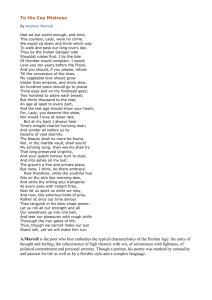

Andrew Marvell: “To His Coy Mistress”

advertisement

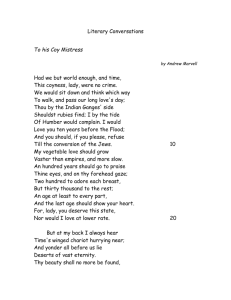

Andrew Marvell: “To His Coy Mistress” About the Selection: Marvell’s work has been called “the most major minor verse in English,” and this poem in particular shows why so many readers enjoy Marvell. Rich in sensory images and flattery, “To His Coy Mistress” is designed to appeal to feelings as well as to the intellect. Its exaggerated emotion and its persuasive tone are humorous to readers who recognize the speaker’s goal. Background: By the seventeenth century, the English language has become a fluid combination of Anglo-Saxon, Gaelic, Latin, and French. It was more than a tool for basic communication. Through it, one could express philosophical ideas, convey abstract theories, and indulge in humorous wordplay. These poems show the range of this language, from witty puns to fanciful imagery. The carpe diem theme is not confined to the seventeenth century England. It can be found among the writings of different cultures and different times. For example, in 24 B.C., the Egyptian Ptahhotpe wrote, “The wasting of time is an abomination to the spirit.” The Persian poet Omar Khayya, noted the passage of time in The Rubaiyat. Before reading the poem: Notes on the selection: Humber- river flowing through Hill, Marvell’s home town Conversation of the Jews- according to Christian tradition, the Jews were to be converted immediately before the Last Judgment State- dignity Coyness- shyness; aloofness, often as part of flirtation Transpires- breathes out Slow-chapped- slow-jawed Thorough- through Amorous- full of love or desire Languish- to become weak To His Coy Mistress by Andrew Marvell Had we but world enough, and time, This coyness, lady, were no crime. We would sit down and think which way To walk, and pass our long love's day; Thou by the Indian Ganges' side Shouldst rubies find; I by the tide Of Humber would complain. I would Love you ten years before the Flood; And you should, if you please, refuse Till the conversion of the Jews. My vegetable love should grow Vaster than empires, and more slow. An hundred years should go to praise Thine eyes, and on thy forehead gaze; Two hundred to adore each breast, But thirty thousand to the rest; An age at least to every part, And the last age should show your heart. For, lady, you deserve this state, Nor would I love at lower rate. But at my back I always hear Time's winged chariot hurrying near; And yonder all before us lie Deserts of vast eternity. Thy beauty shall no more be found, Nor, in thy marble vault, shall sound My echoing song; then worms shall try That long preserv'd virginity, And your quaint honour turn to dust, And into ashes all my lust. The grave's a fine and private place, But none I think do there embrace. Now therefore, while the youthful hue Sits on thy skin like morning dew, And while thy willing soul transpires At every pore with instant fires, Now let us sport us while we may; And now, like am'rous birds of prey, Rather at once our time devour, Than languish in his slow-chapp'd power. Let us roll all our strength, and all Our sweetness, up into one ball; And tear our pleasures with rough strife Thorough the iron gates of life. Thus, though we cannot make our sun Stand still, yet we will make him run. Questions related to the selection: 1. Read aloud the first two lines. How do these lines express the theme of carpe diem? 2. What are the speaker’s feelings for the women? What is the speaker’s frame of mind? ( see lines 1-17) 3. What is the lady’s crime? 4. Rephrase the last six lines of the poem into your own words: 5. What new twist does the speaker apply in order to “solve” the problem of fleeting time? Let’s Look Deeper: 6. If you were the lady, how would you respond to the speaker? Why? 7. Name three things the speaker and his mistress would do and the time each would take if time were not an issue. How do these images relate to the charge the speaker makes against his lady in lines 1-2? 8. Why would the speaker be willing to spend so much time waiting for his mistress? 9. What future does the speaker foresee for himself and his love in lines 25-30? How do the images in lines 21-30 answer the images in the first part of the poem? 10.Why does the speaker save the urgent requests in line 33-46 for the end? Writing Exercise: Is Marvell’s idea of love realistic or idealistic? Explain.