It`s thirty years now since I first went to Saudi Arabia

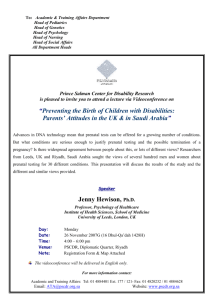

advertisement