1.0 Great Awakening.doc

The Great Awakening

A Decline in Religious Devotion

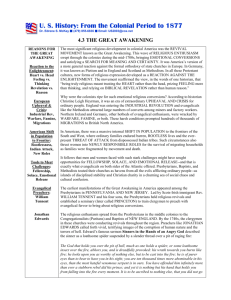

In the early 1700s, south of New England, the Anglican Church was weak, its ministers uninspiring, and many families remained "unchurched." A historian of religion has estimated that only one adult in fifteen was a member of a congregation. Although this figure may understate the impact of religion on community life, it helps keep things in perspective.

The Puritan churches of New England also suffered declining membership and falling attendance at services, and many ministers began to warn of Puritanism's "declension," pointing to the "dangerous" trend toward the "evil of toleration." By the second decade of the eighteenth century only one in five New Englanders belonged to an established congregation. When

Puritanism had been a sect, membership in the church was voluntary and leaders could demand that followers testify to their religious conversion. But when Puritanism became an established church, attendance was expected of all townspeople, and conflicts inevitably arose over the requirement of a conversion experience. An agreement of 1662, known as the Half-Way Covenant, offered a practical solution: members' children who had not experienced conversion themselves could join as

"half-way" members restricted only from participation in communion. Thus the Puritans chose to manage rather than to resolve the conflicts involved in becoming an established religion. Tensions also developed between congregational autonomy and the central control that traditionally accompanied the establishment of a state church. In 1708 the churches of Connecticut agreed to the

Saybrook Platform, which enacted a system of governance by councils of ministers and elders rather than by congregations. This reform also had the effect of weakening the passion and commitment of church members.

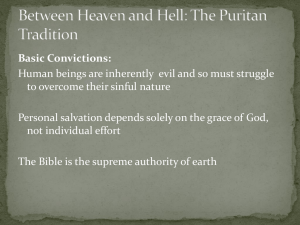

In addition, an increasing number of Congregationalists began to question the strict

Calvinist theology of predestination, the belief that Cod had predetermined the few men and women who would be saved in the Second Coming. In the eighteenth century many Puritans turned to the much more comforting idea that God had given people the freedom to choose salvation by developing their faith and good works, a theological principle known as Arminianism (for the sixteenth-century Dutch theologian Jacobus Arminius). This belief was in harmony with the

Enlightenment view that men and women were not helpless pawns but rational beings who could actively shape their own destinies. Also implicit in these new views was an image of God as a loving rather than a punishing father. Arminianism became a force at Harvard in the early eighteenth century, and soon a new generation of Arminian ministers began to assume leadership in

New England's churches. These "liberal" ideas appealed to groups experiencing economic and social improvement, especially commercial farmers, merchants, and the comfortable middle class with its rising expectations. But among ordinary people, especially those in the countryside where traditional patterns lingered, there was a good deal of opposition to these "unorthodox" new ideas.

The Great Awakening

The first stirrings of a movement challenging this rationalist approach to religion occurred during the I730s, most notably in the movement sparked by Rev. Jonathan Edwards in the community of Northampton, in western Massachusetts. As the leaders of the community increasingly devoted their energies to the pursuit of wealth, the enthusiasm had seemed to go out of religion. The congregation adopted rules allowing church membership without evidence of a

conversion experience and adopted a seating plan for the church that placed wealthy families in the prominent pews, front and center. But the same economic forces that made the "River Gods," as the wealthy landowners of the Connecticut Valley were known-impoverished others. Young people from the community's poorer families grew disaffected as they were forced to postpone marriage because of the scarcity and expense of the land needed to set up a farm household. Increasingly they refused to attend church meeting, instead gathering together at night for "frolics" that only seemed to increase their discontent.

The Reverend Edwards made this group of young people his special concern. Believing that they needed to "have their hearts touched," he preached to them in a style that appealed to their emotions. For the first time in a generation, the meeting house shook with the fire and passion of

Puritan religion. "Before the sermon was done," one Northampton parishioner remembered one notable occasion, "there was a great moaning and crying through the whole house, What shall I do to be saved? Oh I am going to Hell!-Oh what shall I do for Christ?" Religious fever swept through the community, and church membership began to grow. There was more to this than the power of one preacher, for similar revivals were soon breaking out in other New England communities, as well as among German pietists and Scots-Irish Presbyterians in Pennsylvania. Complaining of

"spiritual coldness," people abandoned ministers whose sermons read like rational dissertations for those whose preaching was more emotional.

These local revivals became an inter colonial phenomenon thanks to the preaching of

George Whitefield, an evangelical Anglican minister from England, who in 1738 made the first of several tours of the colonies. By all accounts, his preaching had a powerful effect. Even Benjamin

Franklin, a religious skeptic, wrote of the "extraordinary influence of [Whitefield's] oratory" after attending an outdoor service in Philadelphia where 30,000 people crowded the streets to hear him.

Whitefield began as Edwards did, chastising his listeners as "half animals and half devils," but he left them with the hope that God would be responsive to their desire for salvation. "The word was sharper than a two-edged sword," Whitefield wrote after one of his sermons. The bitter cries and groans were enough to pierce the hardest heart. Some of the people were as pale as death; others were wringing their hands; others lying on the ground; others sinking into the arms of their friends; and most lifting their eyes to heaven and crying to God for mercy. They seemed like persons awakened by the last trumpet, and coming out of their graves to judgment." Whitefield avoided sectarian differences. "God help us to forget party names and become Christians in deed and truth," he declared.

Historians of religion consider this widespread colonial revival of religion, known as the

Great Awakening, to be the American version of the second phase of the Protestant Reformation.

Religious leaders condemned the laxity, decadence, and officialism of established Protestantism and reinvigorated it with calls for piety and purity. People undergoing the economic and social stresses of the age, unsure about their ability to find land, to marry, to participate in the promise of a growing economy, found relief in religious enthusiasm.

In Pennsylvania, two important leaders of the Awakening were William Tennent and his son Gilbert Tennent. An Irish-born Presbyterian, the elder Tenant was an evangelical preacher who established a school in Pennsylvania to train like-minded men for the ministry. Tenant sent a large number of enthusiastic ministers into the field, and his lampooned "Log College" ultimately evolved into the College of New Jersey, later Princeton University, founded in 1746. In the early

1740s, disturbed by what he called the "presumptuous security" of the colonial church, Tenant toured with Whitefield and delivered the famous sermon "The Dangers of an Unconverted

Ministry," in which he called upon Protestants to examine the religious convictions of their own

ministers. Among Presbyterians, open conflict broke out between the revivalists and the old guard, and in some regions the church hierarchy divided into separate organizations.

In New England similar factions known as the New Lights and the Old Lights accused each other of heresy. The New Lights railed against Arminianism, branding it a rationalist heresy, and called for a revival of Calvinism. The Old Lights condemned emotional enthusiasm as part of the heresy of believing in a personal and direct relationship with God outside the order of the church.

Itinerant preachers appeared in the countryside stirring up trouble. The followers of one traveling revivalist burned their wigs, jewelry, and fine clothes in a bonfire, then marched around the conflagration, chanting curses at their opponents, whose religious writings they also consigned to the flames. Many congregations split into feuding factions, and ministers found themselves challenged by their newly awakened parishioners. In one town members of the congregation voted to dismiss their minister, who lacked the emotional fire they wanted in a preacher. When he refused to vacate his pulpit, they pulled him down roughed him up, and threw him out the church door.

Never had there been such turmoil in New England churches.

The Great Awakening was one of the first "national" events in American history. It began somewhat later in the South, developing first in the mid-1740s among Scots-Irish Presbyterians, then achieving its full impact with the organization work of Methodists and particularly Baptists in the 1760s and early 1770s. The revival not only affected white Southerners but introduced many slaves to Christianity for the first time. Local awakenings were frequently a phenomenon shared by both whites and blacks. The Baptist churches of the South in the era of the American Revolution included members of both races and featured spontaneous preaching by slaves as well as masters.

In the nineteenth century white and black Christians would go their separate ways, but the joint experience of the eighteenth-century Awakening shaped the religious cultures of both groups.

Many other "unchurched" colonists were brought back to Protestantism by the Great

Awakening. But a careful examination of statistics suggests that the proportion of church members in the general population probably did not increase during the middle decades of the century. While the number of churches more than doubled from 1740 to 1780, the colonial population grew even faster, increasing by a factor of three. The greatest impact was on families already associated with the churches. Before the Awakening, attendance at church had been mostly an adult affair, but throughout the colonies the revival of religion had its deepest effects upon young people, who flocked to church in greater numbers than ever before. For years the number of people experiencing conversion had been steadily falling, but now full membership surged. Church membership previously had been concentrated among women, leading Cotton Mather, for one, to speculate that perhaps women were indeed more godly. But men were particularly affected by the Great

Awakening, and their attendance and membership rose. "God has surprisingly seized and subdued the hardest men, and more males have been added here than the tenderer sex," wrote one

Massachusetts minister.

Great Awakening Politics

The Awakening appealed most of all to groups who felt bypassed by the economic and cultural development of the British colonies during the first half of the eighteenth century.

Religious factions did not divide neatly into haves and have-nots, but the New Lights tended to draw their greatest strength from small farmers and less prosperous craftsmen. Many members of the upper class and the comfortable "middling sort" were shocked by the excesses of the Great

Awakening, viewing them as indications of anarchy, and became even more committed to rational religion.

A number of historians have suggested that the Great Awakening had important political implications. In Connecticut, for example, Old Lights politicized the religious dispute by passing a series of laws in the General Assembly designed to suppress the revival. In one town, separatists refused to pay taxes that supported the established church and were jailed. New Light judges were thrown off the bench, and others were denied their elected seats in the assembly. The arrogance of these actions was met with popular outrage, and by the 1760s the Connecticut New Lights had organized themselves politically and, in what amounted to a political rebellion, succeeded in turning the Old Lights out of office. These New Light politicians would provide the leadership for the American Revolution in Connecticut.

Such direct connections between religion and politics were relatively rare. There can be little doubt, however, that for many people the Great Awakening offered the first opportunity to actively participate in public debate and public action that affected the direction of their lives.

Choices about religious styles, ministers, and doctrine were thrown open for public discourse, and ordinary people began to believe that their opinions actually counted for something. Underlying the debate over these issues were insecurities about warfare, economic growth, and the development of colonial society. The Great Awakening empowered ordinary people to question their leaders, an experience that would prove critical in the political struggles to come.

On all the colonial churches, religion was less fervid in the early eighteenth century than it had been a century earlier, when the colonies were first planted. The Puritan churches in particular sagged under the weight of two burdens: their elaborate theological doctrines and their compromising efforts to liberalize membership requirements. Churchgoers increasingly complained about the "dead dogs" who droned out tedious, overerudite sermons from Puritan pulpits. Some ministers, on the other hand, worried that many of their parishioners had gone soft and that their souls were no longer kindled by the hellfire of orthodox Calvinism. Liberal ideas began to challenge the old-time religion, and some worshipers now proclaimed that human beings were not necessarily predestined to damnation but might save themselves by good works. A few churches grudgingly conceded that spiritual conversion was not necessary for church membership. Together, these twin trends toward clerical intellectualism and lay liberalism were sapping the spiritual vitality from many denominations.

The issues included: [1] control of ministry and theology [2] who shall preach [3] what is orthodox. On the one side were established ministers trained in England, on the other, younger men trained in America. The ministry was a career, not a calling. The New Lights were anti structure and procedures, and they opposed control of American churches by England. [e.g. Its not OK till the church says it is. Who says?] This led to [1] a breakdown of deference [2] encouraged notions of equality [3] favored religious freedom and toleration [4] freedom of thought [5] disestablishment of established churches [6] an emotional rather than intellectual response to God [6] promoted humanitarian reform [7] promoted educational improvement. Two heresies were Antinomianism

[the belief that grace and personal revelation from God supersedes all divine and human laws] and

Arminianism [contrary to orthodox Calvinism humans can demonstrate free will and their salvation is not predestined]. This was supplemented by the Enlightenment, which stressed mans capabilities and his ability to understand the world [the secrets of the universe] which ran on natural laws like

Newtons gravity. Science attacks the Divine Right of Kings, and nothing could be explained simply by saying it was Gods will.

The stage was thus set for a rousing religious revival. Known as the Great Awakening, it exploded in the 1730s and 1740s and swept through the colonies like a fire through prairie grass.

The Awakening was first ignited in Northampton, Massachusetts, by a tall, delicate, and intellectual pastor, Jonathan Edwards. Perhaps the deepest theological mind ever nurtured in America, Edwards proclaimed with burning righteousness the folly of believing in salvation through good works and affirmed the need for complete dependence on God's grace. Warming to his subject, he painted in lurid detail the landscape of hell and the eternal torments of the damned. "Sinners in the Hands of an Angry God" was the title of one of his most famous sermons. He believed that hell was "paved with the skulls of unbaptized children."

Edwards's preaching style was learned and closely reasoned, but his stark doctrines sparked a warmly sympathetic reaction among his parishioners in 1734. Four years later the itinerant English parson George Whitefield loosed a different style of evangelical preaching on America and touched off a conflagration of religious ardor that revolutionized the spiritual life of the colonies. A former alehouse attendant, Whitefield was an orator of rare gifts. His magnificent voice boomed sonorously over thousands of enthralled listeners in an open field. One of England's greatest actors of the day commented enviously that Whitefield could make audiences weep merely by pronouncing the word Mesopotamia and that he would "give a hundred guineas if I could only say

'O!' like Mr. Whitefield."

Triumphally touring the colonies, Whitefield trumpeted his message of human helplessness and divine omnipotence. His eloquence reduced Jonathan Edwards to tears and even caused the skeptical and thrifty Benjamin Franklin to empty his pockets into the collection plate. During these roaring revival meetings, countless sinners professed conversion, and hundreds of the "saved" groaned, shrieked, or rolled in the snow from religious excitation. Whitefield soon inspired

American imitators. Taking up his electrifying new style of preaching, they heaped abuse on sinners and shook enormous audiences with emotional appeals. One preacher cackled hideously in the face of hapless wrongdoers. Another, naked to the waist, leaped frantically about in the light of flickering torches.

Orthodox clergymen, known as "old lights," were deeply skeptical of the emotionalism and the theatrical antics of the revivalists. "New light" ministers, on the other hand, defended the

Awakening for its role in revitalizing American religion. Congregationalists and Presbyterians split over this issue, and many of the believers in religious conversion went over to the Baptists and other sects more prepared to make room for emotion in religion. The Awakening left many lasting effects. [1] Its emphasis on direct, emotive spirituality seriously undermined the older clergy, whose authority had derived from their education and erudition. [2] The schisms it set off in many denominations greatly increased the numbers and the competitiveness of American churches. [3] It encouraged a fresh wave of missionary work among the Indians and even among black slaves, many of whom also attended the mass open-air revivals. [4] It led to the founding of "new light" centers of higher learning such as Princeton, Brown, Rutgers, and Dartmouth. [5] Perhaps most significant, the Great Awakening was the first spontaneous mass movement of the American people. It tended to break down sectional boundaries as well as denominational lines and contributed to the growing sense that Americans had of themselves as a single people, united by a common history and shared experiences.

“I proceed now to the last thing that was proposed to be considered, relating to the success of Christ's redemption during this space, viz., what the state of things is now in the world with regard to the church of Christ, and the success of Christ's purchase.

[1.] The power and influence of the Pope is much diminished. Although, since the former times of the Reformation, he has gained ground In extent of dominion; yet he has lost in degree of influence.

. . .

[2.] There Is far less persecution now than there was in the first times of the Reformation. . . . it is now in no measure as it was heretofore. There does not seem to be the same spirit of persecution prevailing. . . . The humor now is, to despise and laugh at all religion; and there seems to be a spirit of indifferency about it.

[3.] There is a great increase of learning. In the dark times of Popery before the Reformation, learning was so far decayed, that the world seemed to be overrun with barbarous ignorance. . . . the increase of learning in itself is a thing to be rejoiced in, because it is a good. . . . And . . . . God in his providence has of late given the world the art of printing, and such a great increase of learning, to prepare for what he designs to accomplish for his church in the approaching days of its prosperity.

Reason shows that it is fit and requisite, that the intelligent and rational beings of the world should know something of God's scheme and design in his works. . . ." Source: Jonathan Edwards.

A History of the Work of Redemption, works edited by E. Hickman, 10th ed.. 2 vols., (London,

1865), vol.1, pp.470-72,480-81, 492-93, 510-13.

A Revival of Religion

For these and other reasons, we, whose names are hereunto annexed, pastors of churches in

New England, met together in Boston, July 7, 1743, think it our indispensable duty, (without judging or censuring such of our brethren as cannot at present see things in the same light with us,) in this open and conjunct manner to declare, to the glory of sovereign grace, our full persuasion, either from what we have seen ourselves, or received upon credible testimony, that there has been a happy and remarkable revival of religion in many parts of this land, through an uncommon divine influence; after a long time of great decay and deadness. . . .

. . . . Persons have been awakened to a solemn concern about salvation, and have been thought to have passed out of a state of nature into a state of grace. . . . So that, as far as we are able to form a judgment, the face of religion is lately changed much for the better in many of our towns and congregations."

Jonathan Edwards was upset by the "extraordinary dullness in religion" he observed around him. During the first part of the eighteenth century, as the population of the colonies increased and

Americans developed a thriving trade with other parts of the world, they became increasingly worldly in their outlook. It wasn't that they abandoned religion; what they abandoned was the stern, harsh religion that Edwards considered essential to salvation. Edwards, like John Winthrop, was a devout Puritan. He believed human beings were incorrigible sinners, filled with greed, pride, and lust, and that a just God had condemned them to eternal damnation for their transgressions. But

God was merciful as well as just. Because Jesus had atoned for man's sins by dying on the cross,

God agreed to shed his grace on some men and women and elect them for salvation. The individual who was chosen for salvation experienced God's grace while being converted. For Edwards the conversion experience was the greatest event in a person's life. After conversion, the individual dedicated himself to the glory of God and possessed a new strength to resist temptation.

In his sermons, Edwards, pastor of the Congregational church in Northampton,

Massachusetts, tried to impress on people the awful fate that awaited them unless they acknowledged their sinfulness and threw themselves upon the mercy of God. During the last part of

1 734 Edwards delivered a series of sermons that moved his congregation deeply. In them he gave such vivid descriptions of human depravity and the torments awaiting the unredeemed in the next world that people in the congregation wept, groaned, and begged for mercy. Edward's sermons produced scores of conversions. During the winter and spring over three hundred people were converted and admitted to full membership in the church. "This town," wrote Edwards joyfully,

"never was so full of Love, nor so full of Joy, nor so full of distress as it has lately been." The

Ûreligious revival that Edwards led in Northampton was only one of many revivals sweeping

America at this time in New England, in the Middle Colonies, and in the South. The Great

Awakening, as the revivalist movement was called, affected the Presbyterians as well as the

Congregational crisis, and also swept through other denominations, keeping the churches in turmoil from about 1734 to 1756. The Great Awakening did produce a renewed interest in religion, but not always in Edwards's austere Puritanism. Edwards led revivals only in New England. George

Whitefield, an English associate of John Wesley, the founder of Methodism, came to America, toured the colonies, and led revivals wherever he went. He helped make the Great Awakening an inter colonial movement. It was the first movement in which all the colonies participated before the

American Revolution.

Edwards, who was born in East Windsor, Connecticut, in 1703, was a precocious lad. He wrote a treatise on spiders at age twelve and entered Yale College at age thirteen. The son of a

Congregational minister, he experienced conversion as a young man, dedicated his life to the church, and pursued theological studies at Yale after graduation. In 1726 he became associate pastor of the Congregational church in Northampton, and in 1729 he was appointed pastor. For twenty-one years he labored hard in Northampton, studying, writing, and preaching; he also launched his ambitious plan for publishing treatises on all of the great Puritan doctrines. He wrote, too, a psychological analysis of the conversion experience, based on his study of the revivals that took place in Northampton and elsewhere. He delivered his famous sermon, "Sinners in the

Hands of an Angry God" in Enfield, Connecticut, in 1741. In 1750 he took his family to

Stockbridge, Massachusetts. There he spent the rest of his life, preaching and serving as missionary to the Native Americans. In 1758 he was appointed president of the College of New Jersey

(Princeton), but he died of smallpox before beginning his duties there.

Questions to Consider. Edwards delivered his sermons in a quiet, though impassioned, tone of voice and looked at the back wall of the church, not the congregation, while preaching. How, then, was he able, in a sermon like "Sinners in the Hands of an Angry God," to arouse the rapt attention of the people? In what ways did he set forth the sovereignty of God, a prime doctrine of the Puritans? Do you think there is any inconsistency in his belief that only a few people (the elect) are saved and his insistence that everybody strive for salvation? In what ways might the

Great Awakening have fostered anti-establishment, anti-imperial attitudes among the American colonists?

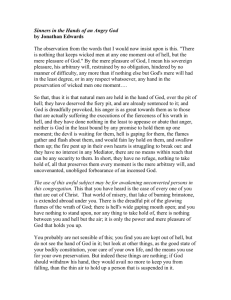

Deuteronomy 32:35. Their foot shall slide in due time.

In this verse is threatened the vengeance of God on the wicked unbelieving Israelites, that were God's visible people, and lived under means of grace; and that notwithstanding all God's wonderful works that he had wrought towards that people, yet remained, as is expressed verse 28, void of counsel, having no understanding in them; and that, under all the cultivations of heaven, brought forth bitter and poisonous fruit; as in the two verses next preceding the text.

The expression that I have chosen for my text, their foot shall slide in due time, seems to imply the following things relating to the punishment and destruction that these wicked Israelites were exposed to:

1. That they were always exposed to destruction; as one that stands or walks in slippery places is always exposed to fall. This is implied in the manner of their destruction's coming upon them, being represented by their foot's sliding. The same is expressed, Psalm 73:18: ''Surely thou didst set them in slippery places; thou castedst them down into destruction.''

2. It implies, that they were always exposed to sudden, unexpected destruction. As he that walks in slippery places is every moment liable to fall, he cannot foresee one moment whether he shall stand or fall the next; and when he does fall, he falls at once, without warning, which is also expressed in that Psalm 73:18, 19: ''Surely thou didst set them in slippery places; thou castedst them down into destruction: how are they brought into desolation as in a moment.''

3. Another thing implied is, that they are liable to fall of themselves, without being thrown down by the hand of another; as he that stands or walks on slippery ground needs nothing but his own weight to throw him down.

4. That the reason why they are not fallen already, and do not fall now, is only that God's appointed time is not come. For it is said that when that due time, or appointed time comes, their feet shall slide. Then they shall be left to fall, as they are inclined by their own weight. God will not hold them up in these slippery places any longer, but will let them go; and then, at that very instant, they shall fall into destruction; as he that stands in such slippery declining ground on the edge of a pit that he cannot stand alone, when he is let go he immediately falls and is lost.

The observation from the words that I would now insist upon is this. There is nothing that keeps wicked men at any one moment out of hell, but the mere pleasure of God. By the mere pleasure of God, I mean his sovereign pleasure, his arbitrary will, restrained by no obligation, hindered by no manner of difficulty, any more than if nothing else but God's mere will had in the least degree or in any respect whatsoever, any hand in the preservation of wicked men one moment.

The truth of this observation may appear by the following considerations:

1. There is no want of power in God to cast wicked men into hell at any moment. Men's hands cannot be strong when God rises up: the strongest have no power to resist him, nor can any deliver out of his hands. He is not only able to cast wicked men into hell, but he can most easily do it.

Sometimes an earthly prince meets with a great deal of difficulty to subdue a rebel, that has found means to fortify himself, and has made himself strong by the number of his followers. But it is not so with God. There is no fortress that is any defense against the power of God. Though hand join in hand, and vast multitudes of God's enemies combine and associate themselves, they are easily broken in pieces: they are as great heaps of light chaff before the whirlwind; or large quantities of dry stubble before devouring flames. We find it easy to tread on and crush a worm that we see crawling on the earth; so it is easy for us to cut or singe a slender thread that any thing hangs by; thus easy it is for God, when he pleases, to cast his enemies down to hell. What are we, that we should think to stand before him, at whose rebuke the earth trembles, and before whom the rocks are thrown down!

2. They deserve to be cast into hell; so that divine justice never stands in the way, it makes no objection against God's using his power at any moment to destroy them. Yea, on the contrary, justice calls aloud for an infinite punishment of their sins. Divine justice says of the tree that brings forth such grapes of Sodom, ''Cut it down, why cumbereth it the ground?'' Luke 13:7. The sword of divine justice is every moment brandished over their heads and it is nothing but the hand of arbitrary mercy, and God's mere will, that holds it back.

3. They are already under a sentence of condemnation to hell. They do not only justly deserve to be cast down thither, but the sentence of the law of God, that eternal and immutable rule of righteousness that God has fixed between him and mankind, is gone out against them; and stands

against them; so that they are bound over already to hell: John 3:18, ''He that believeth not is condemned already.'' So that every unconverted man properly belongs to hell; that is his place; from thence he is: John 8:23, ''Ye are from beneath'': and thither he is bound; it is the place that justice, and God's word, and the sentence of his unchangeable law, assign to him.

4. They are now the objects of that very same anger and wrath of God, that is expressed in the torments of hell: and the reason why they do not go down to hell at each moment, is not because of

God, in whose power they are, is not then very angry with them; as angry, as he is with many of those miserable creatures that he is now tormenting in hell, and do there feel and bear the fierceness of his wrath. Yea, God is a great deal more angry with great numbers that are now on earth; yea, doubtless, with many that are now in this congregation, that, it may be, are at ease and quiet, than he is with many of those that are now in the flames of hell. So that it is not because God is unmindful of their wickedness, and does not resent it, that he does not let loose his hand and cut them off. God is not altogether such a one as themselves, though they may imagine him to be so.

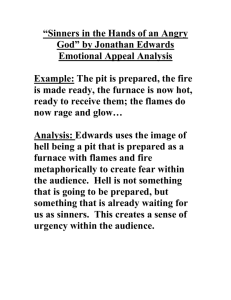

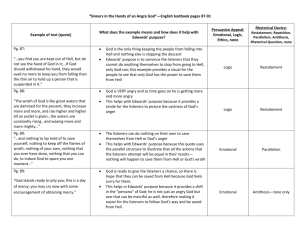

The wrath of God burns against them; their damnation does not slumber; the pit is prepared; the fire is made ready; the furnace is now hot; ready to receive them; the flames do now rage and glow. The glittering sword is whet, and held over them, and the pit hath opened her mouth under them.

5. The devil stands ready to fall upon them, and seize them as his own, at what moment God shall permit him. They belong to him; and he has their soul in his possession, and under his dominion.

The Scripture represents them as his goods, Luke 11:21. The devils watch them, like greedy hungry lions that see their prey, and except to have it, but are for the present kept back; if God should withdraw his hand by which they are restrained, they would in one moment fly upon their poor souls. The old serpent is gaping for them; hell opens its mouth wide to receive them; and if God should permit it, they would be hastily swallowed up and lost.

6. There are in the souls of wicked men those hellish principles reigning, that would presently kindle and flame out into hell-fire, if it were not for God's restraints. There is laid in the very nature of carnal men, a foundation for the torments of hell: there are those corrupt principles, in reigning power in them, and in full possession of them, that are the beginnings of hell-fire. These principles are active and powerful, exceeding violent in their nature, and if it were not for the restraining hand of God upon them, they would soon break out, they would flame out after the same manner as the same corruptions, the same enmity lies in the hearts of damned souls, and would beget the same torments in them as they do in them. The souls of the wicked are in Scripture compared to the troubled sea, Isaiah 57:20. For the present God restrains their wickedness by his mighty power, as he does the raging waves of the troubled sea, saying, ''Hitherto shalt thou come, and no further''; but if God should withdraw that restraining power, it would soon carry all before it. Sin is the ruin and misery of the soul; it is destructive in its nature; and if God should leave it without restraint, there would need nothing else to make the soul perfectly miserable. The corruption of the heart of man is a thing that is immoderate and boundless in its fury; and while wicked men live here, it is like fire pent up by God's restraints, whereas if it were let loose, it would set on fire the course of nature; and as the heart is now a sink of sin, so, if sin was not restrained; it would immediately turn the soul into a fiery oven, or a furnace of fire and brimstone.

7. It is no security to wicked men for one moment, that there are no visible means of death at hand.

It is no security to a natural man, that he is now in health, and that he does not see which way he should now immediately go out of the world by any accident, and that there is no visible danger in any respect in his circumstances. The manifold and continual experience of the world in all ages, shows that this is no evidence that a man is not on the very brink of eternity, and that the ne §xt step will not be into another world. The unseen, unthought of ways and means of

persons going suddenly out of the world are innumerable and inconceivable. Unconverted men walk over the pit of hell on rotten covering, and there are innumerable places in this covering so weak that they will not bear their weight, and these places are not seen. The arrows of death fly unseen at noonday; the sharpest sight cannot discern them. God has so many different, unsearchable ways of taking wicked men out of the world and sending them to hell, that the is nothing to make it appear, that God had need to be at the expense of a miracle, or go out of the ordinary course of his providence, to destroy any wicked man, at any moment. All the means that there are of sinners going out of the world, are so in God's hands, and so absolutely subject to his power and determination, that it does not depend at all less on the mere will of God, whether sinners shall at any moment go to hell, than if means were never made use of, or at all concerned in the case.

8. Natural men's prudence and care to preserve their own lives, or the care of others to preserve them, do not secure them a moment. This, divine providence and universal experience do also bear testimony to. There is this clear evidence that men's own wisdom is no security to them from death; that if it were otherwise we should see some difference between the wise and politic men of the world, and others, with regard to their liableness to early and unexpected death; but how is it in fact? Eccles. 2:16, ''How dieth the wise man? As the fool.''

9. All wicked men's pains and contrivance they use to escape hell, while they continue to reject

Christ, and so remain wicked men, do not secure them from hell one moment. Almost every natural man that hears of hell, flatters himself that he shall escape it; he depends upon himself for his own security, he flatters himself in what he has done, in what he is now doing, or what he intends to do; every one lays out matters in his own mind how he shall avoid damnation, and flatters himself that he contrives well for himself, and that his schemes will not fail. They hear indeed that there are but few saved, and that the bigger part of men that have died heretofore are gone to hell; but each one imagines that he lays out matters better for his own escape than others have done: he does not intend to come to that place of torment; he says within himself, that he intends to take care that shall be effectual, and to order matters so for himself as not to fail.

But the foolish children of men do miserably delude themselves in their own schemes, and in their confidence in their own strength and wisdom, they trust to nothing but a shadow. The bigger part of those that heretofore have lived under the same means of grace, and are now dead, are undoubtedly gone to hell; and it was not because they were not as wise as those that are now alive, it was not because they did not lay out matters as well for themselves to secure their own escape. If it were so that we could come to speak with them, and could inquire of them, one by one, whether they expected, when alive, and when they used to hear about hell, ever to be subjects of that misery, we, doubtless, should hear one and another reply, ''No, I never intended to come here: I had laid out matters otherwise in my mind; I thought I should contrive well for myself: I thought my scheme good. I intended to take effectual care; but it came upon me unexpectedly; I did not look for it at that time, and in that manner; it came as a thief: death outwitted me: God's wrath was too quick for me: O my cursed foolishness! I was flattering myself, and pleasing myself with vain dreams of what I would do hereafter; and when I was saying peace and safety, then sudden destruction came upon me.''

10. God has laid himself under no obligation, by any promise, to keep any natural man out of hell one moment: God certainly has made no promises either of eternal life, or of any deliverance or preservation from eternal death, but what are contained in the covenant of grace, the promises that are given in Christ, in whom all the promises are yea and amen. But surely they have no interest in the promises of the covenant of grace that are not the children of the covenant, and that do not

believe in any of the promises of the covenant, and have no interest in the Mediator of the covenant.

So that, whatever some have imagined and pretended about promises made to natural men's earnest seeking and knocking, it is plain and manifest, that whatever pains a natural man takes in religion, whatever prayers he makes, that he believes in Christ, God is under no manner of obligation to keep him a moment from eternal destruction.

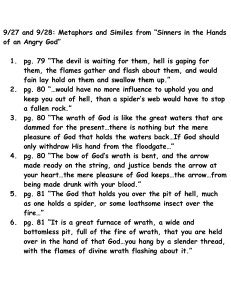

So that thus it is, that natural men are held in the hand of God over the pit of hell; they have deserved the fiery pit, and are already sentenced to it; and God is dreadfully provoked, his anger is as great towards them as to those that are actually suffering the executions of the fierceness of his wrath in hell, and they have done nothing in the least, to appease or abate that anger, neither is God in the least bound by any promise to hold them up one moment; the devil is waiting for them, hell is gaping for them, the flames gather and flash about them, and would fain lay hold on them and swallow them up; the fire pent up in their own hearts is struggling to break out; and they have no interest in any Mediator, there are no means within reach that can be any security to them. In short, they have no refuge, nothing to take hold of; all that preserves them every moment is the mere arbitrary will, and uncovenanted, unobliged forbearance of an incensed God.

Application

The use may be of awakening to unconverted persons in this congregation. This that you have heard is the case of every one of you that are out of Christ. That world of misery, that lake of burning brimstone, is extended abroad under you. There is the dreadful pit of the glowing flames of the wrath of God; there is hell's wide gaping mouth open; and you have nothing to stand upon, nor any thing to take hold of. There is nothing between you and hell but the air; it is only the power and mere pleasure of God that holds you up. You probably are not sensible of this; you find you are kept out of hell, but do not see the hand of God in it; but look at other things, as the good state of your bodily constitution, your care of your own life, and the means you use for your own preservation. But indeed these things are nothing; if God should withdraw his hand, they would avail no more to keep you from falling, than the thin air to hold up a person that is suspended in it.

Your wickedness makes you as it were heavy as lead, and to tend downwards with great weight and pressure towards hell; and if God should let you go, you would immediately sink Sand swiftly descend and plunge into the bottomless gulf, and your healthy constitution, and your own care and prudence, and best contrivance, and all your righteousness, would have no more influence to uphold you and keep you out of hell, than a spider's web would have to stop a falling rock. Were it not that so is the sovereign pleasure of God, the earth would not bear you one moment; for you are a burden to it; the creation groans with you; the creature is made subject to the bondage of your corruption, not willingly; the sun does not willingly shine upon you to give you light to serve sin and Satan; the earth does not willingly yield her increase to satisfy your lusts; nor is it willingly a stage for your wickedness to be acted upon; the air does not willingly serve you for breath to maintain the flame of life in your vitals, while you spend your life in the service of God's enemies.

God's creatures are good, and were made for men to serve God with, and do not willingly subserve to any other purpose, and groan when they are abused to purposes so directly contrary to their nature and end. And the world would spew you out, were it not for the sovereign hand of him who hath subjected it in hope. There are the black clouds of God's wrath now hanging directly over your heads, full of the dreadful storm, and big with thunder; and were it not for the restraining hand of

God, it would immediately burst forth upon you. The sovereign pleasure of God, for the present, stays his rough wind; otherwise it would come with fury, and your destruction would come like a whirlwind, and you would be like the chaff of the summer threshing floor.

The wrath of God is like great waters that are damned for the present; they increase more and more, and rise higher and higher, till an outlet is given; and the longer the stream is stopped, the more rapid and mighty is its course, when once it is let loose. It is true, that judgment against your evil work has not been executed hitherto; the floods of God's vengeance have been withheld; but your guilt in the mean time is constantly increasing, and you are every day treasuring up more wrath; the waters are continually rising, and waxing more and more mighty; and there is nothing but the mere pleasure of God, that holds the waters back, that are unwilling to be stopped, and press hard to go forward. If God should only withdraw his hand from the floodgate, it would immediately fly open, and the fiery floods of the fierceness and wrath of God, would rush forth with inconceivable fury, and would come upon you with omnipotent power; and if your strength were ten thousand times greater than it is, yea, ten thousand times greater than the strength of the stoutest, sturdiest devil in hell, it would be nothing to withstand or endure it.

The bow of God's wrath is bent, and the arrow made ready on the string, and justice bends the arrow at your heart, and strains the bow, and it is nothing but the mere pleasure of God, and that of an angry God, without any promise or obligation at all, that keeps the arrow one moment from being made drunk with your blood.

Thus are all you that never passed under a great change of heart, by the mighty power of the

Spirit of God upon your souls; all that were never born again, and made new creatures, and raised from being dead in sin, to a state of new, and before altogether unexperienced light and life

(however you may have reformed your life in many things, and may have had religious affections and may keep up a form of religion in your families and closets, and in the houses of God, and may be strict in it) you are thus in the hands of an angry God; it is nothing but his mere pleasure that keeps you from being this moment swallowed up in everlasting destruction.

However unconvinced you may now be of the truth of what you hear, by and by you will be fully convinced of it. Those that are gone from being in the like circumstances with you, see that it was so with them; for destruction came suddenly upon most of them; when they expected nothing of it, and while they were saying, Peace and safety: now they see, that those things that they depended on for peace and safety were nothing but thin air and empty shadows.

The God that holds you over the pit of hell, much as one holds a spider, or some loathsome insect, over the fire, abhors you, and is dreadfully provoked; his wrath towards you burns like fire; he looks upon you as worthy of nothing else, but to be cast into the fire; he is of purer eyes than to bear to have you in his sight; you are ten thousand times so abominable in his eyes, as the most hateful and venomous serpent is in ours. You have offended him infinitely more than ever a stubborn rebel did his prince: and yet it is nothing but his hand that holds you from falling into the fire every moment: it is ascribed to nothing else, that you did not go to hell the last night; that you were suffered to awake again in this world, after you closed your eyes to sleep; and there is no other reason to be given, why you have not dropped into hell since you arose in the morning, but that God's hand has held you up: there is no other reason to be given why you have not gone to hell, since you have sat here in the house of God, provoking his pure eyes by your sinful wicked manner of attending his solemn worship: yea, there is nothing else that is to be given as a reason why you do not this very moment drop down into hell.

O sinner! consider the fearful danger you are in: it is a great furnace of wrath, a wide and bottomless pit, full of the fire of wrath, that you are held over in the hand of that God, whose wrath is provoked and incensed as much against you, as against many of the damned in hell: you hang by a slender thread, with the flames of divine wrath flashing about it, and ready every moment to single it, and burn it asunder; and you have no interest in any Mediator, and nothing to lay hold of

to save yourself, nothing to keep off the flames of wrath, nothing of your own, nothing that you ever have done, nothing that you can do, to induce God to spare you one moment.

And consider here more particularly several things concerning that wrath that you are in such danger of:

1. Whose wrath it is. It is the wrath of the infinite God. If it were only the wrath of man, though it were of the most potent prince, it would be comparatively little to be regarded. The wrath of kings is very much dreaded, especially of absolute monarchs, that have the possessions and lives of their subjects wholly in their power; to be disposed of at their mere will. Prov. 20:2, ''The fear of a king is as the roaring of a lion: who so provoketh him to anger, sinneth against his own soul.'' The subject that very much enrages an arbitrary prince, is liable to suffer the most extreme torments that human art can invent, or human power can inflict. But the greatest earthly potentates, in their greatest majesty and strength, and when clothed in their greatest terrors, are but feeble, despicable worms of the dust, in comparison of the great and almighty Creator and King of heaven and earth: it is but little that they can do, when most enraged, and when they have exerted the utmost of their fury. All the kings of the earth before God, are as grasshoppers; they are nothing, and less than nothing: both their love and their hatred is to be despised. The wrath of the great King of kings, is as much more terrible than theirs, as his majesty is greater. Luke 12:4, 5, ''And I say unto you, my friends, be not afraid of them that kill the body, and after that have no more that they can do. But I will forewarn you whom you shall fear: fear him, which after he hath killed, hath power to cast into hell; yea, I say unto you, fear him.''

2. It is the fierceness of his wrath that you are exposed to. We often read of the fury of God; as in

Isaiah 59:18: ''According to their deeds, accordingly he will repay fury to his adversaries.'' So

Isaiah 66:15, ''For behold, the Lord will come with fire and with his chariots like a whirlwind, to render his anger with fury, and his rebuke with flames of fire.'' And so in many other places. So we read of God's fierceness, Rev. 19:15. There we read of ''the wine-press of the fierceness and wrath of Almighty God.'' The words are exceedingly terrible: if it had only been said, ''the wrath of God,'' the words would have implied that which is infinitely dreadful: but it is not only said so, but ''the fierceness and wrath of God'': the fury of God! the fierceness of Jehovah! Oh how dreadful must that be! Who can utter or conceive what such expressions carry in them! But it is not only said so, but ''the fierceness and wrath of Almighty God.'' As though there would be a very great manifestation of his almighty power in what the fierceness of his wrath should inflict, as though omnipotence should be as it were enraged, and exerted, as men are wont to exert their strength in the fierceness of their wrath. Oh! then, what will be the consequence! What will become of the poor worm that shall suffer it! Whose hands can be strong! And whose heart endure! To what a dreadful, inexpressible, inconceivable depth of misery must the poor creature be sunk who shall be the subject of this!

Î Consider this, you that are here present, that yet remain in an unregenerate state. That God will execute the fierceness of his anger, implies, that he will inflict wrath without any pity: when

God beholds the ineffable extremity of your case, and sees your torment so vastly disproportioned to your strength, and sees how your poor soul is crushed, and sinks down, as it were, into an infinite gloom; he will have no compassion upon you, he will not forbear the executions of his wrath, or in the least lighten his hand; there shall be no moderation or mercy, nor will God then at all stay his rough wind; he will have no regard to your welfare, nor be at all careful lest you should suffer too much in any other sense, than only that you should not suffer beyond what strict justice requires: nothing shall be withheld, because it is so hard for you to bear. Ezek. 8:18, ''Therefore will I also deal in fury; mine eye shall not spare, neither will I have pity; and though they cry in mine ears

with a loud voice, yet will I not hear them.'' Now God stands ready to pity you; this is a day of mercy; you may cry now with some encouragement of obtaining mercy: but when once the day of mercy is past, your most lamentable and dolorous cries and shrieks will be in vain; you will be wholly lost and thrown away of God, as to any regard to your welfare; God will have no other use to put you to, but only to suffer misery; you shall be continued in being to no other end; for you will be a vessel of wrath fitted to destruction; and there will be no other use of this vessel, but only to be filled full of wrath: God will be so far from pitying you when you cry to him, that it is said he will only ''laugh and mock,'' Prov. 1:25, 26, etc.

How awful are those words, Isaiah 63:3, which are the words of the great God: ''I will tread them in mine anger, and trample them in my fury, and their blood shall be sprinkled upon my garments, and I will stain all my raiment.'' It is perhaps impossible to conceive of words that carry in them greater manifestations of these three things, viz., contempt and hatred, and fierceness of indignation. If you cry to God to pity you, he will be so far from pitying you in your doleful case, or showing you the least regard or favor, that instead of that he will only tread you under foot: and though he will know that you cannot bear the weight of omnipotence treading upon you, yet he will not regard that, but he will crush you under his feet without mercy; he will crush out your blood, and make if fly, and it shall be sprinkled on his garments, so as to stain all his raiment. He will not only hate you, but he will have you in the utmost contempt; no place shall be thought fit for you but under his feet, to be trodden down as the mine in the streets.

3. The misery you are exposed to is that which God will inflict to that end, that he might show what that wrath of Jehovah is. God hath had it on his heart to show to angels and men, both how excellent his love is and also how terrible his wrath is. Sometimes earthly kings have a mind to show how terrible their wrath is, by the extreme punishments they would execute on those that provoke them. Nebuchadnezzar, that mighty and haughty monarch of the Chaldean empire, was willing to show his wrath when enraged with Shadrach, Meshech, and Abednego; and accordingly gave order that the burning fiery furnace should be heated seven times hotter than it was before; doubtless it was raised to the utmost degree of fierceness that human art could raise it; but the great

God is also willing to show his wrath, and magnify his awful Majesty and mighty power in the extreme sufferings of his enemies. Rom. 9:22, ''What if God, willing to show his wrath, and to make his power known endured with much long-suffering, the vessels of wrath fitted to destruction?'' And seeing this is his design and what he has determined, to show how terrible the unmixed, unrestrained wrath, the fury, and fierceness of Jehovah is, he will do it to effect. There will be something accomplished and brought to pass that will be dreaded with a witness. When the great and angry God hath risen up and executed his awful vengeance on the poor sinner, and the wretch is actually suffering the infinite weight and power of his indignation, then will God call upon the whole universe to behold that awful majesty and mighty power that is to be seen in Isa.

33:12, 13, 14, ''And the people shall be as the burning of lime, as thorns cut up shall they be burnt in the fire. Hear, ye that are afar off, what I have done; and ye that are near acknowledge my might.

The sinners in Zion are afraid; fearfulness hath surprised the hypocrites,'' etc.

Thus it will be with you that are in an unconverted state, if you continue in it; the infinite might, and majesty, and terribleness, of the omnipotent God shall be magnified upon you in the ineffable strength of your torments: you shall be tormented in the presence of the holy angels, and in the presence of the Lamb; and when you shall be in this state of suffering, the glorious inhabitants of heaven shall go forth and look on the awful spectacle, that they may see what the wrath and fierceness of the Almighty is; and when they have seen it, they will fall down and adore that great power and majesty. Isa. 66:23, 24, ''And it shall come to pass, that from one moon to

another, and from one Sabbath to another, shall all flesh come to worship before me, saith the Lord.

And they shall go forth and look upon the carcasses of the men that have transgressed against me; for their worm shall not die, neither shall their fire be quenched, and they shall be abhorring unto all flesh.''

4. It is everlasting wrath. It would be dreadful to suffer this fierceness and wrath of Almighty God one moment; but you must suffer it to all eternity: there will be no end to this exquisite, horrible misery: when you look forward, you shall see a long forever, a boundless duration before you, which will swallow up your thoughts, and amaze your soul; and you will absolutely despair of ever having any deliverance, any end, any mitigation, any rest at all; you will know certainly that you must wear out long ages, millions of millions of ages, in wrestling and conflicting with this

Almighty merciless vengeance; and then when you have so done, when so many ages have actually been spent by you in this manner, you will know that all is but a point to what remains. So that your punishment will indeed be infinite. Oh, who can express what the state of a soul in such circumstances is! All that we can possibly say about it, gives but a very feeble, faint representation of it; it is inexpressible and inconceivable: for ''who knows the power of God's anger?''

How dreadful is the state of those that are daily and hourly in danger of this great wrath and infinite misery! But this is the dismal case of every soul in this congregation that has not been born again, however moral and strict, sober and religious, they may otherwise be. Oh that you would consider it, whether you be young or old! There is reason to think, that there are many in this congregation now hearing this discourse, that will actually be the subjects of this very misery to all eternity. We know not who they are, or in what seats they sit, or what thoughts they now have. It may be they are now at ease, and hear all these things without much disturbance, and are now flattering themselves that they are not the persons; promising themselves that they shall escape. If we knew that there was one person, and but one, in the whole congregation, that was to be the subject of this misery, what an awful thing it would be to think of! If we knew who it was, what an awful sight would it be to see such a person! How might all the rest of the congregation lift up a lamentable and bitter cry over him! But alas! Instead of one, how many is it likely will remember this discourse in hell! And it would be a wonder, if some that are now present should not be in hell in a very short time, before this year is out. And it would be no wonder if some persons, that now sit here in some seats of this meeting-house in health, and quiet and secure, should be there before tomorrow morning. Jonathan Edwards's ''Sinners in the Hands of an Angry God'' Sermon, 1741.

Living Documents in American History, p. 125-139.

The Great Awakening and Church Membership

The Great Awakening of 1739-1745 temporarily altered the pattern of church adherence described above. Indeed this foremost revival, as well as periodic and more localized quickenings, can be defined in part not only by surging church admissions but by heavier concentrations than usual from two constituencies: men and young people. A typical report came from the Reverend

Peter Thacher of Middleborough, Massachusetts: "the Grace of God has surprisingly seized and subdued the hardiest men, and more Males have been added here than the tenderer sex." In addition, many youths were "erring and wringing their hands, and bewailing their Frolicking and

Dancing." At Woodbury, Connecticut, between 1740 and 1742, First Church added fifty-nine male to forty-six female members. The awakened flocked to their minister in Wrentham, Massachusetts,

"especially young People, under Soul Distress." From Natick came word that "Indians and English,

Young and Old, Male and Female" had been called to Christ. In New England those who joined the

churches during the revival were on average six years younger than members affiliating before the

Awakening, a pattern that pertained also in the Middle Colonies. Considering the ministers' perennial concern for the rising generation, this melting of young hearts was especially gratifying.

The addition of larger numbers of men also tended, at least temporarily, to slow the ferninzation of churches.

Women nonetheless continued to be drawn into the churches during the Great Awakening, where they spoke up more confidently than ever before. Boston's anti-revivalist minister Charles

Chauncy, alarmed when "FEMALE EXHORTERS" began to appear, declared that "encouraging

WOMEN, yea, GIRLS to speak in the assemblies for religious worship" was a clear breach of the

Lord's commandment. One Old Light explained the peculiar s êusceptibility of women and youths to the emotionalism of the revival as follows: "The aptness of Children and Women to weep. . . in greater Abundance than grown Persons and Men is a plain proof. . . that their Fluids are more numerous in Proportion to their Solids, and their Nerves are weak."

The revival's emphasis on the spoken rather than the written word, and its concern for reaching out to new constituencies, gave it a broad social base. Blacks and Indians, groups with an oral tradition, frequently attended revival meetings in the North. George Whitefield, finding that

Negroes could be "effectually wrought upon, and in an uncommon manner," developed "a most winning way of addressing them." In New England, blacks and Indians drawn to the Awakening were sometimes brought directly into the body of the church. Plymouth New Lights had among their members at least "a Negro or two who were directed to invite others to come to

Christ," and at Gloucester, where a number of blacks joined the êchurch, there was "a society of Negroes, who in their meetings behave very seriously and decently." When the New Light preacher Eleazer Wheelock visited Taunton, Massachusetts, in 1741, he left "almost all the Negroes in town wounded: three or four converted." And Wheelock's work among the Indians led, of course, to the founding of a school that later became Dartmouth College. David Brainerd gained a number of converts to Christianity among the Indians of New Jersey. James Davenport was responsible for the conversion of Samson Occum, an eighteen-year-old Mohegan from

Connecticut. Occum attended Wheelock's school at Lebanon, Connecticut, for four years, was ordained by the Presbyterian Church in 1759, and carried the message of the revival to many of his brethren in Connecticut and New York. Scattered evidence suggests that the Awakening may have had a more significant and long-range impact on blacks than on any other northern group.

Nor can it be doubted that the revival reached out to servants and laborers among the white population. As Dr. Alexander Hamilton commented with typical astringency during a 1744 trip throughout the North, even "the lower class of people here. . . talk. . . about justification, sanctification, adoption, regeneration, repentance, free grace, reprobation, original sin, and a thousand other such pritty, chimerical knick knacks as if they had done nothing but studied divinity all their life time." Still, the lowly origins of the awakened can easily be overstated. It is quite possible that the likeliest prospects for conversion came, after all, from the growing and varied ranks of the middle class, people who counted just a bit less than they felt they should in church and town, and for whom the revival opened up new possibilities and uncertaintie, great hopes, great fears, great expectations.

Religious awakening came later to the colonial South, starting in the mid-1740s with

Presbyterian itinerants and reaching full pitch in the 1760 ís and 1770s with the Baptist and

Methodist revivals. How churchgoing was affected by these revivals remains to be explored, though long-standing regional characteristics probably shaped the southerners' response. Men and women may have continued to participate in church life in relatively equal numbers, whereas

young people and Indians, pending new evidence, appear to have been only marginally affected by the revival. Negroes were another matter, however, for all evangelical denominations reported growing numbers of blacks among their adherents. Presbyterian Samuel Davies counted several hundred Negroes in his New Side [evangelical, revivalist] congregations in Virginia. The added dimension that religion gave to black lives is implicit in Davies's comment about the slaves' delight in psalmody: "Whenever they could get an hour's leisure from their masters, [they would hurry away to my house. . . to gratify their peculiar taste for Psalmody. Sundry of them have lodged all night in my kitchen; and, sometimes, when I have awaked about two or three a-clock in the morning, a torrent of sacred harmony poured into my chamber, and carried my mind away to

Heaven. In this seraphic exercise, some of them spend almost the whole night."

To be sure, only a tiny proportion of blacks were active Christians before the Revolution.

Yet great changes were in the making. In religion the implied promise of some small measure of fulfillment, in a life that otherwise had little of it, was considerable, and a foundation was being laid upon which future generations would construct the central institution of Afro-American culture.

The Great Awakening caused a visible warp in the configuration of colonial church adherence. True, for most groups the change was no more than temporary, as pre-Awakening patterns reemerged once the revival subsided. One continuing legacy of the Awakening, however, was that it stimulated a rise in the number of preachers, especially lay preachers, thereby facilitating the extension of religion to the frontier and other under served sections. Individuals who had been beyond the reach of ministers and church, wing more to circumstances than choice, were now brought within the purview of a structured religious community. That this previously isolated constituency tended to have a higher proportion of young people, immigrants, and economically marginal persons than were located in the longer settled towns and cities goes far to explain the popular overtones of the revival. The growth of religious institutions was not dependent, of course, on the Great Awakening or any other revival. Far from reviving a languishing church life, the

Awakening bespoke the vitality and widening reach of an expanding religious culture. . .

The Great Awakening in Connecticut, 1740

Now it pleased God to send Mr. Whitefield into this land; and my hearing of his preaching at Philadelphia, like one of the old apostles, and many thousands flocking to hear him preach the

Gospel, and great numb òers were converted to Christ, I felt the Spirit of God drawing me by conviction; I longed to see and hear him and wished he would come this way. I heard he was come to New York and the Jerseys and great multitudes flocking after him under great concern for their souls which brought on my concern more and more, hoping soon to see him; but next I heard he was at Long Island, then at Boston, and next at Northampton. Then on a sudden, in the morning about S or 9 of the dock there came a messenger and said Mr. Whitefield preached at Hartford and

Wethersfield yesterday and is to preach at Middletown this morning at ten of the dock. I was in my field at work. I dropped my tool that I had in my hand and ran home to my wife, telling her to make ready quickly to go and hear Mr. Whitefield preach at Middletown, then ran to my pasture for my horse with all my might, fearing that I should be too late. Having my horse, I with my wife soon mounted the horse and went forward as fast as I thought the horse could bear; and when my horse got much out of breath, I would get down and put my wife on the saddle and bid her ride as fast as she could and not stop or slack for me except I bade her, and so [would run until I was much out of breath and then mount my horse again, and so I did several times to favour my horse. We improved every moment to get along as if we were fleeing for our lives, all the while fearing we should be

too late to hear the sermon, for we had twelve miles to ride double in little more than an hour and we went round by the upper housen parish. And when we came within about half a mile or a mile of the road that comes down from Hartford, Wethersfield, and Stepney to Middletown, on high land

[saw before me a cloud of fog arising. I first thought it came from the great river, but as came nearer the road I heard a noise of horses' feet coming down the road, and this cloud was a cloud of dust made by the horses' feet. It arose some rods into the air over the tops of hills and trees; and when I came within about 20 rods of the road, I could see men and horses slipping along in the cloud like shadows, and as I drew nearer it seemed like a steady stream of horses and their riders, scarcely a horse more than his length behind another, all of a lather and foam with sweat, their breath rolling out of their nostrils every jump. Every horse seemed to go with all his might to carry his rider to hear news from heaven for the saving of souls. It made me tremble to see the sight, how the world was in a struggle. I found a vacancy between two horses to slip in mine and my wife said

"Law, our clothes will be all spoiled, see how they look," for they were so covered with dust that they looked almost all of a colour, coats, hats, shirts, and horse. We went down in the stream but heard no man speak a word all the way for 3 miles but every one pressing forward in great haste; and when we got to Middletown old meeting house, there was a great multitude, it was said to be 3 or 4,000 of people, assembled together. We dismounted and shook off our dust, and the ministers were then coming to the meeting house. I turned and looked towards the Great River and saw the ferry boats running swift backward and forward bringing over loads of people, and the oars rowed nimble and quick. Everything, men, horses, and boats seemed to be struggling for life. The land and banks over the river looked black with people and horses; all along the 12 miles I saw no man at work in his field, but all seemed to be gone. When I saw Mr. Whitefleld come upon the scaffold, he looked almost angelical; a young, slim, slender youth, before some thousands of people with a bold undaunted countenance. And my hearing how God was with him everywhere as he came along, it solemnized my mind and put me into a trembling fear before he began to preach; for he looked as if he was dothed with authority from the Great God, and a sweet solemn solemnity sat upon his brow, and my hearing him preach gave me a heart wound. By God's blessing, my old foundation was broken up, and I saw that my righteousness would not save me.

*A Mestee is a person of mixed European and Indian ancestry. SOURCE: Nathan Cole, ms. cited in Leonard W. Labaree, "George Whitefield Comes to Middletown," William and Mary Quarterly, ser. 7 (1950): 5-9.