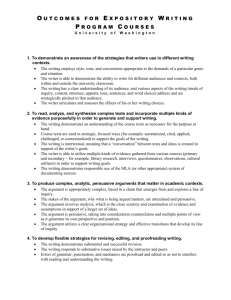

Word Document for Printing

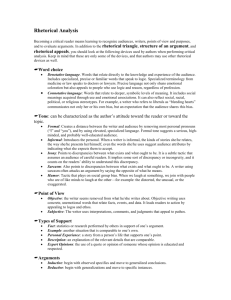

advertisement