, 1775. In the Cause of American Independence Franklin at once became a member of the Continental Congress, where he was given the task of organizing a postal system and was made postmaster general. He also served as a member of the committee that prepared the Declaration of Independence. The United States badly needed assistance in fighting the war. A three-man commission, including Franklin, was sent to France in 1776 to try to arrange a treaty. The French government had not recognized the United States, but Franklin was received unofficially with great enthusiasm. His renown and his diplomatic skills were of the greatest benefit in gaining the treaty of alliance, signed in 1778. Shortly afterward, Franklin was appointed sole American agent to France. His main duty the next few years was to raise money for continuing the war. In 1781 Franklin, John Adams, and John Jay were named to a commission to negotiate peace with Great Britain. Their efforts ended in the Treaty of Paris, signed in 1783. In 1785, Franklin turned over his responsibilities to Thomas Jefferson and returned home. Back in Philadelphia, Franklin was chosen president of the Supreme Executive Council of Pennsylvania. He served in this office for three years. In 1787 he became a delegate to the Constitutional Convention. Franklin preached compromise to the other delegates, and when the Constitution was finished, he urged that it be unanimously adopted. His last public act was to sign a petition to Congress for the immediate abolition of slavery. He died April 17, 1790. James Otis James Otis was one of the most passionate and effective protectors of American rights during the 1760s, but his bright star dimmed during his lifetime and remains so today. He was born in West Barnstable on Cape Cod, the son of a prominent Massachusetts political figure with the same name. Young Otis graduated from Harvard College in 1743, practiced law briefly in Plymouth, and in 1750, settled in Boston, where he became a highly respected lawyer. At the beginning of his career, Otis was a political conservative and was rewarded for his loyalty in 1756, with an appointment as an advocate general in the vice admiralty court. Among his duties was the responsibility to prosecute smugglers. Many New England merchants had resorted to illegal activities in order to avoid the onerous Acts of Trade that governed commerce throughout the British Empire; the Crown attempted to crack down on the violators and had introduced a new legal instrument — the writs of assistance — to aid in the process. Those writs were general search warrants that enabled customs officials to enter business and homes in the hope of finding vaguely defined contraband. Many colonists, including Otis, were deeply concerned about what they regarded as an unconstitutional practice. Otis's conversion from a conservative royal employee to radical critic is not explained solely in terms of constitutional scruples. In 1761, the newly appointed governor of Massachusetts, Sir Francis Bernard, had selected Thomas Hutchinson to be the new Chief Justice of the colony’s Superior Court; the candidacy of James Otis Sr. was bypassed. Fueled both by principle and a desire for revenge, Otis resigned his position in 1761, and accepted a call from Boston merchants to represent them in a fight to prevent the renewal of authority for the writs of assistance. The case was heard in February and Otis, in the fashion of the day, delivered an eloquent fivehour argument in which he maintained that the writs were a violation of the colonists’ natural rights and that any act of Parliament that abrogated those rights was null and void. He stated in part: A man’s house is his castle; and whilst he is quiet, he is as well guarded as a prince in his castle. This writ, if it should be declared legal, would totally annihilate this privilege. Custom-house officers may enter our houses when they please; we are commanded to permit their entry. Their menial servants may enter, may break locks, bars, and everything in their way; and whether they break through malice or revenge, no man, no court may inquire. In attendance at court that day was a young attorney, John Adams, who would later cite this moment as the first scene in the first act of resistance to oppressive British policies. Otis lost the case; the writs of assistance were renewed. However, the matter had been brought to popular attention and few officials in the future were willing to incur public wrath by employing the orders. Otis became an instant celebrity and a month later was elected to a seat in the General Court (legislature). As time passed and the list of American grievances against the Crown grew, Otis played an ever more prominent role in advancing the colonists' interests. In 1764, he headed the Massachusetts committee of correspondence. He also spoke and wrote widely, and won special praise for The Rights of the British Colonies Asserted and Proved (1764), in which he made the case against Parliamentary taxation of the colonies. The following year he was a leading figure at the Stamp Act Congress in New York City. Otis’s open advocacy of American rights grated on many officials' nerves; his election to the speakership of the General Court in 1766, was voided by the governor’s veto. Undeterred, Otis teamed with Samuel Adams to confront the next crisis: enforcement of the Townshend Duties in 1767. The firebrand duo drafted a circular letter to enlist the other colonies in planned resistance to the new taxes. In 1769, at the height of his popularity and influence, Otis was pulled from the public stage. He had infuriated a Boston custom-house official with a vicious newspaper attack; the official beat Otis on his head with a cane. For the remainder of his life, Otis was subject to long bouts of mental instability. He was unable to participate in public affairs and spent most of his time wandering through the streets of Boston, enduring the taunts of a populace that had quickly forgotten his contributions. Otis was struck and killed by lightning in May 1783. James Otis on The Writs of Assistance February, 1761 ... Project• American Historical Assoc. Shop• Books• Send E-Cards• Posters James Otis on The Writs of Assistance February, 1761May it please your Honours: I was desired by one of the court to look into the (law) books, and consider the James Otis on The Writs of Assistance February, 1761May it please your Honours: I was desired by one of the court to look into the (law) books, and consider the question http://www.history1700s.com/page1795.shtml American Revolution - In Opposition to Writs of Assistance by James Otis (1725-1783) February, 1761 James Otis was Advocate-General when the legality of these warrents was attacked, but promptly resigned his office when called upon to defend that legality. The Boston merchants then retained him as their counsel to oppose the writs before James Otis was Advocate-General when the legality of these warrents was attacked, but promptly resigned his office when called upon to defend that legality. The Boston merchants then retained him as their counsel to oppose the writs before the ... http://www.americanrevolution.com/InOppositiontoWritsofAssistance.htm James Otis on the Stamp Act An Oration Delivered Before the Governor and Council In Boston, December 20, 1765 ... Project• American Historical Assoc.Shop• Books• Send E-Cards• Posters James Otis on the Stamp Act An Oration Delivered Before the Governor and Council In Boston, December 20, 1765.It is with great grief that I appear before your James Otis on the Stamp Act An Oration Delivered Before the Governor and Council In Boston, December 20, 1765.It is with great grief that I appear before your Excellency ... http://www.history1700s.com/page1794.shtml James Otis Born: 5-Feb-1725 Birthplace: West Barnstable, MA Died: 23-May-1783 Location of death: Andover, MA Cause of death: Accident - Misc Gender: Male Race or Ethnicity: White Sexual orientation: Straight Occupation: Government Nationality: United States Executive summary: Massachusetts patriot and pamphleteer Father: James Otis (b. 1702, d. 1778) Sister: Mercy Otis Warren (historian) University: Harvard University (1743) Treason Struck by Lightning causing his death (23-May-1783) Author of books: Rudiments of Latin Prosody (1760, nonfiction) A Vindication of the Conduct of the House of Representatives of the Province of Massachusetts Bay (1762, pamphlet) The Rights of the British Colonies Asserted and Proved (1764, pamphlet) A Vindication of the British Colonies against the Aspersions of the Halifax Gentleman in his Letter to a Rhode Joseph Warren Revolutionary War Major General WARREN, Joseph, physician, born in Roxbury, Mass., 11 June, 1741; died in Charlestown, Mass., 17 June, 1775. he was descended from Peter Warren, whose name appears on the town records of Boston in 1659, where he is called "mariner." Peter's second son, Joseph, built a house in 1720 in what is now Warren street, Roxbury, and died there in 1729. His son, Joseph, born in 1696, married, 29 Nay, 1740, Mary, daughter of Dr. Samuel Stevens, of Roxbury, and the subject of this sketch was their eldest child. Joseph Warren, the father, was a thrifty farmer, much respected by his townsmen, by whom he was elected to several offices of trust; He was interested in fruitraising, and introduced into that part of the country the apple long known as the "Warren russet." In October, 1755, while gathering fruit in his orchard, he fell from the ladder and was instantly killed. His son, Joseph, was graduated at Harvard in 1759, and in the following year was appointed master of the Roxbury grammar-school. He studied medicine with Dr. James Lloyd, and began to practice his profession in 1764. He married, 6 Sept., 1764, Miss Elizabeth Hooton, a young lady who had inherited an ample fortune. The passage of the stamp-act in the following year led Dr. Warren to publish several able articles in the Boston "Gazette." About this time began his intimate friendship with Samuel Adams, who conceived a warm admiration for him, and soon came to regard him as a stanch and clear-headed ally, who could be depended upon under all circumstances. On the occasion of the Townshend acts, Dr. Warren's articles, published under the signature of "A True Patriot," aroused the anger of Gov. Francis Bernard, who brought the matter before his council, and endeavored to prosecute Messrs. Edes and Gill. The publishers of the "Gazette," for giving currency to seditious libels ; but the grand jury refused to find a bill against these gentlemen. The affair created much excitement in Boston, and led Gov. Bernard to write to Lord Hillsborough, secretary of state for the colonies, recommending the arrest of the publishers on a charge of treason. In the affair of the sloop "Liberty," in June, 1768, Dr. Warren was one of the committee appointed to wait upon the governor at his country-seat at Jamaica Plain, and protest against the impressments of seamen and the vexatious enforcement of the revenue laws. He was present at every town-meeting held in Boston, from the arrival of the British troops in October, 1768, to their removal in March, 1770, and he was one of the committee of safety appointed after the so-called "massacre" on 5 March. In July he was appointed on a committee to consider the condition of the town, and send a report to England. It was apparently of him that a Tory pamphleteer wrote: “One of our most bawling demagogues and voluminous writers is a crazy doctor." In March, 1772, he delivered the anniversary oration upon the "massacre"; in November his name was recorded immediately after those of James Otis and Samuel Adams in the list of the first committee of correspondence. During the next two years he was m active co-operation with Samuel Adams, and when, in August, 1774, that leader went to attend the meeting of the Continental congress at Philadelphia, the leadership of the party in Boston devolved upon Dr. Warren. On 9 Sept., 1774, the towns of Suffolk County met in convention at Milton, and Dr. Warren read a paper drawn up by himself, and since known as the "Suffolk resolves." The resolutions, which were adopted unanimously, declared that a king who violates the chartered rights of his people forfeits their allegiance; they declared the regulating act null and void, and ordered all the officers appointed under it to resign their offices at once; they directed the collectors of taxes to refuse to pay over money to Gen. Gate's treasurer; they advised the towns to choose their own militia officers; and they threatened Gage that, should he venture to arrest anybody for political reasons, they would retaliate by seizing upon the crown officers as hostages. A copy of these resolutions, which virtually placed Massachusetts in an attitude of rebellion, was forwarded to the Continental congress, which forthwith approved them and pledged the faith of all the other colonies that they would aid Massachusetts in case armed resistance should become inevitable. After the meeting of the Provincial congress at Concord in October, Dr. Warren acted as chairman of the committee of safety, charged with the duty of organizing the militia and collecting military stores. As the 5th of March, 1775, drew near, several British officers were heard to declare that any one who should dare to address the people in the Old South church on this occasion would surely lose his life. As soon as he heard of these threats, Dr. Warren solicited for himself the dangerous honor, and at the usual hour delivered a stirring oration upon “the baleful influence of standing armies in time of peace." The concourse in the church was so great that, when the orator arrived, every approach to the pulpit was "blocked up" and rather than elbow his way through the crowd, which might lead to some disturbance, he procured a ladder and climbed in through a large window at the back of the pulpit. About forty British officers were present, some of whom sat on the pulpit-steps, and sought to annoy the speaker with groans and hisses, but everything passed off quietly. On Tuesday evening, 18 April, observing the movements of the British troops, Dr. Warren dispatched William Dawes, by way of Roxbury, and Paul Revere, by way of Charlestown, to give the alarm to the people dwelling on the roads toward Concord. Next morning, on hearing the news of the firing at Lexington, he left his patients in charge of his pupil and assistant, William Eustis, and rode off to the scene of action. He seems to have attended a meeting of the committee of safety that morning at the Black Horse tavern in Menotomy (now Arlington), and there to have consulted with Gen. William Heath. By the time Lord Percy reached Menotomy on his retreat, Gen. Heath had assumed command of the militia, and the fighting there was perhaps the severest of the day. Dr. Warren kept his place near Heath, and a pin was struck from his head by a musket-ball. During the next six weeks he was indefatigable in urging on the military preparations of the New England colonies. At the meeting of the Provincial congress at Watertown, 31 Nay, he was unanimously chosen its president, and thus became chief executive officer of Massachusetts under this provisional government. On 14 June he was chosen second major-general of tile Massachusetts forces, Artemas Ward being first. On the 16th he presided over the Provincial congress, and passed the night in the transaction of public business. The next morning he met the committee of safety at Gen. Ward's headquarters on Cambridge common, and about noon, hearing that the British troops had .landed at Charlestown, he rode over to Bunker Hill. It is said that both Putnam and Prescott successively signified their readiness to take orders from him, but he refused, saying that he had come as a volunteer aide to take a lesson in warfare under such well-tried officers. At the final struggle near Prescott's redoubt, as he was endeavoring to rally the militia, Gen. Warren was struck in the head by a musket-ball and instantly kilted. His remains were deposited in the tomb of George R. Ninot in the Granary burying-ground, whence they were removed in 1825 to the Warren tomb in St. Paul's church, Boston. In 1855 they were again removed to Forest Hills cemetery, where they now repose. Dr. Warren's wife died, 28 April, 1773, leaving four children. After the death of their father they were left in straitened circumstances until in April, 1778, Gen. Benedict Arnold, who had conceived a warm friendship for Dr. Warren while at Cambridge, came to their relief. Arnold contributed $500 for their education, and succeeded in obtaining from congress the amount of a major-general's half-pay, to be applied to their support from the date of the father's death until the youngest child should be of age. The best biography of Dr. Warren is by Richard Frothingham, "Life and Times of Joseph Warren" (Boston, 1865).--His brother, John, physician, born in Roxbury, Mass., 27 July, 1753; died in Boston, Mass., 4 April, 1815, was graduated at Harvard in 1771, studied medicine for two years with his brother Joseph, and then began practice in Salem, where he attained rapid success. He attended the wounded at the battle of Bunker Hill, where he received a bayonet-wound in endeavoring to pass a sentry in order to see his brother. Soon afterward he was appointed hospital surgeon, and in 1776 he accompanied the army to New York and New Jersey. He was at Trenton and Princeton, and from 1777 till the close of the war was superintending surgeon of the military hospitals in Boston. For nearly forty years he occupied tile foremost place among the surgeons of New England. In 1780 he demonstrated anatomy in a series of dissections before his colleagues, and in 1783 he was appointed professor of anatomy and surgery in the newly established medical school at Harvard. He was first president of the Massachusetts medical society, retaining the office from 1804 till his death. He was also president of the Agricultural society and of the humane society. He frequently made public addresses, and in 1783 was the first Fourth-of-July orator in Boston. Besides "Memoirs" addressed to the American academy, "Communications" published by the Massachusetts medical society, an "Address" to the Freemasons, in whose lodge he was a grand-master, and articles in the "Journal of Medicine and Surgery," he was the author of "Mercurial Practice in Febrile Diseases." See his life by James Jackson (Boston, 1815), and by his son Edward (1873). -- -- Edited AC American Biography Copyright© 2001 by VirtualologyTM A resolution Broadside dated April 23, 1775, the very day Warren succeeded John Hancock as President of the Provincial Congress. "Resolved, that the following establishment of forces now immediately to be raised for the Recovery and Preservation of our undoubted Rights and Liberties, be as follows…" Boldly signed Jos: Warren, President P. T. Research Links Bunker Hill Exhibit | Biography | Joseph Warren ... Roxbury in 1741, son of Joseph and Mary (Stevens) Warren. He graduated from Harvard in ... volunteer in the battle at Bunker Hill in which he was killed... Bunker Hill, Battle of ... forced to retreat to Bunker Hill, leaving the battlefield ... could sell them another hill at the same price ... spot where Maj. Gen. Joseph Warren fell just as... The Battle of Bunker Hill ... Prescott, General Israel Putnam and Joseph Warren. These generals were fairly skilled in combat. Here is the account of Bunker Hill. On June 16, 1775 (at ... darter.ocps.k12.fl.us/classroom/revolution/bunker.htm - 4k - Cached - Similar pages A Journey towards Freedom ... order was to capture Bunker and Breed's Hill and ... firing toward Breed's Hill. At noon the ... from organ pipes. Fortunately, Joseph Warren and 300 volunteers... Writing Activity Students will research early newspapers (Internet search) and write a news article on an event that occurred during the respective time. They may choose the Boston Massacre, the Boston Tea Party and the Battles of Lexington and Concord or another major event described in the book, or, an event that occurred during the Road to the Revolution and tell it from the perspective of a Loyalist or a Patriot. American Revolutionary Newspapers Ben Franklin's Pennsylvania Gazette January 2, 1750 The Boston Gazette Monday, October 7, 1776 Massachusetts Centinel Saturday, April 24,1790 Websites JOHNNY TREMAIN: The Revolutionary War http://www.macomb.k12.mi.us/wq/webQ97/REVOLUT.HTM James Otis, biography http;//www.nndb.com/people/353/000049206 James Otis, biography. http://www.u-s-history.com/pages/h1256.html Joseph Warren, biography. http://www.u-s-history.com/pages/h1256.html Paul Revere, biography. http://www.historyhowstuffworks.com Ben Franklin, biography. http://www.historyhowstuffworks.com Books Brezina, C., Looking at Literature through Primary Sources, Johnny Tremain and the American Revolution ISBN0-8239-4504-9 Heims, N., The Engaged Reader Johnny Tremain ISBN 0-7910-8831-6 Freedman, R., Give Me Liberty! ISBN 0-8234-1753-0 Hakim, J., A History of US from Colonies to Country ISBN 0-19-507750-4 Herbert, J., The American Revolution for Kids ISBN 978-1-55652-456-1 Maestro, B. Liberty or Death, The American Revolution 1763-1783 ISBN 978-0-439-89914-7 Moore, K., If you Lived at the Time of the American Revolution ISBN 0-590-67444-7 Zarnowski,M., Making Sense of History ISBN-13 978-0-439-66755-5 References: Brezina, Corona. 2004. Looking at literature through primary sources: Johnny Tremain and the American Revolution. New York: Rosen Publishing. Freedman, Russell. 2000. Give me liberty!: The story of the Declaration of Independence. New York: Holiday House. Hakim, Joy. 1993. From colonies to country. New York: Oxford University Press. Heims, Neil. 2006. The engaged reader: Reading Johnny Tremain. Philadelphia, PA: Chelsea House. Herbert, Janis. 2002. The American Revolution for kids: A history with 21 activities. Chicago: Chicago Review Press. Maestro, Betsy. 2005. Liberty or death: The American Revolution, 1763-1783. New York: Scholastic. Moore, Kay. 1997. …If you lived at the time of the American Revolution. New York: Scholastic. Zarnowski, Myra. 2006. Making sense of history: Using high-quality literature and hands-on experiences to build content knowledge. New York: Scholastic. Discussion Questions: Questions/writing 1. What point of view is this story told? Why did the author chose to tell it from this perspective? 2. Predict what might happen in this story based upon the cover of the book and the back cover description 3. Express how using fiction like Johnny Tremain will help you understand the Revolutionary War 4. Identify the main character. Who is the protagonist? 5. What is the setting? Give a detailed description. Explain how the setting is important to the story 6. Who is “Mr. Hancock”? What role did he play in early US history? 7. Give two examples of “foreshadowing” in chapter one 8. Give examples of foreshadowing used in the book. 9. What caused Johnny to lose his place in Mr. Lapham’s silver shop? 10. How do you think Dove felt as he watched Johnny when he touched the hot liquid? 11. How does Johnny spend his days after the accident? 12. Johnny Tremain has a series of cause and effects. Make a list of some of these in the first few chapters. 13. What do you see as the problem/conflict Johnny Tremain is facing? 14. Stories can have more than one plot. Describe the events in the first two chapters which lead to the first catastrophic climax.