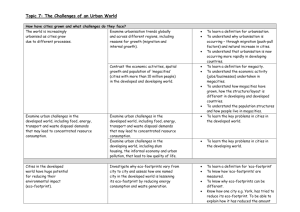

0. Summary: Mega-trends Urbanisation and changes in consumption

advertisement