The 2008 Debates 1 Running head: THE 2008 TELEVISED

advertisement

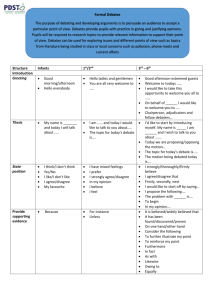

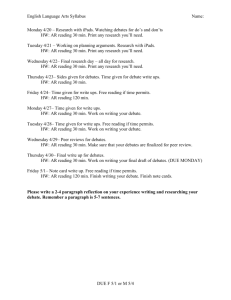

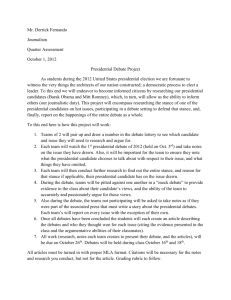

The 2008 Debates Running head: THE 2008 TELEVISED DEBATES: AN ANACHRONISM? The 2008 Televised Debates: What Does It Mean to be ‘Presidential,’ and Are They a Media Anachronism? Michael Dorsher, Jack Kapfer, and Jan Larson University of Wisconsin-Eau Claire David Crowley and Harold Waller McGill University 1 The 2008 Debates 2 Abstract A transnational team of researchers surveyed 69 students at a Canadian university and 332 at a U.S. university after they watched the 2008 presidential debates or learned about them through other media. Inspired by the legend that Nixon bested Kennedy in the 1960 debates among radio listeners but not television viewers, the current study builds on a study of the 2004 debates. It now includes 135 students who participated in an experiment whereby approximately half of them watched one of the 2008 debate telecasts and the other half listened to the debates without video, and all of them completed surveys immediately afterward, before hearing any of the media analysis. The other 266 participants responded to a parallel online survey within a few days of watching one of the debates or learning about it through other media. In an effort to explicate what it means to seem "presidential," all 401 of the study participants rated the debaters on 15 possible characteristics that make a candidate "presidential." The results of the study indicate the 2008 debates had little effect on whom citizens favored for the White House, because there were very few significant differences in the participants' ratings of debaters, whether they watched a debate, listened to it, or learned about it later through the media, regardless of whether they were American or Canadian. We attribute this to media priming and framing of the debates. Factor analysis indicates that to be "presidential" is to seem confident, determined, likable and able to bring about change and consensus. The 2008 Debates 3 The 2008 Televised Debates: What Does It Mean to be ‘Presidential,’ and Are They a Media Anachronism? Researchers of political debates need to undertake more ambitious projects, according to The Racine Group, an ad hoc consortium of 10 U.S. researchers who met in Racine, WI, in 2001 and published their conclusions in 2002. Researchers need to give more consideration, they said, to nonverbal communication, pre-debate priming, and post-debate framing along with the moreapparent verbal, learning, and elections effects of debates. This study is a step in that direction. It builds upon a quasi-experimental study of nonverbal communication in the 2004 U.S. presidential debates (Dorsher, 2006) by adding an international component to a study of the 2008 presidential debates. In addition to replicating the quasi-experimental 2004 study during the 2008 debates, it goes outside the controlled setting and surveys U.S. and Canadian citizens on their reactions to the 2008 debates, whether they watched them on television or not. Finally, the present study seeks to explicate what it takes for a debater to seem “presidential,” which is the one truly independent variable (i.e., other than party affiliation or pre-debate favored candidate) that best predicts the debate “winner,” according to the 2004 study and several others (Dorsher, 2006; Jones, 2005; Lanoue, 1991). Or is it? This study questions whether it’s in-debate events that portend the debate winner for most people so much as it is extra-debate media factors. How much of citizens’ perceptions of the debates is determined by what’s said about the debates-beforehand and afterward--in news stories, campaign ads, online discussions and videos, broadcast talk shows, and satirical televisions shows such as “Saturday Night Live,” “The Daily Show with Jon Stewart,” and “The Colbert Report”? Ultimately, these media messages about the debates might overshadow anything said or done during the debates themselves, sometimes reducing them to mere fodder for the humor mill. The 2008 Debates 4 Literature Review To be sure, no two debates are exactly alike, nor are any campaigns (Patterson, 1980). This was especially true of the 2008 presidential campaign, which featured the first female Republican nominee for vice president, the first female frontrunner for the Democratic presidential nomination, who was overtaken by the first African-American nominee, who became president after holding off the Republican nominee in a series of debates held amidst the worst financial crisis in nearly 80 years. And the 2008 presidential debates accelerated a trend of mediation. It began in 1960 with the first televised debates, resumed in 1976 with the first debate where journalists essentially overturned the verdict, and transformed in 2000 when “Saturday Night Live” eclipsed Sunday morning press shows as the place where nominees redeemed their image. Similarly, no two voters—or non-voting members of the debate audience—are alike in the way debates affect them. But surrounding them all are increasing amounts of media that refer to the presidential debates in an increasing number of ways. Debates History Debate participants, citizens, and experts have debated the value of presidential debates since long before their actual inception. The history of U.S. political debates dates to 1788, when James Madison won a seat in the first Continental Congress after debating James Monroe all across Virginia. But for the nation’s first 175 years, presidential candidates considered it beneath their dignity to engage in face-to-face debates. Incumbents stayed in the White House and acted presidential. Challengers also often left the dirty work of campaigning to their surrogates. One of these was Abraham Lincoln, who campaigned for Whig nominees John C. Fremont in 1836 and Zachary Taylor in 1848. Lincoln’s famous 1858 debates with Stephen Douglas were for a U.S. Senate seat from Illinois; Lincoln did not debate or actively campaign The 2008 Debates 5 when he won the presidency in 1860. It was not until 1948 that presidential candidates debated in a primary, when Republicans Harold Stassen and Tom Dewey squared off in a radio broadcast. In 1956, Democratic primary candidates Estes Kefauver and Adlai Stevenson debated on radio--and TV. But it took until 1960—100 years after Lincoln’s election—for the Republican and Democratic nominees for president to debate, and the telecast of that genteel confrontation between Vice President Richard Nixon and U.S. Sen. John F. Kennedy of Massachusetts changed politics forever. "When it was all over," said Don Hewitt, who directed the initial “Great Debates” telecast in 1960, "a man walked out of this studio the president of the United States. He didn't have to wait till election day" (Schroeder, 2008, p. 8). Nixon, as losers of the first debate often do, recovered and held his own against Kennedy in their three other debates, but he had lost his lead in the polls, and he lost the national election by a mere 112,881 votes. In one of the first examples of post-debate-telecast “spin,” Nixon and his aides claimed that he’d actually had the stronger arguments in the first debate, according to the majority of radio listeners, who were not swayed by Kennedy’s glowing tan and Nixon’s apparent wan. Despite the persistence of that legend in the popular press, academics have found the cited evidence for it unreliable, and in surveys or experiments, they have seldom found a correlation between debaters’ physical features and their audience ratings (Dorsher, 2006; Druckman, 2003; Kraus, 1962). The Cons of Presidential Debates Rather, the criticisms of televised presidential debates have focused on technological effects that allegedly emphasize style over substance. “[P]residential debates are best apprehended as television shows, governed not by the rules of rhetoric or politics but by the demands of their host medium. The values of debates are the values of television: celebrity, The 2008 Debates 6 visuals, conflict, and hype” (Schroeder, 2008, p. 9, italics in the original). Presidential debates, unlike forensic debates, discourage confrontation between the candidates; they extend the “horse race” mentality of campaign polling and encourage candidates to score wins with one liners; and they ignore many of the skills a president needs, such as asking good questions, securing good advice, and acting judiciously (Jones, 2005). Others criticize presidential debates for “gotcha” grandstanding by reporter panelists or moderators (Lanoue and Schrott, 1991), “oversimplification” by candidates (Lemert, 1996), and a lack of specificity (Hart, 1982). They invite sloganeering and a menagerie of topics that leave the audience with an “informational blur,” said Jamieson (1988, p. 119). “The superficial is rewarded; the substantive, spurned." Debaters complain that analysts ignore their policy stances and focus on their gaffes, such as President Ford’s 1976 declaration that the Soviets didn’t dominate Eastern Europe or Vice President Gore’s off-camera sighing in 2000 (Ragazzini, 1985). Debaters also resent the reverseangle shots of them while their opponent speaks and the tendency of frontrunners to play it safe, aiming not to lose debates rather than win them (Jones, 2005). Indeed, the overarching complaint against presidential debates is that seldom do they persuade anyone to change their mind about whom to vote for in November. For all the effort candidates put into them and all the attention the media and audience give them, debates have rarely, if ever, determined who won the presidency. The Pros of Presidential Debates Many researchers insist that presidential debates do have unique benefits. First, they say that debate performances can sway enough votes to determine a close election. In 1960, 44% of those polled said the Nixon-Kennedy debates influenced their vote, while 5% said they based their choice on nothing else (“Debating the debates,” 2008), and Roper pollsters concluded those The 2008 Debates 7 debates altered the voting intentions of four million voters--nearly 40 times the margin of victory for Kennedy (Benoit, 1999). Even if debates do not win elections, they more often might seal them, because good debate performances can reinforce candidates’ support (Lanoue and Schrott, 1991; Leroux, 1992). They can energize formerly tacit supporters into active recruiters and campaign donators, and they can solidify the support of those who were wavering. Other debate benefits for candidates are that they offer free air time and the opportunity to appeal directly to large audiences without having reporters and editors filter their message—at least until after the debate. Most times, voters’ assessment of both candidates rise after a set of presidential debates (Blais and Perrella, 2008; Richardson et al., 2008). In 2008, for example, 46% of a national sample of uncommitted voters said the first debate improved Sen. Obama’s image, and 32% said it had improved Sen. McCain’s image (CBS Poll, 2008). For audience members, the biggest benefit of debates is the rare opportunity to assess presidential candidates for themselves rather than through news stories, campaign ads, or speeches. Watching and listening to candidates respond to moderators—and, occasionally, to each other—is how voters vicariously interview their president. A few voters even got to directly ask their question of the nominees in recent town hall-style debates. In addition to helping citizens decide whom to vote for, debates have other potential benefits for those in the TV audience. They can help citizens learn more about issues in the election and reinforce their faith in democracy (Trent and Friedenberg, 1991). And debates can serve as a check on candidates’ veracity and manipulations in ways that campaign ads and speeches do not, Jamieson (1988) said, adding: “In a world in which sharks and sitcoms lure voters from political substance, a world in which spot ads and news snippets masquerade as significant political fare, a world in The 2008 Debates 8 which most citizens believe that it is better to receive information than to seek it, debates are a blessing” (p. 161). The Canadian Experience Televised debates among candidates for prime minister in Canada and European countries often appear to be more lively and election-changing than U.S. presidential debates. That may be because these debates often feature more than two candidates, and their parties often reflect a greater ideological variety than do U.S. Republicans and Democrats (Lanoue, 1991). The first Canadian leadership debate that appeared to make a difference at the polls was in 1984, when they first had a French debate on one night (July 24) and an English debate the next night, and Brian Mulroney won them both over John Turner, according to 78% of those polled. Even in Montreal, those who said they would vote for the conservatives rose from 15% to 26% after the debate. And in Toronto, where 47% said Mulroney won, support for the Liberals fell from 46% to 25%, while support for the New Democratic Party rose from 10% to 18% (Moniere, 1988). The Conservatives demonstrably benefitted from Mulroney's strong showing, especially in the French debate and especially among francophone voters (Lanoue, 1991). In the 1988 rematch between Mulroney and Turner, along with NDP leader Ed Broadbent, the polls showed Turner won the debates this time. In the election, Mulroney and the Conservatives held on to their majority despite losing 42 seats in Parliament, but Turner’s Liberals widened their lead over the NDP from 10 seats to 40. “Had there been no debates or had John Turner not won the debates, the Liberals and the NDP would have been involved in a close race for second place and it is not even certain that the Liberals would have formed the official opposition. The debates made a big difference, of real political significance” (Blais and Boyer, 1996, p. 161). In a 2008 article, Blais and Perrella pooled survey data surrounding all of The 2008 Debates 9 the Canadian and U.S. televised leadership debates from 1976 to 2004 and reached four conclusions: Debates tend to raise ratings for all candidates involved; that even includes the perceived loser of the debate; incumbents’ ratings rarely suffer after debates; and debates tend to narrow gaps between candidates rather than produce a decisive leader. The ‘Presidential’ Image Even since Sept. 26, 1960, when the first bead of sweat raised on Richard Nixon’s upper lip under the hot studio lights, critics have complained that image trumps substance in televised presidential debates (Lanoue and Schrott, 1991; Jamieson and Birdsell, 1980; Nixon, 1962). But campaign advisers have always acknowledged the importance of image (Martel, 1983). Their job is to carefully construct and maintain the most effective image for their candidate, be it through campaign ads, speeches, or debates. And in presidential debates, they know, the image that researchers have found to be the most influential on voters is to appear “presidential” (Dorsher, 2006; Jones, 2005; Lanoue, 1991). Journalists and voters seem to intuitively understand how a president should look, sound, and act (Lanoue, 1991), but unpacking the components of this “presidential” image is an exercise that researchers have often ignored or failed to accomplish. Leadership, competence, and integrity appear to be three of the characteristics that make a candidate presidential, according to Miller et al. (1986). Honesty, warmth, and caring, Jones (2005) added to the list. “Voters appear to want a human being as president, not a politician,” said Jamieson and Birdsell (1988, p. 140). What is clear is that it’s not always the oldest, most experienced debate candidate who comes off as the most presidential. Analysts and polls declared John F. Kennedy as more presidential than Richard Nixon in 1960, John Kerry as more presidential than George W. Bush in 2004, and Barack Obama as more presidential than John McCain in 2008. Lanoue and Schrott developed the most sophisticated The 2008 Debates 10 model of debate effects (1991, p. 134), with candidate image as its central component. They theorize candidate image as comprising debate content filtered by audience biases and media interpretations. The candidates’ image, in turn, influences how debate watchers evaluate the candidates and the issues—and ultimately how they vote (or decide not to vote). One of the goals of the current study is to use factor analysis to find the combination of characteristics that debate audiences equate most with being “presidential.” Extra-Debate Media Factors For fear of losing his incumbent “presidential” image, President Johnson refused to debate Republican nominee Barry Goldwater during the 1964 campaign, even though President Kennedy, shortly before his Nov. 22, 1963, assassination, had promised Goldwater a crosscountry series of 22 debates, a la Lincoln and Douglas (Lemert, 1996). Nixon refused to debate in 1968, when he resurrected his career and narrowly defeated Hubert Humphrey for the presidency. As the incumbent in 1972, Nixon also refused to debate George McGovern en route to a landslide re-election victory. Nixon had seemed to learn his lesson about the danger of televised debates from his 1960 encounters with Kennedy—until he succumbed to the lucrative temptation to resurrect his presidential image once again by agreeing to a lengthy on-camera interview with British talk show host David Frost. The Broadway show and 2008 movie “Frost/Nixon” depicted the events that led to that coup de grâce. It was not until 16 years after the Nixon-Kennedy debates that the next presidential debates began. Republican Gerald Ford, having gained the presidency not by election but by Nixon’s 1974 resignation amidst the Watergate scandal and having pardoned Nixon to the dismay of much of the nation, decided he had no presidential image to lose by debating Democratic nominee Jimmy Carter, the governor of Georgia. Here begins the history of how the The 2008 Debates 11 news and entertainment media have affected the public’s perception of presidential debates. Researchers have explained these effects through the theory of media framing, a process by which the media’s portrayal of an event significantly influences audience members’ perception of the event, especially if they have little expertise on the issue or few other influences, such as discussions with friends and family (Chong and Druckman, 2007; Sears and Chaffee, 1979; Tuchman, 1978). Immediately after the first 1976 debate, for example, audience surveys said Carter won by a 7-4 margin, but most of the TV analysts and newspaper reporters indicated Ford had won. Nationwide polls reflected that sentiment a few days later, with a 7-4 majority saying Ford won the first debate (Lang and Lang, 1979). The debate reporting effect was even greater after the second Ford-Carter debate. Immediately following that debate, participants in a study by Steeper (1978) rated Ford the winner, by a margin of 44% to 35%, with the rest undecided or calling it a draw—and they recorded high marks for Ford in their electronic ratings during the debate, even when he declared that the Soviet Union did not dominate Eastern Europe. But in just 24 hours, after every major news outlet focused on the naiveté or simple erroneous of that remark, 61% of the respondents in a national survey said Carter had won the second debate, compared to just 9% still declaring Ford the victor—and Ford never recovered in the polls or on election day (Jones, 2005). Similarly, in the second 1988 debate, national survey respondents said Republican George H.W. Bush beat Democrat Michael Dukakis, by a margin of 44% to 30%, but Bush’s winning margin grew to 52% to 8% after four days of the media lambasting Dukakis for the insensitivity of one of his answers during the debate. As Shapiro recounted: “Moderator Bernard Shaw asked Michael Dukakis the Big Question presumably all America wanted answered: ‘If Kitty Dukakis were raped and murdered, would you favor an irrevocable death penalty for the killer?’ Even The 2008 Debates 12 with four years of hindsight, that hypothetical query still chills with its smarmy invasiveness and macabre posturing. Politically, of course, Dukakis' unemotional, uninflected, unyielding answer (‘No, I don't, Bernard’) was in effect his concession speech” (1992, p. 32). Since the 2000 presidential campaign, the effects of framing from newspaper and television journalists have weakened, along with their audience sizes, while the effects have increased from the Internet and TV entertainment shows (Jones, 2005). The trend may have begun in 1968 with Nixon’s “Sock it to me” appearance on “Laugh-In” or in 1992 with Democratic nominee Bill Clinton’s appearance on the Arsenio Hall Show in dark sunglasses, jamming with the band on his saxophone, but it began to rival the debates for attention in 2000, when Vice President Al Gore and Republican nominee George H. Bush separately appeared on late-night TV talk shows and “Saturday Night Live.” SNL skits reinforced or changed the perceptions of many viewers who had watched the 2000, 2004, and 2008 debates—and became the main source of information about them for many who had not (Pfau, 2002; Smith and Voth, 2002). Some Internet blogs became important secondary, if not primary, sources of information about the 2004 and 2008 debates and overall campaigns (Internet’s broader role, 2008). And Barack Obama’s 2008 campaign raised a record-shattering $600 million-plus, primarily through Internet communications with donors whose contributions averaged less than $100 each (Luo, 2008). A national survey at the end of 2007 found that 24% of Americans were using the Internet to learn about the presidential campaigns, including 37% of young adults, ages 18-24. Most were doing so not by accessing candidates’ Web sites but via social networking sites such as Facebook and MySpace (Internet’s broader role, 2008). Also, 41% of adults under age 30 said they used online video sites such as YouTube to watch excerpts of primary election debates and other campaign information, including comedy spoofs. By election day 2008, viewers had The 2008 Debates 13 replayed SNL’s skits on Republican vice presidential nominee Sarah Palin more than 8 million times on YouTube, and they’d watched Palin’s interview with CBS anchor Katie Couric more than 3 million times on YouTube. In addition, 28% of the national survey respondents (39% of those under 30) said they learned about the presidential campaign from comedy shows such as SNL, “The Daily Show with Jon Stewart,” and “The Colbert Report.” Similarly, 28% overall (35% of those under 30) gained campaign information from late-night talk shows such as “The David Letterman Show” and “The Tonight Show with Jay Leno” (Internet’s broader role, 2008). These media not only framed how viewers felt about the debates afterward, they also had a priming effect on how viewers would later see the debates and react to them. Holbert et al. (2007) showed this effect in the laboratory, where a sample of 371 students had significantly and predictably different ratings of the 2004 Bush-Kerry debates shortly after watching the politically charged movie, “Fahrenheit 9-11” compared to those who did not see the Michael Moore film. Survey data also indicated that President Bush suffered from the priming effect in his first 2004 debate with Sen. Kerry because it began minutes after news reports showed 35 Iraqi children slaughtered by car bombs that day (Rich, 2004). And priming appeared to hurt Sen. McCain in October 2008 when the Dow Jones stock average plummeted 500 points in the hours before his second debate with Sen. Obama (Briscoe, 2008). Given all of this history and research, the purpose of the current study is to begin to assess the pertinence of U.S. presidential debates in our 21st century world of media ubiquity. Are televised debates still unique and important means for voters to assess presidential candidates, learn about issues, and make up their mind whom to vote for—or are these debates 20th century anachronisms that are merely gist for other media and no longer the source of anyone’s decision making? Using the 2008 presidential debates as our case study and The 2008 Debates 14 anonymous surveys of citizens on both sides of the U.S.-Canada border, we pose the following research questions and hypotheses: RQ1: How will those who watch the 2008 presidential debates rate the candidates in comparison to those who don’t watch the debates and learn about them through the media? H1: The null hypothesis; there will be no significant differences between the debate watchers and non-watchers, because the media have primed most people and framed both candidates similarly. RQ2: How will Canadians rate the candidates in the 2008 U.S. presidential debates in comparison to U.S. Americans? H2: The null hypothesis; there will be no significant differences between the Canadians’ and Americans’ ratings, because U.S. media have primed U.S. and Canadian citizens and framed both candidates similarly in both countries. RQ3: How will those who listen to the presidential debates live with no video rate the candidates—immediately after the debate, before hearing any media commentary--compared to those who watch and listen to the debates? H3: The null hypothesis; there will be no significant differences between the debate watchers and listeners, because the media have primed most people in both groups similarly. RQ4: What set of debaters’ characteristics will have ratings most correlated with their “presidential” ratings? H4.1: The higher a debater’s “presidential” rating, the higher his overall debate performance will rate. H4.2: The higher a debater’s “presidential” rating, the more respondents will say they’d vote for him. The 2008 Debates 15 H4.3: Style characteristics will be more highly correlated than performance characteristics with debaters’ “presidential” ratings, because style trumps substance in televised debates. Methods We triangulated these research questions and hypotheses with an experiment, a survey of Canadians and Americans who watched one or more of the U.S. presidential debates, and a survey of Canadians and Americans who did not watch the televised debates. In the experiment, we surveyed participants immediately before they watched one of the televised debates live or listened to it live, without video—and we surveyed them again immediately after the telecast ended, before they heard or read any of the media’s post-debate analysis. This way, in particular, we could assess whether the “presidential” image is an artifact of television as opposed to radio, as was alleged after the Kennedy-Nixon debates, and we could eliminate the post-debate framing effect of the media. We could also somewhat control for the media’s pre-debate priming effect by surveying the participants for their biases immediately before the debate. To offset the somewhat-artificial, controlled aspect of this experiment, we also offered a parallel online survey for volunteers to fill out in the days after each presidential debate, whether they watched it live on television and/or learned about it later from the media. The experiment took place at a mid-size comprehensive university in the U.S. Midwest during the vice presidential debate and the first two presidential debates. We did not assess the third presidential debate, because viewership and interest historically decline for that debate. Also, by then, with the election fast approaching, media coverage is even more narrowly focused than usual on the “horse race” between the candidates. We opened the online survey to all students and staff/faculty at the same Midwestern university as where we conducted the experiment–and at an urban research university in eastern The 2008 Debates 16 Canada. We did not have the resources to conduct a random-sample survey across either nation, but we did assure that there was no prejudicial “ballot stuffing” of our online surveys by checking Internet Protocol addresses and eliminating any duplicate submissions. We did not hypothesize any significant difference in debater ratings based on the age or sex of the experiment or survey participants. Nearly all or them were students, many of whom professors had offered extra credit for their participation. The ratio of female participants to men reflected the predominantly female population of students at both universities. The lack of a random sample did not jeopardize our ability to test our hypotheses, and it is appropriate that this study of non-traditional media effects on presidential debates be dominated by participants who are young adults, because national surveys show they are heavy users of such media. Results This study had a total of 401 participants, 135 for the experiment and 266 respondents to the online surveys following the 2008 presidential and vice presidential debates. Of the survey respondents, 26% were in Canada and 74% in the United States. For the experiment and surveys altogether, 62% of the participants were women and 37% were men, with 1% not answering that. On cross tabulations between sex and all of the other variables in the study, the only one that reached statistical significance was regarding the “physical appearance” of the vice presidential debaters. Among men, 50.5% rated Republican nominee Sarah Palin’s looks a 9 or 10 on a 10point scale, compared to 33.3% of the women who rated her looks that high, p = .04. There were no significant differences, however, in the men’s and women’s ratings of Palin’s debate performance or the percentage of men and women who said they’d vote for the Republican ticket—before or after the vice presidential debate or either of the presidential debates. The 2008 Debates 17 Consistent with previous studies and national surveys, fewer than 2% of the participants in this study said the debate they responded to changed whom they favored for president. Also consistent with U.S. surveys of young adults, participants in this study leaned heavily toward the 2008 Democratic ticket—at the polls and in their assessment of who won each debate. Of the U.S. citizens, 80 percent said they intended to vote for Obama, 76 percent said he won his debates with McCain, and 81 percent said Sen. Joseph Biden won the vice presidential debate over Palin. Among Canadian respondents, 94 percent said they hoped Obama would win the White House, 97 percent said he won his debates, and 97 percent said Biden beat Palin, with the other 3 percent calling it a tie. Again, these data merely describe the participants in this study. We do not claim they are representative of the general population or even generalizable to college students across the United States and Canada. But this convenience sample was sufficient in size and variability to test our hypotheses on media effects on presidential debate audiences and to answer our research questions, at least on a tentative basis, as all research results are. Following, we’ll present the results for each hypothesis and research question: H1: There will be no significant differences between the debate watchers and nonwatchers, because the media have primed most people and framed both candidates similarly. The data support this hypothesis. Our online survey listed 17 ways that Americans or Canadians could primarily learn about the presidential debates, in addition to watching them live on TV. These means ranged from listening to the debates on broadcast or satellite radio, to seeing segments on satirical or talk TV shows, to reading about them in newspapers or blogs, to discussing them with friends or family on the phone or face-to-face. The majority, 60%, said they watched the debates live on TV, followed by 10% who read about them in online news sites The 2008 Debates 18 and 3% who watched parts of them on YouTube or other online video sites. Among the 160 online survey respondents who watched one of the presidential or vice presidential debate telecasts live and the 106 respondents who learned about the debates via other media, there were no statistically significant differences. Rather than a significant alpha of .05 or less, the levels of significance differences between the debate watchers and non-watchers were .36 as to who won the debate, .40 on who was more “presidential,” .50 on whom they favored for president after the debate, .54 on whom they said they favored going into the debate, .55 on McCain’s physical appearance, and .88 on Obama’s physical appearance. Thus, the answer to RQ1 is that those who didn’t watch the 2008 presidential debate telecasts got the same impression of the debates and the candidates as those who did watch the telecasts. H2: There will be no significant differences between the Canadians’ and Americans’ ratings, because U.S. media have primed U.S. and Canadian citizens and framed both candidates similarly in both countries. The data support this hypothesis. Among the 193 survey respondents in the United States and the 69 in Canada, there were no statistically significant differences in their debate ratings. Rather than a significant alpha of .05 or less, the levels of significance differences between those in the United States and those in Canada were .27 as to who won the debate, .52 on who was more “presidential,”.43 on McCain’s physical appearance, and .76 on Obama’s physical appearance. The only two variables for which there were significant differences were who they favored for president before the debate, p = .02, and after it, p = .003. In both cases, the respondents in Canada were even more heavily in favor of the Obama-Biden ticket than those in The 2008 Debates 19 the United States, as noted earlier, but this bias did not yield significant differences in how they rated the actual debate performances. Therefore, our answer to RQ2 is that Canadians responded to the 2008 presidential debates the same ways U.S. Americans did, even though they would not be able to vote in the election and even though they favored the Democratic ticket more heavily than their U.S. counterparts. This held true even though just 47.8% of the respondents in Canada watched the U.S. debates live (on cable TV; they were not on broadcast TV), compared to 64.8% of the U.S. Americans, p = .01. In other words, the data from our study indicate that respondents in Canada were affected by the priming and framing of the U.S. debates by the media in Canada—and the U.S. media available in Canada via the Internet, news wire services, cable TV, satellite TV, satellite radio, and broadcast signals bleeding across the border—in the same ways as U.S. respondents were. H3: There will be no significant differences between the debate watchers and listeners, because the media have primed most people in both groups similarly. The data support this hypothesis. Among the 72 experiment participants whom we surveyed immediately before and after they watched the vice presidential debate or one of the first two presidential debates and the 54 who listened to one of those debates without the video, there were no statistically significant differences in their overall ratings. Rather than a significant alpha of .05 or less, the levels of significance differences between those who watched the debates and those who listened without the video were .19 as to who won the debate, .62 on who was more “presidential,” .12 on whom they favored for president after the debate, .10 on whom they said they favored going into the debate, .80 on McCain’s physical appearance, and .26 on Obama’s physical appearance. The only statistically significant different ratings between The 2008 Debates 20 those who watched one of the debates and those who listened without the video resulted from the vice presidential debate. Although only nine of the 32 participants who watched that debate said Palin won it, none of the 20 audio-alone participants thought she bested Biden, p = .009. Similarly, the participants who watched that debate were significantly more impressed with Palin’s overall performance apart from Biden, with 35.1% rating her a 9 or 10 on a 10-point scale, compared to 4.3% of the audio-alone participants, p = .007. Neither of those differences remained significant when controlled for sex, despite the aforementioned men’s higher ratings for Palin’s physical appearance, but that could be due to the audio-alone group’s small N’s of 7 for men and 16 for women. Overall, our answer to RQ3 is that it makes no difference to audiences’ ratings of presidential debaters whether they watch the debate or listen to it without audio, with the possible minor exception of telegenic candidates such as Sarah Palin (and perhaps, by theoretical extension, John F. Kennedy). This is not because there’s no difference between the experiences of watching a presidential debate telecast and simply listening to it without any video but, we theorize, because those listening to the debate come into it having been exposed to the same media priming as those who watch the telecast, and they have already used all that information to make up their mind about the candidates, regardless of what happens during the debate. And in the days following, the media framing of what occurred during the debate brings the opinions of the debate watchers and non-watchers even more in concordance, as the answers to our first two research questions show. H4.1: The higher a debater’s “presidential” rating, the higher his overall debate performance will rate. The 2008 Debates 21 The data in this study support this hypothesis, replicating this finding from our study of the 2004 presidential debates (Dorsher, 2006). In both studies we simply asked each participant to rate how “presidential” each candidate seemed during the debate, on a scale of 1 to 10, without defining for them what “presidential” meant. As the previous hypotheses showed, there were no significant differences in the “presidential” ratings, whether a participant watched the debate or not, whether they watched it or listened to it without video, or whether they were in Canada or the United States. For this study of the 2008 debates, cross tabulations yielded a highly significant p < .001 for all 401 participants’ ratings of Obama’s or Biden’s “presidential” ratings and their overall debate performance, for McCain’s or Palin’s “presidential” ratings and their overall debate performance, for each ticket’s “presidential” ratings and the net winner of the debate, and for the net-most “presidential” candidate of each debate and the net winner of the debate. Taking the analysis a step further and treating these 110 ordinal ratings as interval data for a moment, linear regression of the 401 participants’ ratings of Obama’s and Biden’s “presidential” ratings onto their overall debate performance ratings yielded an R correlation of .75 with an adjusted R2 of .57, p < .001. Similarly, linear regression of McCain’s and Palin’s “presidential” ratings onto their overall debate performance ratings yielded an R of .80 and an adjusted R2 of .64, p < .001. H4.2: The higher a debater’s “presidential” rating, the more respondents will say they’d vote for him. The data support this hypothesis. For all 401 participants, the cross tabulation of which candidate was more “presidential” in each debate with which candidate they favor for president or vice president following the debate yielded a highly significant p < .001. Only 4.3% of those who favored Obama for president and Biden for vice president said that McCain or Palin were The 2008 Debates 22 more “presidential” in their debate. Conversely, though, nearly half of those who favored McCain and Palin for election after their debate--49.7%--acknowledged that Obama or Biden was more presidential in his debate performance. Also, the correlation between the netpresidential rating for each candidate and their post-debate support for the White House was .46, p =.01. H4.3: Style characteristics will be more highly correlated than performance characteristics with debaters’ “presidential” ratings, because style trumps substance in televised debates. The data support this hypothesis, although the search for a concise definition of what it means to be “presidential” remains elusive. We asked all of the participants in our study to rate each candidate first on how “presidential” they were in their debate but then also to rate them on 15 characteristics that we drew from the literature on presidential debates. These ranged from style characteristics such as “visionary” and “inspirational” to performance characteristics such as “intelligent” and “consensus-builder.” We hoped to narrow these 15 characteristics to a small number that highly correlated with the “presidential” rating for every candidate. That perspicuous solution did not immediately emerge, because among all 401 participants’ responses, nearly all 15 characteristics correlated with the “presidential” rating with significant (p < .01) but mild strength, in the range of .19 to .31. Factor analysis helped narrow the field, in addition to isolating the ratings from the vice presidential debate, which featured two candidates who were very different from each other—and from their running mates, in personal characteristics if not policy beliefs. Two factors emerged for both Obama and McCain. On one of the factors, the exact same two characteristics loaded for both candidates: “confident” and “determined,” so we consider them to be principal pieces of the “presidential” image. But they did not load on the same factor with the “presidential” variable itself. Two other characteristics The 2008 Debates 23 that did load heavily on both Obama’s and McCain’s primary factor, along with the “presidential” variable, were being “likable” and a “change agent.” A third characteristic that loaded heavily for McCain but not Obama was a being a “consensus-builder.” In the vice presidential debate, “change agent” and “consensus-builder” also loaded heavily with “presidential” for Biden and Palin, as did “confident” on the second factor for both. “Determined” also loaded heavily for Palin, as for McCain and Obama, but for Biden, “experienced” was the second-heaviest load on his second factor. In answer to RQ4, the “presidential” variable remains robust for predicting debate winners and election support, and that variable seems to primarily comprise style characteristics such as projecting confidence, determination, likability, and change, along with the ability to forge consensus. Discussion The purpose of this study was to build theory on how--and how much--U.S. presidential debates affect citizens in our 21st century hypermedia world. By extension, we are also studying what strategies presidential campaigns have—or could have—employed to optimize the effects of their debate performances on voters. Acknowledging first that no two debates or campaign cycles are exactly alike, we must conclude from the evidence in this study that the 2008 presidential debates did not have much direct effect on audiences. Certainly, the Obama campaign’s use of the Internet to communicate directly with voters and raise record-shattering totals from record-shattering numbers of contributors had a larger effect on the 2008 election than the debates, as did the world’s worst economic meltdown in four generations. As we hypothesized, participants in our study felt essentially the same about the debaters before and after the debates, whether they watched them or listened to them or tried to ignore The 2008 Debates 24 them, whether they were U.S. citizens or Canadians. Why? Why did these extraordinary opportunities to vicariously interview the next “leader of the free world” have such little effect? Because they are now swamped in a multimedia tsunami that primes and frames the debates so overwhelmingly that audiences cannot effectively see or hear or feel the original seismic event. When you’re drowning in the tidal wave, you care little about the epicenter, yet it was essential. We began with reference to The Racine Group’s 2002 white paper on debates research, and we’ll begin to end with it here. The Racine Group recommended four research questions: 1) How do debates achieve their effect? 2) What are the characteristics of the best campaign debates? 3) How can we optimize the potential of debates? 4) How can we best study debates? In this study, we have focused on the first question, and our answer foreshadows answers to the other questions. We conclude that presidential debates in the 21st century achieve their effect primarily through the media priming that precedes each debate and the media framing that follows it. If future studies replicate our research and generally confirm our results, the answers to The Racine Group’s second and third questions would have as much to do with the media as the debaters. Perhaps the answer is one The Racine Group apparently never considered: that televised presidential debates are an anachronism of the 20th century, and Americans should replace them with something(s) that better aid our judgments on election day. What that would be lies outside the bounds of this study, but we submit that most voters are already using media other than televised debates to make their ballot decisions. As to The Racine Group’s fourth question—How can we best study debates?—we start by acknowledging that this debates study falls short of the optimum. While our convenience sample of 401 mostly young adults was sufficient to test our hypotheses and tentatively answer our research questions, we agree with The Racine Group that researchers need more resources if The 2008 Debates 25 they are to continue studying presidential debates. They said “the two most compelling needs” were comprehensive records of media coverage of the debates and a longitudinal dataset of citizen responses to the debates (The Racine Group, 2002, pp. 215-216). By 2008, no one had fulfilled either of those needs, and the needs are expanding, based on our theory of the effects of media priming and framing on the debates. For the record of media coverage to be comprehensive, it would need to start with the first mention of an election year’s presidential debates and continue through election day. It would also need to include Internet social networks, blogs, video sites and mobile phone campaign messages and news in addition to a wider array of broadcast, cable, satellite, and print media. Similarly, the longitudinal dataset of citizen responses would need to start well in advance of the first debate and continue through election day, and ideally, these national random-sample surveys would need to track individual citizens’ array of media use much more broadly and minutely than ever before. Ultimately, we believe, research must shift to assessing experiments into a new generation of ways to scrutinize presidential candidates through our interactive new media. Conclusion Until well past their optimal usefulness, however, televised presidential debates are likely to continue. Nominees are likely to continue treating televised debates as minefields and imperatives to appear “presidential,” not as opportunities to win over voters with incisive ideas and disciplined leadership. The media are likely to continue treating debates as gunslinger showdowns and races to the finish, not as forums for the future and scrutiny of the world’s next supreme servant. As with everything else in the media and democracy, whether presidential debates continue to devolve into simulacrum or evolve into a new level of real discourse rests with us, the passive audience or the citizen participants. The 2008 Debates 26 References (2008). "CBS Poll: Obama boosted most by debate." Retrieved February 24, 2009, from http://www.cbsnews.com/stories/2008/09/27/politics/2008debates/main4482119.shtml?source=s earch_story. (2008). Debating the debates: They are unpredictable and often unfair, but there is no better test of a candidate. Economist. 389. (2008, January 11). "Internet's broader role in campaign 2008: Social networking and online videos take off." Retrieved March 6, 2009, from http://people-press.org/report/384/internets-broader-role-incampaign-2008. Benoit, W. L. and A. Harthcock (1999). "Functions of the great debates: acclaims, attacks, and defenses in the 1960 presidential debates." Communication Monographs 66(4): 341-358. Blais, A. and M. M. Boyer (1996). "Assessing the impact of televised debates: the case of the 1988 Canadian election." British Journal of Political Science 26(2): 143-164. Blais, A. and A. M. L. Perrella (2008). "Systemic effects of televised candidates' debates." The International Journal of Press/Politics 13(4). Briscoe, D., E. Clift, et al. (2008). The great debates. Newsweek. New York, The Washington Post Col. 152: 10. Chong, D. and J. N. Druckman (2007). "Framing theory." Annual Review of Political Science 10(1146): 103-126. Dorsher, M. (2006). Is seeing--or hearing--believing? Responses to the 2004 presidential debates. Association for Education in Journalism and Mass Communication. San Francisco, CA. Druckman, J. N. (2003). The power of television images: the first Kennedy-Nixon debate revisited. The Journal of Politics, 65(2 (May)), 559-571. The 2008 Debates 27 Hart, R. P. (1982). "A commentary on popular assumptions about political communication." Human Communication Research 8: 366-389. Holbert, R. L., G. J. Hansen, et al. (2007). "Presidential debate viewing and Michael Moore's "Fahrenheit 9-11": a study of affect-as-transfer and passionate reasoning." Media Psychology 9: 673-694. Jamieson, K. H., & Birdsell, D. S. (1988). Presidential debates: the challenge of creating an informed electorate. New York: Oxford University Press. Jones, K. T. (2005). The role of televised debates in the U.S. presidential election process, 1960-2004. New Orleans, LA, University Press of the South. Kraus, S., Ed. (1962). The great debates: Kennedy vs. Nixon, 1960. Bloomington, IN, Indiana University Press. Lang, G. E. and K. Lang (1979). Immediate and mediated responses: first debate. The great debates: Carter vs. Ford, 1976. S. Kraus. Bloomington, IN, Indiana University Press. Lanoue, D. J. (1991). "Debates that mattered: voters' reaction to the 1984 Canadian leadership debates." Canadian Journal of Political Science 24(1): 51-65. Lanoue, D. J. and P. R. Schrott (1991). The joint press conference: the history, impact, and prospects of American presidential debates. New York, Greenwood Press. Lemert, J. B., W. R. Elliott, et al. (1996). The politics of disenchantment: Bush, Clinton, Perot and the press. Cresskill, NJ, Hampton Press. Leroux, C. (1992). Open to debate: analysts, not candidates, often decide winner. Chicago Tribune. Chicago: 1. Luo, M. (2008). Obama recasts the fund-raising landscape. The New York Times. New York: A21. Martel, M. (1983). Political campaign debates: images, strategies, and tactics. New York, Longman. The 2008 Debates 28 Miller, A. H., M. P. Wattenberg, et al. (1986). "Schematic assessments of presidential candidates." American Political Science Review 80: 521-540. Moniere, D. (1988). Le discours electoral: Les politiciens sont-ils fiables? Quebec, QC, Editions Quebec/Amerique. Nixon, R. M. (1962). Six crises. Garden City, NY, Doubleday. Patterson, T. E. (1980). The mass media election: How Americans choose their president. New York, Praeger. Pfau, M. (2002). "The subtle nature of presidential debate influence." Argumentation and Advocacy 38: 251-261. Racine Group, T. (2002). "White paper on televised political campaign debates." Argumentation and Advocacy 38: 199-218. Ragazzini, G., D. R. Miller, et al. (1985). Campaign language: language, image, myth in the U.S. presidential election 1984. Bologna, Italy, Editrice. Rich, F. (2004). Why did James Baker turn Bush into Nixon? The New York Times. New York: 2.1. Richardson, J. D., W. P. Huddy, et al. (2008). "The hostile media effect, biased assimilation, and perceptions of a presidential debate." Journal of Applied Social Psychology 38(5): 1255-1270. Schroeder, A. (2008). Presidential debates: fifty years of high-risk TV. New York, Columbia University Press. Sears, D. and S. Chaffee (1979). Uses and effects of the 1976 debates: an overview of empirical studies. The great debates: Carter vs. Ford, 1976. S. Kraus. Bloomington, IN, Indiana University Press. Shapiro, W. (1992). What debates don't tell us. Time. 140: 32. Smith, C. and B. Voth (2002). "The role of humor in political argument: how "strategery" and "lockboxes" changed a political campaign." Argumentation and Advocacy 39: 110-129. The 2008 Debates Steeper, F. T. (1978). Public response to Gerald Ford's statements on Eastern Europe in the second debate. Presidential debates: media, electoral, and policy perspectives. G. F. Bishop, R. G. Meadow and M. Jackson-Beeck. New York, Praeger. Trent, J. and R. V. Friedenberg (2004). Political campaign communication. New York, Praeger. Tuchman, G. (1978). Making news. New York, Free. 29