Learning from a Father`s Mistakes

advertisement

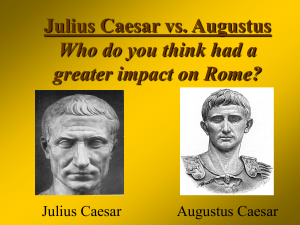

Carulli 1 David Carulli CAMS 101, Fall 2012 November 6, 2012 Learning from a Father’s Mistakes Prompt: Why did Caesar fail to establish himself as Rome's first emperor and Augustus succeed? What differences in their approach to power can you detect in the sources? Essay: During the first century BC, Rome saw two great leaders come to power: Julius Caesar and Augustus. Where Julius Caesar’s ambition drove him to ignore the Roman mos maiorum, or the way of the elders, Augustus decided to carry out his reign in a less ambitious and more respectable way, thus securing himself to become Rome’s first Emperor. Caesar ignored the mos maiorum in his handling of legislature, as well as the way in which he held his power in Rome. Augustus learned from Caesar’s mistakes, and worked to distinguish himself from Caesar, which helped him to become Rome’s first emperor. The enemies Caesar made in his reign eventually caught up to him, and it cost him his life. In his rule as consul, Caesar acted more like a Tribune of the Plebs, which both went against the mos maiorum and made him lose trust from the senate, and ultimately helped lead to his downfall. Explaining the two major ways politicians enacted laws in ancient Rome, “One group, the…optimates gained their ends by upholding the authority of the senate, while the other, dubbed populares … appealed through the tribunate to the popular assembly, and, asserting, as Caesar did, that they were liberating the people from Carulli 2 slavery to a small group, frequently overrode the senatorial majority.” (Ross Taylor 3) The optimates were a more conservative group and believed in upholding the mos maiorum, and the senate was comprised of optimates. The fact that Caesar was a part of the populares worked against him in the end, as he disregarded the mos maiorum and went straight to the plebs to propose legislature. This caused tensions between him and the senate, and of course a group of senators were the ones who assassinated him. While these actions were the most direct instigations Caesar had with the senate, there were other instances in which he neglected the great way of the ancestors. Another example of how Caesar ignored the mos maiorum is how he became dictator. According to the Roman mos maiorum, the senate would elect a dictator in times of emergency. In Julius Caesar’s case, “he assumed the title and powers of Dictator, loathed though they were from memories of Sulla, to preclude opposition, delay - and perhaps the veto” (Syme 4). Basically, he was given the status of dictator because the people loved him, and figured that he should have unopposed power in Rome. He did not necessarily demand this power by force, but he accepted it without question, which clearly displays his ambition, and his hubris. There was no urging matter that required him to become dictator, and so this is another example of how Caesar ignored the mos maiorum. One must also question Caesar’s methods of controlling the popular assemblies. Caesar grew up in a time of the Roman republic where the people who were in charge were the ones who disregarded the mos maiorum. His prime examples were leaders like Sulla, Marius, and Cinna, and he learned from their methods and became really good at ruling the people. One of the methods he took from them was to have a mob rule over the Carulli 3 public assemblies. These were actions that politicians had been conducting for the past century, but were in no way accepted as the way in which the great ancestors handled matters. It may have been the new norm, but was hardly considered the mos maiorum. Caesar made mistakes in his rise to power that cost him his life, and Augustus gained wisdom from these fatal errors. One of the ways in which Augustus differed himself from Caesar was that he never sought praise for himself. From even before Caesar’s reign, upon his return from Spain, Caesar wanted to have both his own triumph and run for consul in 59 BC. When Augustus came to power, rather than praising himself, he praised Julius Caesar. He deified his predecessor. As Peter White words it in his article “Julius Caesar in Augustan Rome,” “The cult of a divus could not tap the currents of feeling and calculation which the living strongman attracted, and even Caesar's military reputation was overshadowed by Augustus' broader political successes in projecting Roman authority abroad. But Caesar nevertheless retained an important place in the civic religion of the new regime; he was not displaced in order that Augustus might be more exalted.” (White 340) From here one can see how Augustus strategically proved himself unlike Caesar, while at the same time associating himself with his greatness. Whereas Caesar would praise himself like a God, Augustus was more humble, and instead associated his slain adopted father as a deity. It is a clever way in which he distances himself from Caesar’s unbounded ambition, but still claims to be the heir of a God-like man. This also comes after Augustus refuses to triumph himself (White 340). Idolizing Caesar was a clever way Carulli 4 to contrast himself with Caesar, but Augustus also accomplished this in the ways he ran the state. If one looks at Edwin S. Ramage’s article, “Augustus' Treatment of Julius Caesar,” one can see many instances where August deliberately differentiates himself from the idea of Caesar the tyrant. One way was that the coins he issued portrayed Augustus bareheaded on one side, and Caesar wearing a crown on the other, symbolizing his aspirations to become king (Ramage 224). The titles describing the two men also had Caesar labeled as “Pontifex Maximus” and “Dictator” with Augustus taking the more modest “Pontifex” and “Consul” (Ramage 224). One also observes differences between the two when the senate offered Augustus the dictatorship; he attempted to refuse it, and when he gained supreme command, he tried to return the power back to the people (Ramage 226). As explained already, Caesar made no such attempts; in fact he behaved in quite the opposite manner. Ramage also lists a slew of other ways in which Augustus differed himself from Caesar when looking at Augustus’s own writings, the Res Gestae: “[In the Res Gestae ] there is a continuing emphasis on the justice of Augustus' actions and the legitimacy of his position in the state. He avenged his father by lawful means; he resurrected many defunct traditions by passing new laws. It is tempting to imagine that in these instances the reader is meant to think of a Caesar who brought an illegal civil war against the state and undermined tradition by adopting the perpetual dictatorship. Augustus emphasizes the scrupulous legality of his political position at all times. His rise to power was completely legal and just: the senate made him one of them by decree and gave him the imperium; the Republic ordered him to carry Carulli 5 out the duties of propraetor; the people elected him consul and then triumvir.” (Ramage 228) From this analysis, one can clearly see multiple examples of how Augustus not only respected the mos maiorum, but even attempted to bring the state back to values held long before his own time. Augustus did not clutch on to power like Caesar did; power was thrust upon him, and he only reluctantly accepted it. Augustus knew what mistakes Caesar had made, and he avoided making the same ones, which allowed him to secure the title of Rome’s first emperor. When one observes all of the evidence from the time, one can see how Caesar’s neglect of the mos maiorum both caused his reign to come to an end, and set up the precedent for Augustus’ rise to power. Caesar upset the senate by proposing legislature to the plebs without consulting it first. He repeatedly displayed his ambition, and the Romans feared ambitious men. He controlled the assemblies in illegal and dishonorable manners. Augustus saw how all of this made Caesar’s enemies grow more suspicious and slay him in cold blood. This gave Augustus the wisdom to make the public believe that he would rule in just the opposite way Caesar had. He was humble rather than ambitious; he conducted matters legally; he tried to give power back to the senate; he tried to restore the mos maiorum. Carulli 6 Sources: Ramage, Edwin S. "Augustus' Treatment of Julius Caesar." Historia: Zeitschrift Für Alte Geschichte 34.2 (1985): 223-45. JSTOR. Web. 6 Nov. 2012. <http://www.jstor.org/stable/4435922>. Ross Taylor, Lily. "Caesar and the Roman Nobility." Transactions and Procedings of the American Philological Association 73 (1942): 1-24. JSTOR. Web. 6 Nov. 2012. <http://www.jstor.org/stable/283534>. Syme, Ronald. "Caesar, the Senate, and Italy." Papers of the British School at Rome 14 (1938): 1-31. JSTOR. Web. 06 Nov. 2012. <http://www.jstor.org/stable/40310446>. White, Peter. "Julius Caesar in Augustan Rome." Phoenix 42.4 (1988): 334-56. JSTOR. Web. 6 Nov. 2012. <http://www.jstor.org/stable/1088658>.