Melissa LaCasse Futuristic Fictions Research Paper Steampunk

advertisement

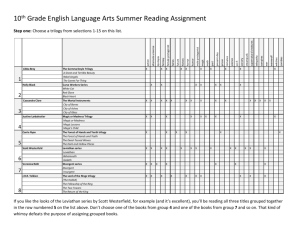

Melissa LaCasse Futuristic Fictions Research Paper Steampunk Clad in top hats and brown leather trench coats, armed with ray guns and blunderbusses, and decked out head to toe in gears and goggles, steampunks are becoming an ever-more common sight in the science fiction community. The exact purpose of steampunk is often difficult to describe, even by the most seasoned of punks. Some view it as a way of rejecting the mass-produced consumerism of today’s society by returning to the roots of modern technology, just before the turn of the century. Some embrace the gritty world of days long gone, when one’s worth was determined by one’s will. Others use it as an excuse to tinker with analog technology and 19th-century aesthetics to their heart’s content. Still others see steampunk as nothing more than a fun hobby with classy costumes. Whatever the case, though steampunk is a relatively young genre, it has recently been growing in popularity and is well on its way to becoming the next great sci-fi trend. With so many different views on just what it means to be steampunk, it is very hard to define it as a genre. In its most basic form, steampunk is characterized by a focus on an alternative history, a past in which technology, and by extension society, took a different path. This alteration is usually based during or around the Victorian era. Common themes include technological advances being made ahead of schedule and hence designed using the materials and science of the time—for example, a clockwork laptop—or having a different invention entirely take the stage instead, such as airships instead of airplanes. The appeal of 19th-century steam-powered technology is easy to identify. Steampunk Magazine describes it best in their very first issue, in an article titled “What, then, is Steampunk? Colonizing the Past so we can Dream the Future,” which says that these machines were “real, breathing, coughing, struggling and rumbling parts of the world…The technology of steampunk is natural; it moves, lives, ages and even dies.” The same article also does a great job of capturing the attitude of the modern steampunk: We seek inspiration in the smog-choked alleys of Victoria’s duskless Empire. We find solidarity and inspiration in the mad bombers with ink stained cuffs, in whip-wielding women that yield to none, in coughing chimney sweeps who have escaped the rooftops and joined the circus. (5) While this motley assembly of traits is highly characteristic of the genre, this exact interpretation may not be true of every steampunk, because no matter how steampunk is defined, one of the more basic rules of the genre is to be creative while playing with history. Despite being set in and influenced by ages long past, steampunk as a genre is rather young. According to Cory Gross’s five-part history of steampunk for the website Voyages Extraordinaire, although there were a few notions of steampunk earlier in the century, it wasn’t until the 1970s and 80s that the genre was truly born. Author K. W. Jeter is responsible for coining the word “steampunk”—being like cyberpunk, but with elements from the past instead of from the future—to describe the sort of Victorian fantasies that he and his friends were starting to toy around with. The real turning point in the birth of the steampunk genre was The Difference Engine in 1990, by acclaimed cyberpunk authors William Gibson and Bruce Sterling. The story was based on a simple idea: what if Charles Babbage had succeeded in creating his analog computer during the Victorian Era? The result was a world in which the Information Age was happening at the same time as the Steam Age, for better and for worse. Gibson was reluctant to label this work as officially steampunk, and didn’t think that the word steampunk would catch on. (Gross, “The Birth of Steampunk”) But catch on it did, and it continued to lurk around the science fiction world in various forms throughout the 90s, until two important works came out in 1999. One was the movie Wild Wild West, based on the television show of the same name from the 1960s. Though the movie was a flop, it did a decent enough job of demonstrating the basic steampunk aesthetic that it stuck around the public consciousness. In the same year, Alan Moore and Kevin O’Neill came out with a comic book called The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen, in which characters from various works of Victorian fiction team up to serve England using their supernatural abilities. The League did a much better job of representing steampunk, and helped to give it a powerful boost into mainstream science fiction. (Gross, “A Genre Comes of Age”) Given its shared roots with cyberpunk, perhaps it’s fitting that the internet quickly became the breeding ground for the rapidly emerging steampunk subculture. A simple search produces countless blogs, forums, tutorials, articles, and more. Once steampunks had become a bit more organized and began recognizing the do-it-yourself aspects of punk, the genre truly began to explode. Especially in the past year, steampunk has grown exponentially into the multifaceted and ever-expanding wonderful mess that it is today. (Gross, Putting the Punk into Steampunk”). One of my first introductions into the world of steampunk, though I didn’t know it at the time, was Kenneth Oppel’s Airborn and its sequels, Skybreaker and Starclimber. Published in 2004, Airborn is set in an alternate past, in which airships dominate the skies in lieu of airplanes, which have not been invented. A boy named Matt Cruse works aboard one of these airships, which are lifted by a fictional (and considerably less flammable) gas known as hydrium. During one of the airship’s voyages from Lionsgate City (known in our world as Vancouver) to Sydney, Australia, Matt becomes caught up in an adventure involving sky pirates, shipwreck, and mysterious creatures living high in the Earth’s atmosphere. Airborn was written a few years before the steampunk movement started to become popular, but the setting and the themes throughout the story clearly mark it as steampunk. Around the same time that Airborn came out, the anime world was officially introduced to steampunk through Katsuhiro Otomo’s Steamboy. Otomo is perhaps best known for his 1988 film, Akira, which was a huge factor in the spread of anime beyond Japan, and Steamboy definitely lives up to Otomo’s reputation. It’s the story of Ray Steam, a young inventor whose father and grandfather discovered a revolutionary new way to store and use steam energy, called the Steam Ball. It’s quickly revealed that the wonders of the Steam Ball can be extremely dangerous if placed in the wrong hands, and Ray finds himself having to protect the secret of the Steam Ball while saving London and trying to keep his family in one piece. Every inch of this movie is pure steampunk, especially the much-explored question of the nature and purpose of science. Though at first glance it might not seem very steampunk, the 2004 movie Sky Captain and the World of Tomorrow demonstrates the genre in a very interesting way. The story is set in the late 1930s and follows an adventurous female reporter named Polly Perkins, and cheeky ace aviator Joseph “Sky Captain” Sullivan, in their search to find out who’s behind a fleet of giant robots attacking New York City. As they travel across the globe, Polly and Joe also encounter aircraft with wings that flap, ray guns, holograms, rocket ships, airborne secret bases, and airplanes that can transform submarines in a matter of seconds. These futuristic inventions are highly characteristic of steampunk, as they clearly do not belong in 1939, but if the anachronistic gadgets aren’t enough to prove the steampunk soul of this movie, it also challenges social norms of the time, featuring strong female characters who refuse to play anything less than lead roles. Additionally, the movie was designed to be reminiscent of the epic adventure movies that were made in the early days of film, so even at its very core, Sky Captain is a wonderful example of the fun side of futuristic science that steampunks adore. Scott Westerfeld, who was already a well-established writer of young adult sciencefiction before the steampunk genre started gaining momentum, published a novel titled Leviathan during the boost of popularity in 2009. It takes place at the start of an alternate version of World War I, where the Germans and Austro-Hungarians are armed with advanced steam-powered machines and are referred to as Clankers, while on the British side there are the Darwinists, who fight with genetically fabricated creatures. One of the two main characters, Alek, is a perfect example of altered history because although he didn’t exist in our timeline, in the world of Leviathan, he finds himself on the run as heir to the Austro-Hungarian empire after his parents’ deaths spark the beginning of the Great War. On the opposite side of the conflict, there’s Deryn, a girl with a wonderfully colorful vocabulary who disguised herself as a boy in order to enter the British Air Service. Westerfeld is a writer who consistently puts a great deal of thought and research into his books, which is one of the reasons that Leviathan works so well as part of the genre. Unlike most of my other examples, this book was written and marketed as officially steampunk, and with Westerfeld’s historical know-how and attention to detail, Leviathan certainly earns its place as a fantastic piece of steampunk literature. The recently-released movie Sherlock Holmes, the latest adaptation of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s famous novels, is a bit questionable as to whether or not it’s really an example of steampunk. It’s certainly set in the proper time period, but that’s only because it’s based off of the stories, which were written in that time. Although steampunks love finding inspiration in actual Victorian literature, the story itself does not count as steampunk. However, the movie is just that; inspired. It follows a completely original plot based on the world and characters created by Doyle—Holmes and Watson, about to go their separate ways as Watson prepares for marriage, are called upon to work together one last time in order to solve a string of murders that seem to be caused by black magic. Though the movie’s plot is something new, there are dozens of references to the original stories in everything from the dialogue to the set pieces. What makes this movie so steampunk, however, is not its homage to the great work of 19th-century literature; it is the technology. The weapons and inventions of the two main antagonists are ahead of their time, but still very obviously designed and built within their era, which is a key identifier of steampunk-style gadgetry. Therefore, I count Sherlock Holmes as an example of the steampunk genre, and a good example at that. In the wake of steampunk’s newfound popularity, there has also been an inevitable negative response, from steampunks themselves as well as non-steampunks. Though a lot of the nay-saying from outside the community has simply been from those who aren’t interested in the genre, there has also been criticism from people who are interested in the idea but dislike how it’s being presented. The romanticized portrayal of the Victorian Age has been a point of contention for some, since at its surface, steampunk certainly seems to overlook the fact that most of the population of Victorian London lived in horribly difficult conditions, working their lives away while the upper classes profited from their labor. Author Cherie Priest has a response for this sort of criticism in her blog, The Clockwork Century. According to her, “with its timetravel/history-altering underpinnings, steampunk has the capacity to un-write some of the rules [of history]…It’s open to everyone — including those whose historical representation got left out, written out, or killed out of hand.” (Priest, “Steampunk”) In other words, since steampunk is a genre of history-that-never-was, steampunks are free to call attention to those underrepresented masses on whose backs the Victorian Era was built. They don’t ignore that the class inequality happened, but instead try to imagine a world in which it didn’t. This is part of the “punk” of steampunk. Many of the newer recruits to the genre aren’t aware just what it means to be punk, and instead think that steampunk is all shiny gears and clockwork, much to the annoyance of the more committed steampunks. However, the deeper you dive into the steampunk subculture, the more punk-ish things become. In his blog called Airship Ambassador, Kevin Steil ties the steampunk genre to the original punk ideals, which he says are reaction, rebellion, and resolution. He points out how steampunk can be considered a response to “social injustices of the past and present, or current inconsiderate and uncompassionate behaviors, or the effects of monotonous, mass-produced, corporate design” and how steampunks use their creativity and intellectualism to address those issues (Steil, “Steampunk is…Reaction, Rebellion, Resolution”). For many fans, steampunk is not just a genre, but a way of life, in which one must take into account the problems of the past, present, and future all at once. I’ll admit that I was drawn to steampunk for the romanticized vision of the glorious age of Victorian England. I still love the long skirts, goggles, top hats, and gears of the typical steampunk look, but now I’ve started to dig deeper into the genre. The DIY aspect, affectionately referred to as tinkering by some, is especially appealing to me, since I’ve always like doing crafts and figuring out how things work. Through steampunk, I’ve found an outlet for the tinkerer in me; so far, I’ve installed a working clock in a top hat, designed and built a steampunk-style witch’s broom, and made my own goggles from scratch. My lifelong interest in history has also found a home in the genre, and the more I learn about the past, the more I can apply it to my present interests. I listen to steampunk-inspired music, peruse steampunk blogs, and try to figure out where I can find an airship so that I can attend the steampunk conventions that take place on the other side of the country. In short, I am whole-heartedly a steampunk. In a world run by ever-more advanced technology, I’ve never quite been able to catch up with the latest gadgets, and would be just as comfortable using a typewriter as a laptop, so the moving, breathing technology of steampunk is alluring. Analog machinery makes sense to me, because I can figure out how it works without needing hundreds of circuitry diagrams. As Scott Westerfeld points out in an interview about Leviathan, modern machines are nothing more than blobjects, which means that “you can learn nothing about them by inspecting their shapes. Compare that to a steam engine, where you can SEE how it works, even feeling the heat with your hand if need be.” (Monti) Steampunk provides an answer for this disconnect between humans and our machines. It has become more than just a science fiction genre; like the machines it embraces, steampunk is a living, breathing, growing culture. Whether the current fad-like popularity lasts or not, steampunks will continue to re-examine the future by reinventing the past. Works Cited Catastrophone Orchestra and Arts Collective. “What Then, Is Steampunk? Colonizing the Past so we can Dream the Future.” Steampunk Magazine: 5. Web. 4 May 2010. Gross, Cory. “A History of Steampunk: Part III - The Birth of Steampunk.” Voyages Extraordinaire. N.p., 14 Aug. 2008. Web. 4 May 2010. <http://voyagesextraordinaires.blogspot.com///history-of-steampunk-part-iii-birthof.html>. - - -. “A History of Steampunk: Part IV - A Genre Comes of Age.” Voyages Extraordinaire. N.p., 19 Aug. 2008. Web. 4 May 2010. <http://voyagesextraordinaires.blogspot.com///ofsteampunk-part-iv-genre.html>. - - -. “A History of Steampunk: Part V - Putting the Punk into Steampunk.” Voyages Extraordinaire. N.p., 21 Aug. 2008. Web. 4 May 2010. <http://voyagesextraordinaires.blogspot.com///of-steampunk-part-v-putting.html>. Priest, Cherie. “Steampunk: What it is, why I cam to like it, and why I think it’ll stick around.” The Clockwork Century. N.p., 9 Aug. 2009. Web. 6 May 2010. <http://theclockworkcentury.com/?p=165>. Steil, Kevin. “Steampunk is...Reaction, Rebellion, Resolution.” Airship Ambassador. N.p., 18 Apr. 2010. Web. 5 May 2010. <http://airshipambassador.wordpress.com////is%e2%80%a6-reaction-rebellion-resolution/>. Westerfeld, Scott. “An Interview with Scott Westerfeld on Barking Spiders, Steampunk, and All Things Leviathan.” Interview by Joe Monti. Tor.com. N.p., 30 Oct. 2009. Web. 13 Dec. 2009. <http://www.tor.com/.php?option=com_content&view=blog&id=58190>. Examples of Steampunk Oppel, Kenneth. Airborn. New York: HarperCollins, 2004. Print. Sherlock Holmes. Guy Ritchie. Warner Bros., 2009. Film. Sky Captain and the World of Tomorrow. Kerry Conran. Paramount, 2004. Film. Steamboy. Katsuhiro Otomo. Sony Pictures, 2004. Film. Westerfeld, Scott. Leviathan. Illus. Keith Thompson. New York: Simon Pulse, 2009. Print.