Black status @ 1950 (no pics).doc - Northcote

advertisement

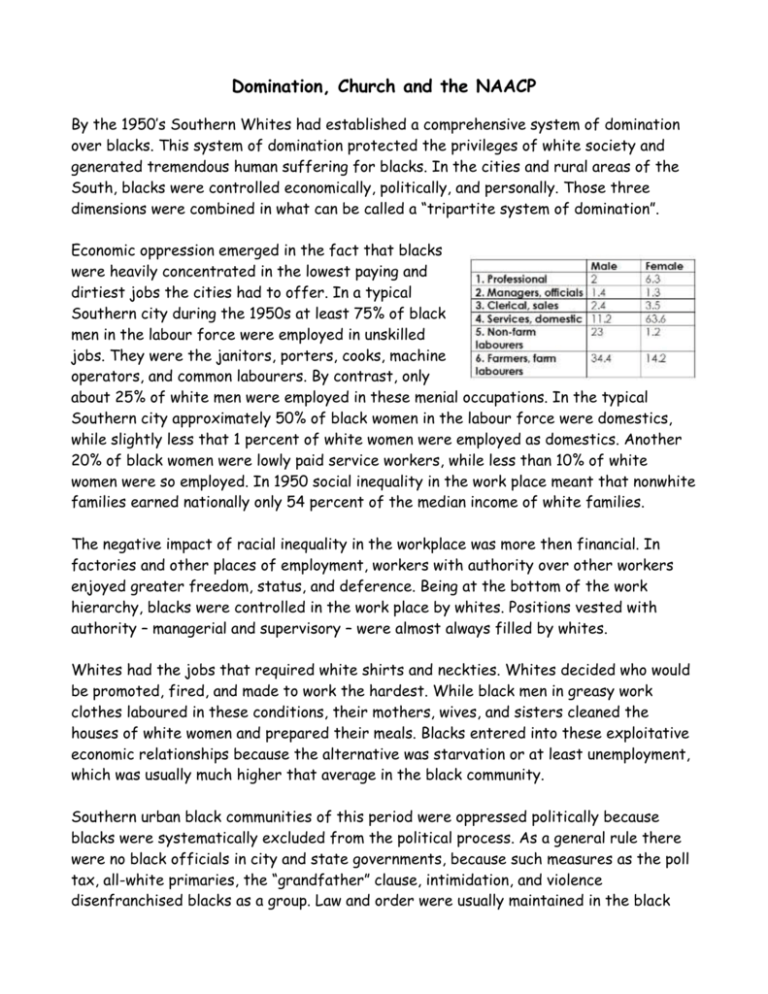

Domination, Church and the NAACP By the 1950’s Southern Whites had established a comprehensive system of domination over blacks. This system of domination protected the privileges of white society and generated tremendous human suffering for blacks. In the cities and rural areas of the South, blacks were controlled economically, politically, and personally. Those three dimensions were combined in what can be called a “tripartite system of domination”. Economic oppression emerged in the fact that blacks were heavily concentrated in the lowest paying and dirtiest jobs the cities had to offer. In a typical Southern city during the 1950s at least 75% of black men in the labour force were employed in unskilled jobs. They were the janitors, porters, cooks, machine operators, and common labourers. By contrast, only about 25% of white men were employed in these menial occupations. In the typical Southern city approximately 50% of black women in the labour force were domestics, while slightly less that 1 percent of white women were employed as domestics. Another 20% of black women were lowly paid service workers, while less than 10% of white women were so employed. In 1950 social inequality in the work place meant that nonwhite families earned nationally only 54 percent of the median income of white families. The negative impact of racial inequality in the workplace was more then financial. In factories and other places of employment, workers with authority over other workers enjoyed greater freedom, status, and deference. Being at the bottom of the work hierarchy, blacks were controlled in the work place by whites. Positions vested with authority – managerial and supervisory – were almost always filled by whites. Whites had the jobs that required white shirts and neckties. Whites decided who would be promoted, fired, and made to work the hardest. While black men in greasy work clothes laboured in these conditions, their mothers, wives, and sisters cleaned the houses of white women and prepared their meals. Blacks entered into these exploitative economic relationships because the alternative was starvation or at least unemployment, which was usually much higher that average in the black community. Southern urban black communities of this period were oppressed politically because blacks were systematically excluded from the political process. As a general rule there were no black officials in city and state governments, because such measures as the poll tax, all-white primaries, the “grandfather” clause, intimidation, and violence disenfranchised blacks as a group. Law and order were usually maintained in the black community by white police forces. It was common for law officials to use terror and brutality against blacks. Due process of law was virtually nonexistent because the courts were controlled by white judges and juries, which routinely decided in favour of whites. The white power structure made the decisions about how the public resources of the cities were to be divided. Blacks received far less than whites, because in practice blacks had few citizenship rights and were not members of the polity. Compounding the economic and political oppression was the system of segregation that denied blacks personal freedoms routinely enjoyed by whites. Segregation was an arrangement that set blacks off from the rest of humanity and labeled then as an inferior race. Blacks were forced to use different toilets, drinking fountains, waiting rooms, parks, schools, and the like. These separate facilities forever reminded blacks of their low status by their wretched condition, which contrasted sharply with the wellkept facilities reserved for whites only. The “coloured” and “white only” signs that dotted the buildings and public places of a typical Southern city expressed the reality of a social system committed to the subjugation of blacks and the denial of their human dignity and self-respect. Segregation meant more than separation. To a considerable extent it determined behaviour between the races. Blacks had to address whites in a tone that conveyed respect and use formal titles. Sexual relationships between black men and white women were viewed as the ultimate infraction against the system of segregation. Black males were therefore advised to stare downward when passing a white woman so that she would have no excuse to accuse him of rape and have his life snatched away. Indeed segregation was a personal form of oppression that severely restricted the physical movement, behavioural choices, and experiences of the individual. The tripartite system of racial domination – economic, political, and personal oppression – was backed by legislation and the iron fist of Southern governments. In the short run all members of the white group had a stake in racial domination, because they derived privileges from it. Poor and middle-class whites benefited because the segregated labour force prevented blacks from competing with them for better paying jobs. The Southern white ruling class benefited because blacks supplied them with cheap labour and a weapon against the labour movement, the threat to use unemployed blacks as strikebreakers in labour disputes. Finally, most Southern whites benefited psychologically from the system’s implicit assurance that no matter how poor or uneducated, they were always better than the niggers. Meager incomes and the laws of segregation restricted city blacks to slum neighbourhoods. In the black part of town housing was substandard, usually dilapidated, and extremely overcrowded. The black children of the Southern ghetto received fewer years of formal schooling than white children, and what they did receive was usually of poorer quality. On the black side of town life expectancy was lower because of poor sanitary conditions and too little income to pay for essential medical services. Adverse social conditions also gave rise to a “black-against-black” crime problem, which flourished, in part, because its elimination was not a high priority of the usually all-white police forces. Ironically, urban segregation in the South had some positive consequences. It facilitated the development of black institutions and the building of close-knit communities when blacks, irrespective of education and income, were forced to live in close proximity and frequent the same social institutions. Maids and janitors came into close contact with clergy, schoolteachers, lawyers, and doctors. In the typical Southern city, the black professional stratum constituted only about 3 percent of the black community. Skin colour alone, not class background or gender, locked blacks inside their segregated communities. Thus segregation itself ensured that the diverse skills and talents of individuals at all income and educational levels were concentrated within the black community. Cooperation between the various black strata was an important collective resource for survival. Segregation provided the constraining yet nurturing environment out of which a complex urban black society developed. The influx of migrants from rural areas intensified the process of institution-building. The heavy concentration of blacks in small areas in the cities engendered efficient communication networks. In cities, white domination was not as direct as on the plantations, because urbanization tended to foster impersonal, formal relationships between the races. Within these compact segregated communities blacks began to sense their collective predicament as well as their collective strength. Growth in the black colleges and in the black church was especially pronounced. It was the church more than any other institution that provided an escape from the harsh realities associated with domination. Inside its wall blacks were temporarily free to forget oppression while singing, listening, praying, and shouting. The church also provided an institutional setting where oppression could be openly discussed and resources could be developed to organize collective resistance. By the 1950s the tripartite system of domination was firmly entrenched in Southern cities, but in those cities were born the social forces that would challenge the very foundations of Jim Crow.