strategic planning in samaritan centers

advertisement

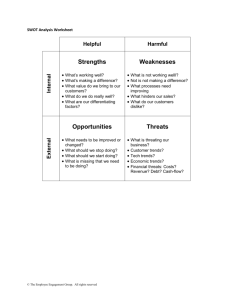

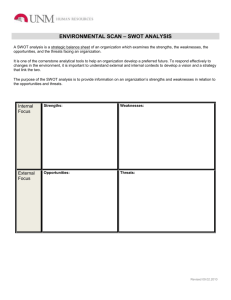

I.J.3 STRATEGIC PLANNING IN SAMARITAN CENTERS INTRODUCTION Strategic planning is different from ordinary planning. In ordinary planning, there is usually some goal to be reached or strategy to be implemented that has already been established. A plan tells you the steps to take in order to reach your goal or implement your strategy. Strategic planning has a more ambitious aim. The term, “strategic market planning” which is sometimes used, gets at this larger picture. Think of it this way: a Samaritan Center serves people in its community. These people (clients, students, sponsors) and this community (congregations, businesses, and organizations) are the Center’s market. The Center has services – counseling, education, consultation – which it wants people in the community to use in exchange for their money and support. The Center is not alone in this effort. Other counseling agencies and professionals compete for exchanges with the same clients and organizations. Strategic planning is a comprehensive, integrated effort to enhance the Center’s position in a competitive environment. It is a total organizational push that focuses the Center’s mission and capabilities in relation to its potential for service. This whole package of thinking, data gathering, analysis, and commitment to specific plans is called “strategic planning.” The written strategic plan documents the strategic planning process. It functions like a map for the Center to follow as it tries to implement the overall plan. But, like maps that have to be continually updated, the written plan must be revised periodically because the Center is in a changing environment and it keeps changing. There are at least three main ways Samaritan Centers can benefit from strategic planning. One is the benefit of systematic reappraisal of Center mission and services, because this way of planning deals with the health of the whole organism rather than with symptoms. A Center that is not in crisis can best use strategic planning as a means of testing purpose and goals and of establishing priorities for growth and change. A second benefit is getting a reading on how well the Center is doing. In what ways are its mission and primary task being properly fulfilled, and what are the weak spots? Even in thriving Centers, the strategic planning process can reveal gaps in programming and opportunities for growth that invigorate the organization. A third benefit is that this planning process encourages board and staff leaders to establish a renewed sense of direction. A strategically based plan reassures those in charge that their efforts are leading toward a future that has been examined and translated into manageable goals and programs. It is also reassuring to know that adjustments can be made and the future renegotiated through a process that is structured as a learning experience. The Samaritan Institute 157 I.J.3 Strategic Planning in Samaritan Centers, page 2 STEPS IN STRATEGIC PLANNING The steps listed in this outline are only an introduction to strategic planning, not a detailed set of instructions for conducting strategic planning in your Center. When you are ready to conduct the planning process, we suggest that you use a resource such as Peter Drucker, The Five Most Important Questions: A Participant’s Workbook, The Drucker Foundation, published by JosseyBass, 1993. Also, we recommend the use of someone with experience and expertise in strategic planning to guide the process. What we offer below is an overall perspective. 1. Evaluate your mission. Most Centers have written mission statements. Take a close look at this document: does it reflect in simple, direct terms what the Center is and does? If Center leaders have not examined the mission statement recently, it probably will need revision to reflect current thinking and circumstances. Start with your mission statement. 2. Define unmet needs. The Center is currently serving some of the needs of people in the community. But what other needs are not being met, either by the Center or by anyone else? You should seek objective data in making this assessment, not relying solely on casual observations or hunches. Bring in knowledgeable people from the community to help you with this. Ask yourselves: What community needs match our Center’s mission? Then narrow it down: Which of these needs fit our capabilities and resources? You may find that, instead of adding a new market, you should do more of what you are already doing. 3. Evaluate internal strengths and weaknesses. This step, and the one following, are commonly referred as a SWOT analysis – strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, threats – or as the internal and external audit. Strengths and weaknesses have to do with Center capabilities: what does it do well and not so well; what talents and training are represented on the staff and where there are gaps in talent and training; in what ways does the board excel and where is it deficient; which services are of high quality and which ones do not meet the standard; etc. The Center’s larger capabilities also need to be assessed: in what ways is it flexible, adaptive, and innovative in meeting current challenges and opportunities, and in what ways is it enmeshed in inefficiencies and dysfunction? Audit your current strengths and weaknesses. 4. Assess environmental (community) opportunities and threats. Knowing what’s out there in the community is just as important as understanding internal capabilities. For example, does your Center have educational and consultation services that congregations can use? Is there a way to balance managed care business with fee-for-service business? What are the threats to Samaritan identity posed by secular therapists who market their own “spiritual” services? Is there an opportunity to package some of your services differently so that people with busy schedules and new lifestyles can more easily use them? So much is changing in the external environment, that Centers must assess what is out there that represents new opportunities and emerging threats. Do the external audit. 5. Set objectives and goals. You have reached a critical point in the strategic planning process. What has the data gathering and analysis of the first four steps yielded? Does the evidence mostly confirm the Center’s current posture, or is repositioning called for? The Samaritan Institute 158 I.J.3 Strategic Planning in Samaritan Centers, page 3 Strategic planning can be used for both purposes. For example, a Center that decides it is on the right track has the option of mapping out objectives that will lead to greater effectiveness and efficiency, such as upgrading its marketing efforts or developing a new service initiative. By contrast, a Center that sees the need for more radical change may seek objectives that call for the restructuring of its services or moving to a new style of executive leadership. The task now is to set those objectives. What do you want to achieve? What will the end product look like? How will you know when you have achieved your goal? Objectives are statements of intent about meeting specified needs. They become meaningful if they fit the Center’s mission, and reflect the internal and external strengths, opportunities, and constraints that have emerged in the SWOT analysis. Objectives pulled out of thin air rarely are worthwhile or achievable. Set your objectives. 6. Select strategies. Strategies are like game plans – for example, deciding an overall approach to playing and winning the game. In this case, the game is achieving your stated objectives. What ideas and actions will guide your use of your staff, the services of the board, program capabilities, and community sponsors in achieving the desired objective? Strategic thinking goes beyond simply determining a method and timetable. A strategy encompasses a number of possible tactical maneuvers and implementing procedures. It is the thrust of the action that matters most in strategic thinking and planning. 7. Design programs. By program we mean activities that implement strategies. For example, if the objective of Center A is to diversify its services, its strategy to accomplish this objective may be to build a model for diversification based on successful practices in other Samaritan Centers. A possible program design for pursuing this strategy might then look like this: a) call the Samaritan Institute to get information on Centers that do successful diversification; b) gather data from Centers B, C, and D; c) summarize data and propose two or three options for applying what has been learned to the needs of Center A; d) choose one of the options as the best choice to follow. Programs should be designed to work, not just to look good. An imperfect program design that a Center can use is better than an ideal one that is beyond its capacity. 8. Implementation and evaluation. One might think that strategic planning stops when plans have been made and put into action. But that is not the case. Peter Senge describes “learning organizations” as those in which leaders and managers pay attention to what is happening inside and outside the organization to develop new thinking and better practices. There is constant learning and redesign. This is the point about strategic planning: it is never a done deal. As the Center examines its mission and its capabilities, and as it seeks to implement more effective service to its community, new information emerges that modifies what has been planned. There is a continual feedback loop. The Samaritan Institute 159 I.J.3 Strategic Planning in Samaritan Centers, page 4 The chart below diagrams the process we have been describing. The steps in a strategic planning process are shown in circles that overlap to suggest interaction as well as progression. As you move from left to right, there are two main packages of activity. The first four circles not only overlap to show interaction but also delineate the data gathering and analysis part of the planning process. The next four circles, also interactively connected, delineate the application part of the process. The two large arrows, top and bottom, point in opposite directions, suggesting how the whole process feeds back upon itself, the end results leading to reassessment of mission, community needs, strengths and weaknesses, and so on. All of this is to show that strategic planning is best understood as a process, not a product. I MISSION Who we are What we do Whom we serve II COMMUNITY Unmet needs III INTERNAL AUDIT Strengths Weaknesses V OBJECTIVES Desired outcomes IV EXTERNAL AUDIT Opportunities Threats VI STRATEGIES To reach objectives VII PROGRAMS To implement strategies VIII EVALUATION Sources: David Appel, Ph.D. Lectures at the Samaritan Institute, 1988 George S. Day, Strategic Market Planning, 1987 H. J. Bryce, Financial & Strategic Management for Nonprofit Organizations, 1987 The Samaritan Institute 160